Hedge Funds Say There’s No Turning Back on Abe’s Japan Reforms

Hedge Funds believe that this reform by Shinzo Abe is here to stay.

(Bloomberg) -- It started with little fanfare, the series of reforms of Japanese corporate governance that would become one of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s biggest legacies.

Then it built and built. During the more than 7 1/2 years of his second spell in office, Japan Inc. changed notably, becoming more profitable, less insular and more rewarding as investments.

For the hedge funds that bet on Japanese firms throughout the period, and pressed them to change, there’s no chance the work that Abe started will be derailed even after he steps down. The genie is out of the bottle, they say, and it can’t be put back in. That’s especially true if, as expected, Abe’s successor continues with his program.

“The impact of these policies on corporate behavior in Japan cannot be overstated,” said Seth Fischer, chief investment officer of Oasis Management Co., a Hong Kong-based hedge fund that’s been at the forefront of activist investing in Japan under Abe. “These changes are here to stay.”

Abe’s administration introduced a stewardship code in 2014, seeking to enlist Japan’s often hands-off institutional investors to press companies to improve profitability and capital efficiency. The following year, it created the corporate governance code, a complementary set of rules for companies to follow.

Neither code was mandatory, and some questioned whether the voluntary rules would have an effect.

But one data point shows that companies took them seriously. In 2012, the year Abe came to power, just 27% of firms in the benchmark Topix index of stocks had two or more outside directors. By 2019, some years after having independent directors became called for in the corporate governance code, the proportion had risen to 97%, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

“There’s been a real profound change in how Japanese boards work, and that’s very much down to the reforms initiated by Abe,” said George Olcott, a guest professor at Keio University who has served as an outside director at several Japanese companies since 2008.

At the same time, profit margins at Topix firms were higher at the end of 2019 compared to the end of 2012. Return on equity, a measure of profit from shareholder funds, also climbed in the period, although it remains below the level of companies in the U.S. benchmark gauge. And returns to stock owners in the form of dividends and buybacks increased to a record in the fiscal year ended March, according to Jefferies.

“A view that corporate managers are responsible for delivering good results while appropriately governing themselves has taken firm hold,” said Atsushi Akaike, co-head of Japan at private equity firm CVC Capital Partners Ltd. “That means a lot.”

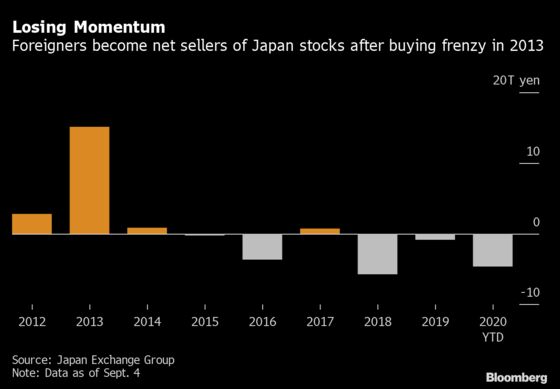

An investment in the Topix on the day Abe returned to power would be worth more than 90% more today. But since piling into the nation’s equities on Abe optimism in 2013, foreign investors have been net sellers of Japanese stocks.

While heralding the corporate governance overhaul, analysts also point to areas where the prime minister was less successful.

For Nobuko Kobayashi, a partner at Ernst & Young in Tokyo, Abe could have done more to increase wages at Japanese firms, which would have helped spur inflation. He also fell short in his efforts to appoint more women to managerial roles, she said. In July, Japan postponed its goal of getting women into 30% of the nation’s leadership positions by 2020.

“The structural reform part of Abenomics is only 20% or 30% done,” said Nicholas Benes, head of the Board Director Training Institute of Japan, referring to Abe’s three-pronged policy program that also included aggressive monetary easing and fiscal stimulus. Japan needs to do more to reform its inflexible labor market and to increase immigration given its aging and shrinking population, he said.

“Diversity still has a way more narrow meaning in Japan,” said Olcott. “Although Abe has been called a much more global prime minister than his predecessors, Japanese companies are way short of being global in the way European and North American companies are.”

Whoever takes the prime minister job is set for a massive task after the coronavirus pandemic sent the economy to its worst contraction on record when it fell an annualized 27.8% in the three months through June from the previous quarter. Yoshihide Suga, Abe’s right-hand man, is all but assured of succeeding him, and says he’ll maintain the direction of Abe’s policies.

But Jamie Rosenwald, the co-founder of Dalton Investments, a $2.9 billion U.S. money manager that actively invests in Japanese stocks, says Abe’s corporate governance overhaul couldn’t be reversed no matter who gets the job.

“One always is concerned by a reversal in reform movements when the leader steps aside,” Rosenwald said. But “we are long past the point of no return. Independent directors on corporate boards will continue the work that Abe-san initiated.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.