Hedge Fund Giants Lose Their Appeal as Havens in Global Turmoil

Investors have thronged the largest hedge funds since the last financial crisis as they sought safety in size.

(Bloomberg) -- Investors have thronged the largest hedge funds since the last financial crisis as they sought safety in size. Now, they’re paying a hefty price.

Supersized funds are failing their clients during a period of market upheaval that in theory should pose an unprecedented chance to make money. Instead of profiting, though, some of the world’s biggest hedge funds have barely managed to protect their investors from losses.

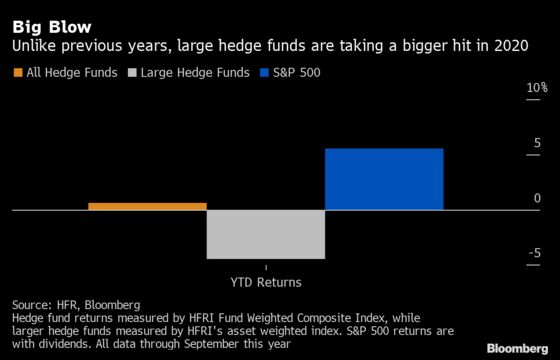

A Hedge Fund Research gauge that gives more weight to larger players was down 4.4% this year through September, while all hedge funds on average managed to eke out a small profit. Gold-plated names that have slumped include Bridgewater Associates, quant powerhouses Renaissance Technologies and Winton, Michael Hintze’s CQS and Lansdowne Partners.

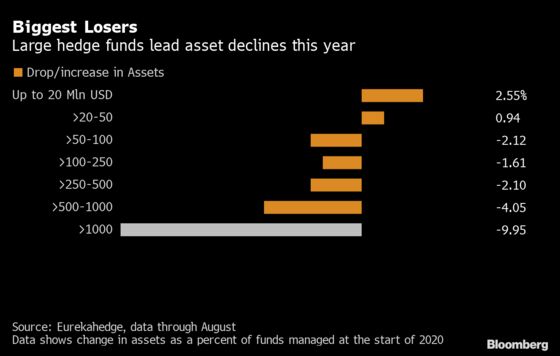

The losses are largely hurting influential institutional investors -- pension funds, insurers and endowments -- that contribute most to the industry’s assets and back the biggest funds. A reckoning looms as clients accelerate their flight. Investors pulled $89 billion from hedge funds in the first nine months of the year, mainly from large firms, according to Eurekahedge data.

“A very large portion of the assets invested in large hedge funds have not performed all that well and so it’s causing investors to reassess their objectives,” said Chris Walvoord, global head of hedge fund research at investment consultant Aon Plc. They’re asking, “Why am I invested in this? What’s the purpose?”

Larger hedge funds have traditionally been seen as more stable in down markets, a perception borne out in performance data going back more than a decade. Big funds lost less than their smaller counterparts nearly two-thirds of the time since the global financial crisis, according to an analysis of every loss-making month from 2008 to 2019. But that pattern broke down in 2020.

Hedge funds with more than $1 billion in assets racked up about $60 billion in performance losses this year through September, or just over 5% of their capital, according to Eurekahedge. Investors would have done far better with an index fund tracking the stock market: the S&P 500 rose 5.6%.

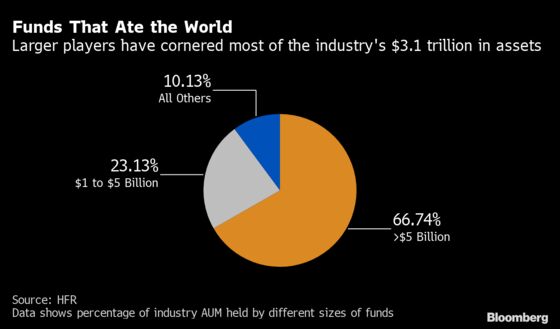

The supersizing of hedge funds evolved as institutions gradually replaced wealthy individuals as their biggest clients. Since most of those investors lack inhouse research teams and need to allocate hundreds of millions of dollars to have any meaningful impact on their portfolios, they’ve tended to park money with the largest, well-known hedge funds.

This has led to larger funds gobbling up fresh capital and smaller ones running out of business. Of a net $170 billion poured into hedge funds since 2010, some $135 billion has gone into larger ones, according to HFR data.

Size has become a burden. The sheer scale of some funds makes it harder for them to react by switching in and out of bets. So when volatility roiled stocks, bonds, currencies and commodities earlier this year, a large number of giant players lost record amounts of money.

The eight months through August were ugly: Bridgewater Associates’ flagship fund lost 18.6%; Renaissance Institutional Equities was down 13%; Winton’s main fund slumped about 19%; Hintze’s CQS hedge funds fell 42.5%; while Lansdowne Developed Markets Fund was down almost 22%.

With the U.S. election around the corner and a raging pandemic still causing havoc across continents, there’s little sign that the volatility that bled hedge funds is on the wane.

“Market fragility remains elevated and speed is also high, meaning sharper but shorter duration moves are more likely to occur,” said Adam Jones, a partner at investment advisory firm Albert E Sharp.

Even before the pandemic, investors were questioning the high fees charged by hedge funds for mediocre returns. Until now, many got away by blaming the lack of volatility for their woes -- so 2020 should have potentially provided their best trading opportunity in years.

Not all large hedge funds have disappointed. Multi-strategy firms such as Citadel, Balyasny Asset Management and Millennium Management, which rely on dozens of traders to generate profits, are having one of their best years. Such funds are typically dominated by trading-oriented strategies and volatility tends to create more opportunities for them.

Doing the Math |

|---|

PivotalPath, a technology-driven hedge fund consultant that covers $2.3 trillion in assets, recently quantified the extent of underperformance by larger players:

|

Some macro hedge funds run by the likes of Brevan Howard Asset Management, Rokos Capital and Caxton Associates have also churned out bumper profits. But they hide a truer picture of an industry which continues to struggle.

One reason why smaller funds are doing better is that they’re jumping on very niche trading opportunities that just don’t have capacity for the billions of dollars their larger peers need to invest.

“The irony is that the hedge fund industry was built on investing with small, nimble managers who could exploit esoteric investment opportunities,” said Andrew Beer, founder of New York-based Dynamic Beta investments. “The last several years have shown that sometimes big might be too big, especially when fees consume most performance.”

From the archive: Hedge-Fund Swagger Sinks Along With Profits and Fees: QuickTake

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.