Goldman Sees a Bargain in Japan Cram School With Checkered Past

Goldman Sees a Bargain in Japan Cram School With Checkered Past

(Bloomberg) -- Noriko Mori, 47, paid about 700,000 yen ($6,300) to a cram school to help her daughter prepare for a school entrance exam in Tokyo. Her daughter was six at the time. It was for an elementary school.

“It was expensive,” Mori said. But “she passed the test for the school she wanted, so it was a choice well made.”

The cram school in question was Riso Kyoiku Co., which provides private lessons to children of all ages whose parents can afford to pay. Goldman Sachs Group Inc. thinks it’s a winning strategy, and has initiated coverage on the stock.

For parents like Mori, this is just the start of a years-long journey toward ultimately getting their children into one of Japan’s top universities. For a medical school, Riso offers courses that cost 3 million yen to 4 million yen a year. On average, their courses cost 1.2 million yen to 1.5 million yen annually.

In a society where more women are working, the courses are in high demand. And the fact that they have fewer children means they have more money to spend on them. Through its flagship program called Tomas, which provides only one-on-one tutoring, Riso has been capturing the education fever among wealthier Japanese that’s also seen in countries like China and South Korea.

“More people are able to pay for good education -- we’re riding that trend,” Mitsugu Iwasa, Riso Kyoiku’s founder, who’s now an adviser to the company, said in an interview in Tokyo. “There’s a deep-rooted culture in Japan that it’s fine even if it’s expensive as long as it allows you to get into the school you want.”

Goldman Sachs initiated coverage of Riso Kyoiku in December with a buy rating, saying the company is “benefiting from the demand shift from group to individual tutoring.” Despite a decline in the number of students, the market for preparatory schools providing individual tutoring expanded from 374 billion yen in revenue to an estimated 442 billion yen in 2018, the brokerage said, citing Yano Research Institute Ltd.

“We expect education spend per child to continue increasing in line with the trend toward fewer children per household,” Goldman analyst Yukiko Nonami wrote in a note. The “growth potential of the early childhood education business is not adequately priced into the shares.”

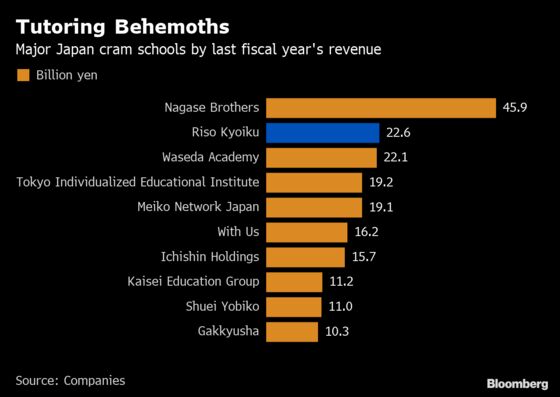

The stock surged to its highest in almost 14 years in January, before paring some of its gains. It still trades at 41 times estimated earnings, a multiple more than three times higher than the average for companies in the Topix index. Its peer Waseda Academy Co. trades at 18 times expected profits, while Meiko Network Japan Co. trades at 28 times.

Riso Kyoiku is recovering after an accounting scandal that dealt a blow to its reputation. In 2014, the company was found to have inflated sales over a period of many years. In February that year, the president of the company and two other executives resigned.

“The damage was huge,” Iwasa recalled. “We adopted very strict compliance rules. I now think there were things we gained from the experience. We became stronger.”

Riso posted a 34 percent year-on-year increase in operating profit to 1.5 billion yen for the nine-month period ended November. Goldman forecast the company’s operating profit will grow at an annual pace of 23 percent for the next five years, as demand for individual tutoring grows and Riso expands into daycare services that will serve as new growth drivers.

Iwasa prides himself on pioneering the industry of one-on-one private tutoring and is confident this business model is sustainable. Riso started in 1985 with a model like those of its peers, where groups of students learned from the same teacher. But by the 1990s the cram school industry was saturated amid a declining birthrate.

“I thought about what we’d have to do to survive,” said Iwasa, who estimates roughly 70 percent to 80 percent of cram schools from the 1990s have disappeared. “China gave me a hint.”

China then had fostered a culture of concentrating a family’s wealth into a single child. Iwasa thought a similar approach could be applied to Japan’s private schooling system.

“We narrowed our target,” Iwasa said. “We’d provide thorough preparation for each student in getting into the school they want. But it would be expensive.”

Riso built its reputation by helping to get students into a number of prestige universities. The method has grown so popular that it has caught the attention of schools. While cram schools and the public education system have long had a fraught relationship, schools in Japan are now looking for ways to differentiate themselves. One of those ways was to form partnerships with Riso Kyoiku to provide their tutoring services on school premises.

That was the start of what Riso calls “School Tomas,” dispatching tutors to schools such as Nishiyamato Gakuen, a middle and high school located in Nara prefecture. The company has partnered with 40 schools so far, and aims to increase this to 70 over the next year.

Riso operates about 80 branches for Tomas, which account for almost half of the company’s sales. A service for dispatching tutors to households accounts for about one-fifth, and a service for pre-school children accounts for another fifth. School Tomas makes up about six percent.

Iwasa has no overseas ambitions, because he sees enough room for growth in Japan. Riso aims to boost annual revenue by more than 20 percent to 30 billion yen in two years from an estimated 24.7 billion yen for the year ending February, he said.

“We’re just starting to bloom,” Iwasa said.

--With assistance from Ma Jie.

To contact the reporters on this story: Min Jeong Lee in Tokyo at mlee754@bloomberg.net;Ayaka Maki in Tokyo at amaki8@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Divya Balji at dbalji1@bloomberg.net, Tom Redmond

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.