Italy’s Broken Finances Bring Back Fears of Messy Euro Divorce

Ghost of 1992 Italy Devaluation Returns to Haunt Euro Unity Aims

(Bloomberg) -- On the September night in 1992 when George Soros famously broke the Bank of England, it wasn’t just the British pound that crashed. The Italian lira cratered too, the last of its numerous 20th century devaluations.

One veteran who is still at the Finance Ministry in Rome recalls a colleague researching “bankruptcy” and “failed state” amid the chaos as resentment swelled at the indifference of European allies, notably Germany.

Those memories of market mayhem re-emerged along with the old fault lines following the economic shock of the coronavirus lockdowns. Italy did make it to the monetary mainstream, becoming a founding euro member, but the mutual recriminations were never far from the surface — nor were doubts from skeptics like the billionaire Soros and Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz that it was just a matter of time before the imperfect union of diverging economies would eventually fall apart.

While betting on a euro breakup has proved to be a long-term loser, Italy’s tattered finances have pushed the question back to the top of mind for investors in Europe. If nothing else, the prospect of the black swan rising is sure to stoke sudden market eruptions, which could also provide occasional opportunity: in 2013, with Grexit on the table, Greek bonds returned almost 50%.

“There are only two options: either the union is drawing further together over time or it will fall apart,” says Mark Dowding, chief investment officer of BlueBay Asset Management. He added Italian debt last month, expecting that the buyers of last resort at the European Central Bank will give political leaders enough time and space to figure it out.

The ECB has enabled Italy to keep servicing its giant 2.4 trillion-euro ($2.6 trillion) debt load affordably. While the cost of insuring against default rose in March to its highest since 2013, 10-year bonds still yield less than 2%. In 2011, they topped 7%. The government tapped the market again Wednesday, selling 9 billion euros in bonds.

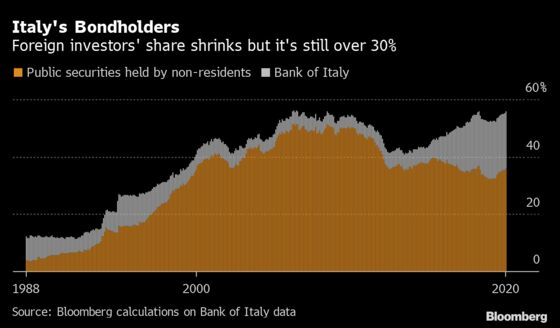

Another difference from 2011 is that the politics are much more complicated. Unlike Greece, Italy has meaningful leverage: foreign investors hold more than 700 billion euros of its bonds, a third of the total, according to Bank of Italy data. Any problem there would be enough to send shock waves through global financial markets and Europe’s weakened banking system.

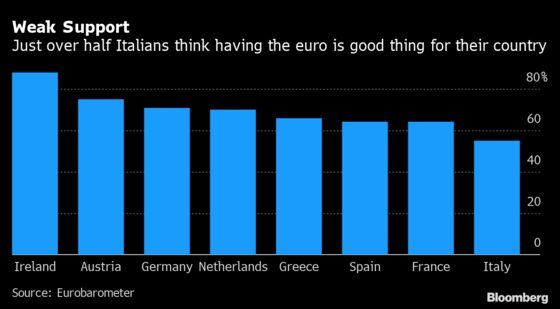

No one in Rome needed to hear the warning last week from the European Commission that the virus-spawned recession will be severe enough to put euro unity at risk. Like his forebears in 1992, Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte felt abandoned by his allies early on in the pandemic when France and Germany ignored Italy’s cries for help. Italian opposition leader Matteo Salvini expresses sympathy for fans of a referendum on exiting that would tap into rising Italian frustration with the euro.

The wrangling was on display last week when euro-area finance chiefs approved a deal to provide ultra-cheap loans via its rescue fund, but without any onerous conditions. Yet the insistence by Italy’s populist opposition that such loans would undercut the country’s sovereignty has rendered them politically toxic — even if they would lead to greater savings. Along with France and Spain, Italy has been pushing the bloc for joint borrowing against opposition from the likes of Germany, the Netherlands and Austria.

Austrian Chancellor Sebastian Kurz fired a volley on Tuesday when he told Italy to appreciate the help on offer. “They wouldn’t be able to handle this situation without the help of the EU and countries like Austria,” the 33-year-old chancellor said in a Bloomberg TV interview.

German judges threw up the latest hurdles this month, questioning the legality of the ECB’s bond buying, a legacy bequeathed by Mario Draghi, a former Bank of Italy chief who steered the ECB into unprecedented activism during the crises spawned by Greece.

“Fault lines are showing again, old vulnerabilities are emerging,” said Stewart Robertson, senior economist at Aviva Plc. “In a crisis, the ECB has been the backstop for European integration, to guarantee survival of the eurozone. We see once again the ECB do the heavy lifting.”

Draghi was initially welcomed by the Germans. The nation’s most widely read newspaper, Bild Zeitung, presented him with a 19th century spiked Prussian military helmet in early 2012, calling him an honorary German. Not long after, came the backlash. The tabloid called his plan to shore up the euro by buying bonds a “black day” for the currency.

“There has been a secret romanization of European monetary policy,” but German conservatives have drawn a red line at fiscal policy, Adam Tooze, economic historian at Columbia University, now says.

Even without the German decision on the ECB, the risks of buying Italian debt were too great, said Patrice Gautry, an economist at Union Bancaire Privee, as he mused on worst-case outcomes. “A bold option would be for Italy and other Club Med countries to split from the euro zone, with different, looser rules on the debt side,” he says. “It was something already discussed with the Greek crisis.”

Nicola Mai, a money manager at bond powerhouse Pacific Investment Management Co., says history is on the union’s side. He has enough confidence to own more Italian debt than benchmarks — overweight, in the jargon of the trade. “Whenever there is a crisis, the euro area responds late because it needs to see the pain before it delivers. But eventually it gets there,” he said.

Still, “medium-term integrity risks for the eurozone remain in place,” he says. “You cannot exclude that something goes wrong, even though it’s not our base case.”

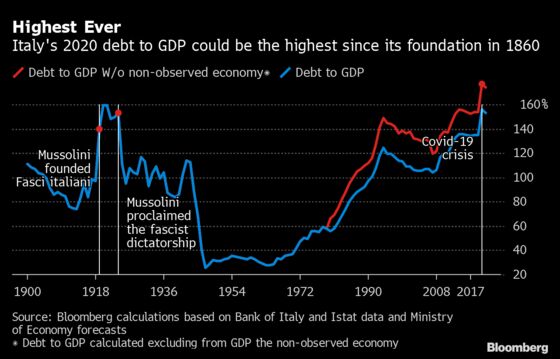

While the economic and political gulf between north and south is still widening, the pandemic has carried Italy through an economic looking glass: even with the budget deficit forecast to be wider than in 1992, the year of the last devaluation, no one is carping about spending to revive an economy that’s barely budged for decades. The European Commission sees gross domestic product shrinking 9.5% this year, after a 4.7% decline in the first quarter, the worst drop since the series started in 1995. That could swell its already massive debt to well over 150% of GDP.

“Rome must spend to avert deep economic crisis,” says David Powell, Bloomberg Economics’ senior euro-area economist.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.