Exxon Finally Speaks Up as Chevron Catches Up

Exxon Finally Speaks Up as Chevron Catches Up

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Exxon Mobil Corp. wants you to know it is serious. On Friday morning, Darren Woods became the first CEO of the famously aloof oil major to grace an earnings call in 15 years.

Fortunately for him, he had some decent results to talk about. After several quarters of decline, year over year, Exxon’s production finally ticked up in the last few months of 2018. Earnings of $1.41 a share handily beat the consensus forecast of $1.08. They still do even after stripping out about 20 cents’ worth of one-off benefits. Cash flow from operations for the year, a cool $36 billion, more than covered rising capital expenditure of almost $21 billion as well as dividends of almost $14 billion.

Yet Woods didn’t show up just because the numbers were good. He was there to assuage concerns about Exxon’s slipping crown.

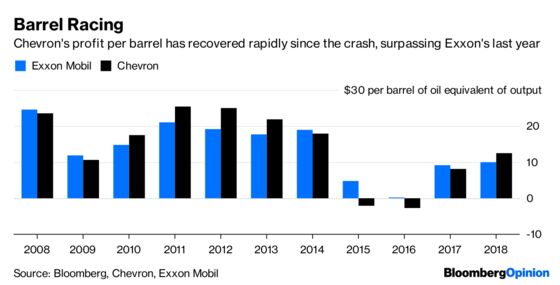

As usual, compatriot and rival Chevron Corp. announced results the same morning. One of the more striking sets of numbers was the two companies’ upstream earnings: Chevron’s full-year figure of $13.3 billion wasn’t too far off Exxon’s $14.1 billion, despite the latter’s production being 18 percent higher. While Chevron’s earnings per barrel of oil equivalent collapsed into negative territory during the crash, it has since caught up and surpassed its bigger rival:

On a range of metrics, Chevron has been catching up. A decade ago, its production and earnings were 69 percent and 54 percent as high as Exxon’s, respectively. In 2018, those figures were 76 percent and 71 percent – and Exxon’s benefit from a large chemicals business.

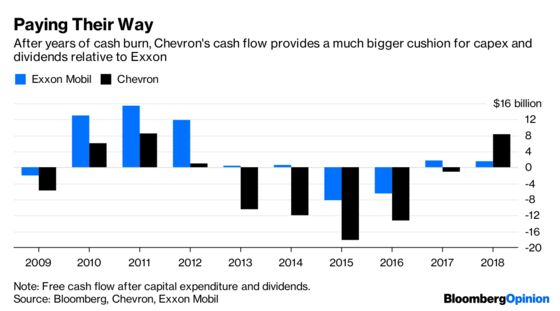

Where this really comes through is in what investors care most about in the oil sector these days: cash. Chevron’s free cash flow surpassed Exxon’s last year for the first time in at least a decade . More importantly, Chevron’s free cash flow after dividends of $8.3 billion in 2018 was five times the size of Exxon’s.

There’s a cyclical element at play here, of course. Chevron was in the doghouse only a few years ago as it digested some giant investments in new projects, just as Exxon is investing in new growth projects now. Nonetheless, this is why Exxon’s dividend yield now trades consistently above Chevron’s; and yet the latter stock yields more overall due to buybacks, which remain conspicuous by their absence at Exxon. As if to hammer home the point, Chevron announced a $25 billion repurchase program on its own Friday-morning call.

Both companies have moved aggressively in U.S. shale, previously the preserve of their smaller rivals. Both touted a near doubling in their production from the Permian basin in the fourth quarter compared with a year earlier. Here again, though, the numbers show Exxon in an uncharacteristic runner-up position. Earnings from its U.S. upstream business in 2018 of $2 billion were more than a third below Chevron’s, despite Exxon’s output being 24 percent higher (Chevron’s is much oilier).

All this leaves Exxon in the unfamiliar position of having to prove itself. The day before the gesture of Woods’s appearance on the earnings call, the company announced it was streamlining its upstream exploration and production business – the giant heart of this giant enterprise – from seven companies down to three. In offshore Guyana, Exxon has perhaps the most exciting discovery anywhere in the global industry. Its integrated business model, meanwhile, offers one way – albeit not yet proven – for an oil major to gain some advantage in shale.

Even so, Chevron isn’t standing still. Its acquisition of the Pasadena refinery in Texas, announced earlier this week, speaks to its own strategy for making integration pay in shale. It claims 70 percent of its capex budget delivers cash within two years, a very un-major-like payback schedule. Hence, Chevron is forecast to deliver $46.5 billion of free cash flow over the next three years – slightly higher than Exxon’s and equivalent to more than 22 percent of market cap, while Exxon yields less than 16 percent.

On any number of measures, Exxon still trades at a premium, albeit less than it once was. For example, its price/book ratio of 1.52 times is 12 percent higher than Chevron’s. Just five years ago, the gap was 62 percent. Woods is working hard to restore those glory days. The difficulty is that, based on current performance, justifying even today’s premium requires some serious marketing.

I'm using the definition of cashflow from operations less capital expenditure; not including proceeds from disposals, as the oil majors do.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Mark Gongloff at mgongloff1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Liam Denning is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy, mining and commodities. He previously was editor of the Wall Street Journal's Heard on the Street column and wrote for the Financial Times' Lex column. He was also an investment banker.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.