Everything Wrong With a Bullish Case on Stocks Tied to Bonds

Trying to discern a positive message for equities in the harrowing plunge in Treasury yields? You may be deluding yourself.

(Bloomberg) -- Trying to discern a positive message for equities in one of the more harrowing plunges anyone can remember in Treasury yields? You may be deluding yourself.

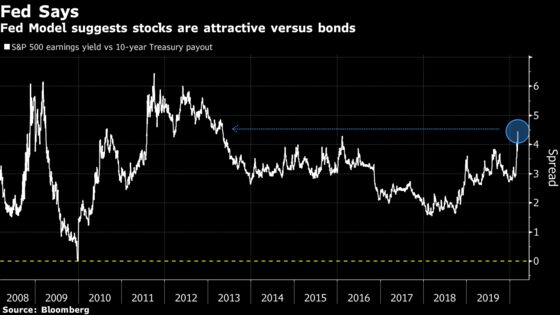

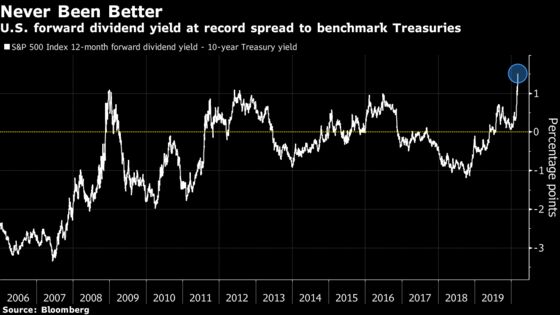

Yes, by some measures, with each leg down in yields, equity valuations get more tempting. The S&P 500’s 12-month forward dividend yield is the highest relative to benchmark 10-year Treasury rate on record, data compiled by Bloomberg show. And the so-called Fed model, which compares the S&P 500’s earnings yield to bonds, suggests equities are the biggest bargain since 2013.

But simply looking at those superlatives misses an important consideration: Rates are low for a reason. The rapid spread of the coronavirus and its implications for global growth pushed 10- and 30-year Treasury yields to record lows last week, while roiling risky assets. While that’s made for more attractive equity valuations, the dire scenario priced in by bond markets far outweighs the positive, according to Richard Bernstein Advisors.

“The biggest reason that rates are so low is because they’re discounting a collapse in growth,” said portfolio strategist Dan Suzuki. “If you start to discount a global recession, which is pretty close to what interest rates are trying to price in, how can that be positive for stocks?”

Yields on benchmark U.S. debt slid as low as 0.66% on Friday, while rates on 30-year bonds fell to an all-time low of 1.20%. That was partly thanks to an emergency 50-basis point rate cut from the Federal Reserve, with Chairman Jerome Powell citing the outbreak’s risks to the U.S. outlook.

Those records were set before Saudi Arabia slashed pricing for its crude by the most in more than 30 years on Sunday after its OPEC+ alliance with Russia collapsed. The shock to sentiment combined with the potential deflationary effects of lower oil prices could fuel the next leg lower in Treasury yields.

While the S&P 500 Index managed to end last week in positive territory, it’s seen historical turbulence. The Cboe Volatility Index, or the VIX, has hovered above 30 for seven straight sessions. That’s the longest such streak since 2011, and well above the gauge’s five-year average of 15.

As of Friday, there were 388 companies in the S&P 500 with a higher dividend payout than the 10-year Treasury rate, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. That compares with 241 companies at the start of the year.

The widening yield advantages have done little to sway Peter Cecchini at Cantor Fitzgerald LP. Stacking up dividend yields to bond rates is an “apples to oranges comparison” that says little about equity valuations, he said.

“It’s a risk versus risk-free argument,” said Cecchini, Cantor’s chief market strategist. “When companies earnings go down, they may not pay out the same amount.”

Moreover, equities remain “outrageously overvalued” when considered alongside still-tepid U.S. inflation, in Cecchini’s view. Demand-driven price pressures tend to buoy corporate profits, feeding into higher wages and boosting long-term interest rates.

“Inflation is low, growth is low, earnings are likely to not grow as fast in that environment,” Cecchini said. “Therefore, ‘rates are low’ does not justify a lower equity risk premium.”

Warranted or not, the allure of dividend yields may prove overpowering as rates on long bonds continue to crater. While buying equities as a substitute for fixed-income isn’t foolproof -- a 5% dividend yield won’t be much comfort if the stock falls 6% -- investors will ultimately abandon the bond market, according to Randy Frederick of Charles Schwab.

Case in point: utilities. Sought-after for the sector’s defensive qualities and relatively lofty dividend payouts, utilities are still clinging to a 2% year-to-date gain, while the broader S&P 500 has slumped nearly 8%.

Still, Frederick’s staying away. A hunt for yield has pushed the sector’s forward price-to-earnings ratio to 20.7 on Friday, down only slightly from an all-time high of roughly 21.7 reached in mid-February.

“There’s been so much desire to get dividend-paying stocks, which tend to be heavily concentrated in the utility sector, that valuations have gotten way out of hand,” the vice president of trading and derivatives at Charles Schwab said. “The challenge is as rates go down, it doesn’t mean people won’t continue to buy it.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Katherine Greifeld in New York at kgreifeld@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Jeremy Herron at jherron8@bloomberg.net, Chris Nagi

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.