Europe’s Inflation Shock Fizzles in German Post-Crisis Pay Talks

Europe’s Inflation Shock Fizzles in German Post-Crisis Pay Talks

(Bloomberg) -- Sign up for the New Economy Daily newsletter, follow us @economics and subscribe to our podcast.

The prospect that Europe’s surging inflation could stoke pay is being put to the test in the region’s largest economy as 3.5 million Germans in the public sector struggle to secure significant raises in wage talks.

With annual consumer prices rising there by 4% and heading even higher, a new round of negotiations on Nov. 1 will help show if the post-crisis landscape has bolstered bargaining power at the heart of the euro zone. The evidence so far doesn’t favor the workers.

While a hard push back from employers set the scene for a round of strikes, it would also provide a clue to European Central Bank policy makers wondering if the pandemic has fostered a sea change in inflation after years of lackluster price increases. That judgment is crucial as officials prepare to reinvent stimulus for after the crisis.

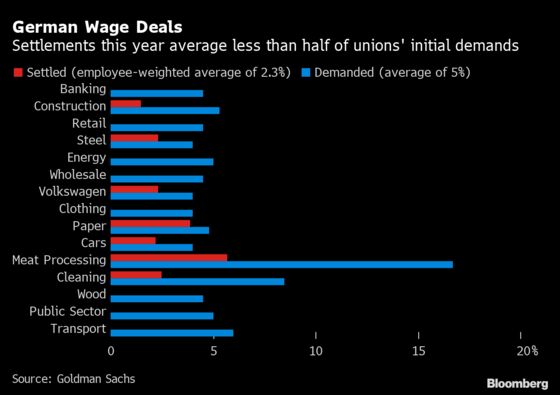

Leading the talks is Ver.di, Germany’s second-largest union, which is seeking a 5% raise for employees of federal states in a deal likely to be replicated across the public sector. Other agreements -- including one for public-sector workers in the state of Hesse negotiated separately -- point to final increases likely to be less than half of that, reflective of an economy still nursing crisis wounds.

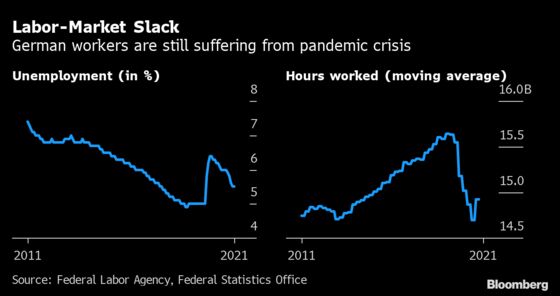

“It would be quite unusual to get a wage agreement of 5% in an environment where the labor market still has spare capacity,” said Jari Stehn, chief European economist at Goldman Sachs Group Inc. in London. “That usually only happens when you have a tight labor market, which is not really the case at the moment.”

As a backdrop to the negotiations, higher energy costs and global trade bottlenecks have caused a major price spike in euro-zone inflation, which likely hit 3.7% in October. In Germany, the Bundesbank predicts the rate will approach 5% at the end of the year.

The question of whether such inflation will feed into wages is key for the ECB. Officials reckon current price increases will prove transitory, but hawkish policy makers cite pay pressures as a reason to consider winding down stimulus.

“Upside risks, in the short to medium term, are mainly linked to more persistent supply side bottlenecks and stronger domestic wage-price dynamics.”

--Dutch central bank Governor Klaas Knot on Oct. 14.

That risk has yet to materialize in Germany. Employers have rejected Ver.di demands including at least 150 euros ($173.44) more a month -- double the amount for the health sector. Chairman Frank Werneke is committed to a hard fight.

“Public sector colleagues have kept this country going,” he said in a video message this month. “We’ve received applause and encouragement, but we’re saying applause alone doesn’t cut it, and now prices are rising too.”

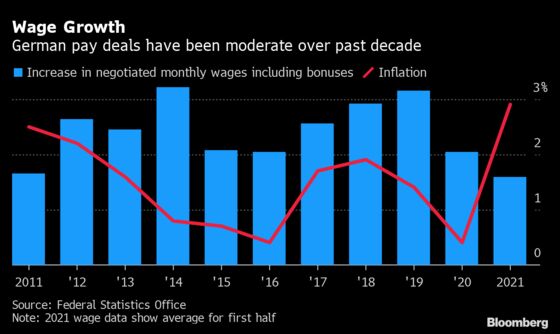

Despite such tough talk, recent deals show unions settled for average increases of just over 2%. That’s below a formula saying raises aren’t inflationary until they exceed productivity growth plus expected price gains, which would be 3%.

Jobs-market slack might partly account for such outcomes, as Stehn of Goldman Sachs suggests -- unemployment remains higher than before, and supply shortages have sent more factory workers into furlough -- but the results also reflect the subtle nature of bargaining in Germany.

“Labor unions may bring up high inflation rates during the negotiations, but normally they have their eyes on the medium to long term,” said Sebastian Dullien, research director at the Macroeconomic Policy Institute in Duesseldorf, a think tank close to the unions. “They understand agreements that would lead to faster inflation are of no use.”

Long Memories

Informing that view is a 1970s episode where a wage spiral sent the economy into a recession and ended full employment in Germany.

Many companies are also still struggling with aftershocks of the pandemic, rebuilding capital buffers or repaying loans.

Still, there’s a chance pay pressures could build further. Personnel and management consultancy Kienbaum expects German wages to rise an average of 3% next year. Some sectors facing labor shortages may see bigger gains.

Germany’s minimum wage is set to be boosted by 25%, a win for Finance Minister Olaf Scholz in negotiations to form a government under his leadership after he led his Social Democrats to victory in September elections.

Whatever public-sector workers accept may influence other negotiations. IG BCE, which represents some 600,000 mining, chemical and energy workers, will present wage demands next month before bargaining starts in March.

Companies in those industries harbor even more job-preservation worries at a time when the economy is being transitioned toward a climate-friendly, digital future that might threaten traditional manufacturing.

Associated investment costs will also limit room to grant higher pay, according to Hubertus Bardt, head of research at the German Economic Institute in Cologne, a think tank aligned with employers’ groups.

“Switching a steel plant to green production costs billions without increasing capacity,” he said. “We mustn’t force firms into wondering if they should invest here or elsewhere.”

| Read more: |

|---|

|

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.