A Church’s Ethical Investing Mission Gets a Reality Check

A Church’s Ethical Investing Crusade Gets a Reality Check

(Bloomberg Markets) -- At the London Stock Exchange, Justin Welby’s bright-white clerical collar stood out in a sea of dark bespoke suits and silk ties. Welby—the archbishop of Canterbury, 105th leader of the Church of England—had come to address representatives of global investment firms that oversee $40 trillion in assets. He was leading an initiative that used religious and financial clout, God and mammon, to push corporations to help save the planet from a climate catastrophe.

Welby was well suited for this October gathering. Before being called to the ministry, the 65-year-old cleric had worked as an oil industry executive for Elf Aquitaine in Paris and Enterprise Oil Plc in London. Now he was promoting the Transition Pathway Initiative, which would help money managers evaluate corporations’ readiness for a low-carbon economy. “We want companies to change their actions, not merely to hear our words,” he told the crowd. BlackRock Inc., the world’s largest money manager, signed on.

The Anglican Church, an early proponent of socially responsible investing, has quite the pulpit: 26 million members and its spiritual leader, Queen Elizabeth II. But, for all the acclaim it’s drawn, the church’s quest is also a parable with a less-than-uplifting message for those who care about what’s come to be known as environmental, social, and governance, or ESG, investing. In one of its signature initiatives, the Church of England has struggled to change corporate behavior.

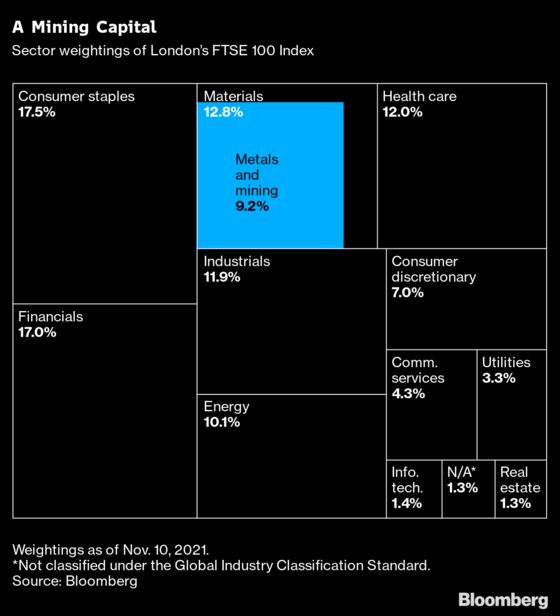

For almost a decade, the church has tried to use its influence to improve the safety, environmental, and human-rights records of the world’s mining industry. It is well positioned to do so. Some of the world’s biggest mining companies have roots in a British colonial empire that once dominated the world’s natural resources. Today, four mining giants— Rio Tinto, Glencore, BHP Group, and Anglo American—make up almost 9% of the market value of the FTSE 100 Index of the most valuable companies trading on the London Stock Exchange, among the most significant weightings of any industry.

The church’s decision to work with mining conglomerates, rather than call them out, has divided the faithful, especially leaders in the U.K. from those in the developing world. Skeptics, including Richard Solly, coordinator of an alliance of human-rights, development, and environmental groups known as the London Mining Network, say the church has grown too close to the companies. They point to industry promises on the environment and worker safety that have been made and broken. The cooperation between some church leaders and mining officials, Solly says, “is a disastrous mistake—it’s allowed the mining companies to capture the reputation of the church.”

After the October ceremony, Welby was asked about the complaint that the church is being used for “greenwashing,” or helping companies to market their environmental bona fides while they continue to damage the environment. “It’s a fair question,” the archbishop replied. But then he paused and, like a good pastor, grew thoughtful. Welby returned to a lesson from Scripture: “The Pharisees said Jesus is a bad guy because he’s mixing with sinners. Well, yeah, that’s how you change things. It’s not going in as holier than thou; it’s going in and saying, ‘There is a common problem about how human beings are being treated, how the environment is being treated, how the planet is being treated. We can change that together.’ ”

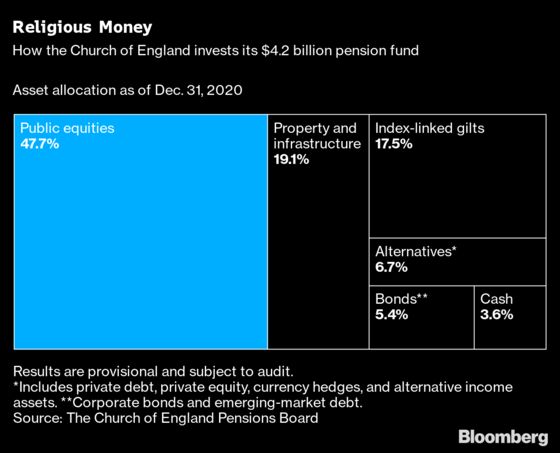

The Church of England established its ethical investment policy in 1948, when its endowment started buying stocks. Today, its Pensions Board, which manages $4.2 billion for 41,000 people, magnifies the church’s financial power by allying with like-minded religious and secular money managers. “We’re there at the front of various tens of trillions” in socially conscious investments, says Adam Matthews, the board’s chief responsible investment officer, who previously worked with a group co-founded by uber-environmentalist and former U.S. Vice President Al Gore.

Matthews, 45, gets up each day at his home in Edinburgh and climbs Arthur’s Seat, an ancient volcano just outside the city. Last year trade publication Environmental Finance named him its “personality of the year,” citing the church’s ethical investment initiatives. “Matthews is seen to have moral authority,” says Paul Watchman, a lawyer who’s worked on sustainable investment for the United Nations. “BlackRock’s Larry Fink may send out a letter to CEOs, but Matthews’s communications are more like the Letters to the Corinthians.”

Anglicans know full well the litany of ills associated with mining: child labor in Congo, the site of much of the world’s cobalt mining; threats to Indigenous community rights and livelihoods from Alaska to Papua New Guinea because of the extraction of copper, silver, and nickel; modern slavery linked to mines in places including Ecuador and Eritrea.

Then there’s the environmental toll. Mining accidents in Peru have resulted in lead and mercury poisoning. The industry is directly responsible for as much as 7% of all greenhouse gas emissions, according to consultant McKinsey & Co. Add in the emissions produced by burning extracted coal for power generation and to make steel, and the total rises to 28%.

Yet the church has long argued that mining, like sex, can serve either God or the devil. “We cannot simply refuse to be involved with the extractive industries purely because of past mistakes or former ways of behaving,” the church said in a 2017 encyclical. It called mining “a dangerous business, with a larger share of pain and crucifixion” but also “a way of bringing new life to areas of the world.” The industry’s excavation of copper and lithium is essential for electrification and the fight against climate change. In an age of growing environmental awareness, mining companies certainly need open-minded allies. In a study this year, law firm White & Case found that 45% of decision-makers in the mining and metals sector expect ESG issues to represent the largest risk to their industry.

Mining executives first suggested an industry-church partnership. In the fall of 2013, a delegation traveled to the Vatican for “days of reflection” and, the next year, to Lambeth Palace, the London residence of the archbishop of Canterbury. Led by Mark Cutifani, chief executive officer of Anglo American, the colloquy included Rio Tinto’s then-CEO Sam Walsh, Newmont’s then-CEO Gary Goldberg, and Australian billionaire Andrew Forrest, chairman of Fortescue Metals Group. “It’s about good business,” Cutifani says of the initiative. “No one ever created a 100-year company upsetting people and doing things badly.” Delegations of U.K.-based clergy and other religious leaders took trips, funded by the industry, to mining sites around the world.

At times, there was a backlash from their colleagues who were closer to the ground. In Lima, Anglican, Presbyterian, Methodist, and evangelical leaders took turns to “condemn mining in all its forms,” says Daniel Finn, a U.S. theology and economics professor who visited Peru in 2015. “Mining has done such terrible damage in Peru—polluting the water, polluting the air, abusing the people—and there was just no room for any kind of openness for whether some mining companies might be doing it differently.”

In 2017, Glencore Plc, the Swiss commodities trading and mining giant, and other companies invited Anglican and fellow church leaders to Cerrejón, an open-pit coal mine in Colombia. Environmental justice groups complained that the trip was skewed to favor the industry, and the delegation spent little time listening to locals. Dozens signed a statement: The religious visits, “instead of acting as an instrument of transformation, may act as a sort of formal legitimation.”

Brazil’s Vale SA, one of the world’s largest producers of iron ore and nickel, confronted the Church of England with especially wrenching choices. Anglicans led a global campaign to improve the safety of tailings dams, or waste mounds designed to keep toxic sludge in check. In 2015 a tailings dam at a Brazil iron ore mine co-owned by Vale collapsed. The accident killed 19 people and caused enormous damage to the environment, including to downstream drinking water.

Vale pledged reform, listed its ESG commitments in annual sustainability reports, and won top placement in a ranking of companies committed to human rights. The church continued to own Vale shares.

But in January 2019 a dam at a Vale iron ore mine in the town of Brumadinho, Brazil, collapsed and caused a far deadlier catastrophe. As the ground gave way, it crumbled into a churning tidal wave of poisonous waste that flattened buildings, demolished forests, and killed 270 people. Matthews was horrified, and the Church of England’s pension fund sold its Vale stock.

Another investor in Vale, the Colleges of Applied Arts & Technology Pension Plan in Canada, took a more confrontational approach. The year of the disaster, the fund filed a federal lawsuit in Brooklyn, N.Y. The pension plan alleged that Vale’s statements related to ESG efforts—the very kind that involved the Anglican Church—were part of a broader effort to deceive shareholders about the true nature of the company’s operations. The complaint, which seeks class-action status, cited internal red flags about the dam’s dangerous condition that were revealed in a government investigation. In court filings, Vale denies the allegations, saying the lawsuit oversimplifies or mischaracterizes aspects of iron ore mining and tailings dams. Separately, in February, Vale agreed to pay $7 billion to the state of Minas Gerais, where the mine is located. The money will repair damage from the collapse. In a statement, Vale said it took extraordinary measures to help affected communities, vigilantly mitigates risk, and is “building solid ESG practices.”

The Church of England didn’t give up on working with the mining industry. Matthews teamed up with John Howchin, secretary general of the council on ethics of the Swedish National Pension Funds, and gathered investors for another safety push, called the Investor Mining and Tailings Safety Initiative. To avoid yet another disaster, it would pressure companies to disclose for the first time the locations of their tailings dams and answer questions about their adherence to what it called a “global industry standard.”

As of May the initiative had contacted more than 700 publicly traded mining companies, and most have made full or partial disclosures about their tailings dams. Last year the effort won “Stewardship Project of the Year” from a UN-supported responsible investment initiative.

But two of the seven experts who developed the monitoring standard later said the results heavily favored the industry. They published a critical book called Credibility Crisis: Brumadinho and the Politics of Mining Industry Reform. The authors, Andrew Hopkins and Deanna Kemp, Australian academics specializing in industrial safety and social justice, didn’t dismiss entirely the push for a monitoring standard or the role played by investors. But they said an industry group, the International Council on Mining & Metals, repeatedly—and successfully—pushed for lower standards, saying they wouldn’t otherwise sign on. The mining industry “largely controlled the process” after investors established the global standard. (The mining council says expert opinions inevitably differ.)

Rodrigo Péret, a Franciscan friar from the Brumadinho region, was less measured. “The miners need this cozy relationship with the church, because resistance in the field means delays to licenses,” he says. “They want to generate a favorable environment for themselves and change the narrative.”

Cutifani, Anglo American Plc’s CEO, says such criticism is unfair. “The fact that we’re still here 10 years after we started this, and we’re still in the dialogue, and we’re still doing stuff in South Africa, we’re doing stuff in Peru, and we’re doing stuff in Chile, that, at least, shows that there’s a will to do better,” he says.

Matthews remains undeterred. Mining to produce the raw materials needed for a low-carbon world is essential, he says, to “human flourishing,” as well as business success. “To pretend that mining is going to go away just doesn’t sit as realistic,” he says. “The future is a future of very unusual partnerships and alliances.”

The Church of England continues to push mining companies, including Vale, to disclose information about their dams. The church hasn’t gone so far as to buy Vale shares again. Matthews is still talking with the company.

Marsh reports on green finance and ESG investing in London. Bronner is a senior editor in New York.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.