Diary of a Crisis: Inside Wall Street’s Most Volatile Ever Week

“This week feels like it’s lasted about 30 days.”

(Bloomberg) -- “This week feels like it’s lasted about 30 days.”

Tim Courtney, chief investment officer at Exencial Wealth Advisors in Oklahoma City, spoke for everyone who rode the markets in its most volatile stretch.

This was a week of escalation. Of the coronavirus and the countermeasures. Of the economic hit and the policy response. Of investor fear and market stress. In the space of six days, warning lights flashed in the deepest recesses of global markets, a decade’s worth of monetary action, and a scramble for liquid assets surpassing any that went before.

Drawing from coverage across the Bloomberg News markets team, this is the story of the chaos that unfolded on Wall Street and beyond.

Shock, No Awe

Sunday 15 March: By about 5 p.m. in New York on Sunday it’s already clear: It will be another historic week in markets.

Just as trading was resuming, the Federal Reserve stuns everyone with another emergency rate cut and a promise to boost its bond holdings by hundreds of billions of dollars.

The move is a shock and it’s meant to be. The Fed is trying to protect the world’s largest economy from the impact of a pandemic that has already started to shut down vast swaths of industry and commerce. It also wants to ease stresses that have been rising in various corners and which, if ignored, can spiral out of control with dire consequences for the real economy.

This huge move of policy support should be well timed for investors. U.S. stocks just posted one of their best days in more than a decade, a dramatic bounce spurred by President Donald Trump’s press conference on March 13 where he detailed plans to fight the virus.

The only trouble is, we have seen these rallies before, and they are often a signal of misfiring markets as much as anything else. The last such surge was in October 2008.

So investors are already nervous. The massive emergency action feeds into the unease as market players wonder what central bankers know that they don’t. In the New York evening as trading begins, S&P 500 futures tank. They hit their lower trading curbs once again and don’t come back.

The nerves feed into the currency market and that reliable old haven, the Japanese yen, strengthens. The New Zealand dollar slides after its central bank also slashes rates. In the bond market, Treasury futures predictably surge.

2,997 Points

Monday 16 March: S&P 500 futures have dropped by as much as they are allowed under the rules that prevent outsize moves at times of low liquidity. So like last week, investors turn to the exchange-traded fund that tracks the benchmark, which trades in the pre-market without limits.

It doesn’t look good.

Monetary and government officials are pledging action left and right. The central bank moves are coordinated. The International Monetary Fund says it’s ready to mobilize its $1 trillion lending capacity to help nations counter the coronavirus. And none of it seems to be enough.

Stocks are down heavily in Europe and Asia. When the cash market opens on Wall Street, the trading halt for the S&P 500 is nearly instantaneous as the gauge plunges 8.1% -- falling so fast it goes beyond the 7% mark where the halt should kick in. Fewer than 100 shares actually manage to trade in that instant. When the 15-minute circuit breaker ends, the losses mount. The S&P 500 will end 12% lower.

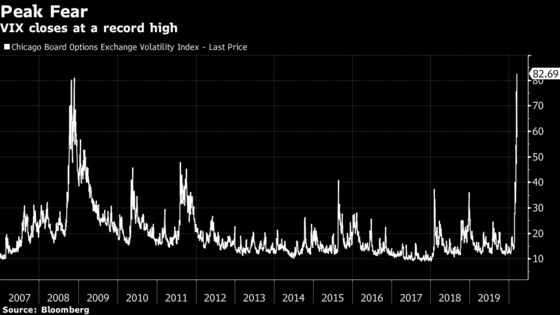

Meanwhile in the options market, investors trade contracts based on what they expect the S&P 500 to do in the future, the ones that form the VIX Index. It’s essentially a barometer of expected volatility. It climbs to the highest intraday level since November 2008, and it will close at a record.

The problem is confidence. Investors are nervous, and for every bit of policy support there’s a bad headline to cancel it. A gauge of manufacturing in New York State plunges the most ever. The White House tone shifts -- the country may be headed for a recession, Trump says. Europe is now reporting more coronavirus cases per day than China at the peak of its outbreak. The region is considering shutting down non-essential travel.

The sheer scale of gold’s move escapes mainstream attention, but it goes from a peak of gaining 3% to losing as much as 5.1%. European bonds are in turmoil, with a measure of market stress hitting levels not seen since the 2011-2012 euro crisis.

“The worst outcome at the moment is there’s nowhere to hide,” says Klaudius Sobczyk, a fund manager at PEH Wertpapier AG in Frankfurt. “Your gold is falling, your equities are falling, your bonds are falling. There is no safe haven.”

At this moment, Sobczyk is one of an increasingly rare breed: He’s a money manager still working in his office. He has prepped to operate at home though, and while the bars and restaurants in Frankfurt remain open, it’s a matter of time -- they’re already shutting in Bavaria and Berlin. Remote working hardships are destined to play a role in asset action later in the week.

The Stoxx Europe 600 Index finishes Monday at the lowest in seven years. The gloomy mood is compounded when filings show Bridgewater Associates, the world’s biggest hedge fund, has built up a $14 billion bet that shares in the region’s companies will continue to sink.

In all the noise, some will have missed the relentless decline of oil. Both WTI and Brent dip below $30 per barrel, Brent for the first time since 2016.

Trouble continues in credit, too. The cost to insure dollar- and euro-denominated debt against default rises to new highs as investors doubt what monetary policy can do to stem the risk of recession. A corner of the financial system that provides corporate America with short-term IOUs to buy inventory or make payrolls, the commercial paper market, is seizing up.

One piece of good news, at least: Only $19 billion of the Fed’s $500 billion repo offering is taken up. This suggests to some that the Fed has averted a funding crisis for now.

But the truth is, as scary as a credit crunch would be, that’s not what markets are panicking about right now. They’re panicking about an economic crunch in the face of unfolding human tragedy -- and more cash sloshing through the system won’t help corporations as customer demand craters.

The Dow Jones Industrial Average loses 2,997 points to take the plunge from its record high just over a month ago to 30%. Two of the last three days have been among its worst in history.

“It appears the more central bankers and the governments try to do, the less the markets really like it.” says Sobczyk.

‘No Joy’

Tuesday 17 March: Trading is choppy in Asia, and sets the scene for what will follow in Europe and the U.S. We’re about to have a big bounce, but confidence will be absent from start to finish.

The S&P 500 jumps as much as 7% after trading in the red earlier, continuing a streak of volatility the like of which has not been seen since the Great Depression. In fact, volatility is one of the few winners from this virus outbreak so far.

An asset class of its own, volatility has been in a period of structural decline across stocks, bonds and currencies for years in the era of ultra-low rates and QE. Now the moves have become so extreme that it is stirring speculation a collection of investors who adjust their strategies based on price swings may actually be exacerbating things.

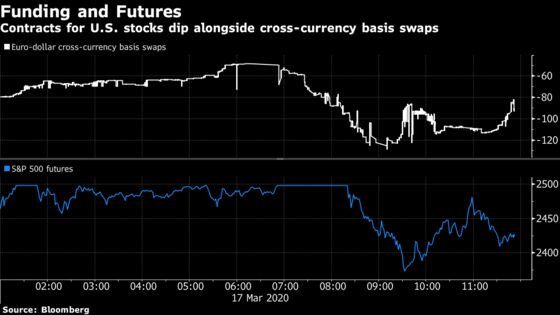

In the money markets the alarm bells continue to ring. During the European morning, cross currency basis swaps for euro-dollar, which signal how expensive it is to get the greenback, suddenly move to the widest since 2011. They come back under control, but in a graphic example of the interconnected nature of financial markets, futures on the S&P 500 move in the minutes that follow:

Later in the day the three-month dollar Libor rate, a proxy for tension in financial markets, jumps the most since the crisis. The clamor for dollars sends America’s currency surging in the spot market. When a survey shows German investor confidence collapsing the euro plunges, lending the greenback even more momentum.

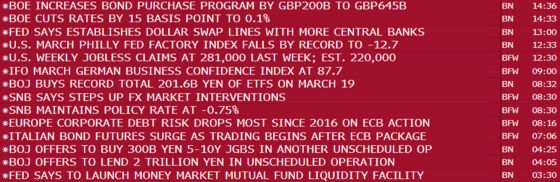

Faced with this kind of drama, the European Central Bank, Swiss National Bank and Bank of England announce they will provide liquidity under a so-called swap arrangement coordinated with the Fed. The U.S. central bank also reveals it will restart a financial crisis-era program to help American companies borrow using commercial paper.

The signs of stress ease, but they do not go away.

Dev Kantesaria is founder of hedge fund Valley Forge Capital Management based in Wayne, Pennsylvania. He went to Harvard Medical School and has friends in the emergency room who tell him stories about dwindling supplies and growing patient intake as the coronavirus spreads, and other doctors who talk to him about the limited availability of tests.

“People and investors still don’t understand the gravity of the situation,” Kantesaria says. “I still do not believe the market reaction today reflects the full outcome of what’s going to happen over the next three to six months.”

There are plenty of clues. Data shows U.S. retail sales fell in February, indicating the main driver of the economy, consumer spending, had begun to slow even before outbreak containment measures began.

It may seem a long way from Wall Street, but in Norway the number of people seeking unemployment benefits surges 128% in a week. The European Union effectively shuts its borders in a bid to slow the spread of the illness. The region’s biggest industrial manufacturers, from Volkswagen AG to Airbus SE to Daimler AG, idle plants.

“There really is no joy,” says Kantesaria. “It’s a grim time, whether someone’s making money or not.”

In that light, the blaze of big announcements later on Wednesday come as less of a surprise. The U.K., which just days ago unveiled the biggest peacetime stimulus in living memory, tears up the peace and goes to a war footing, pledging hundreds of billions more to help protect the economy.

The Trump administration talks about sending checks to Americans in a matter of weeks to stave off the financial effects of an unprecedented upheaval in social interactions that looks set to plunge the world into recession. It asks Congress for hundreds of billions in aid.

It’s time for Treasuries to plunge as the scope of all this planned spending sinks in. Government borrowing will have to surge. The yield on 10-year U.S. notes rises by the most in a single day since 1982.

Correlation

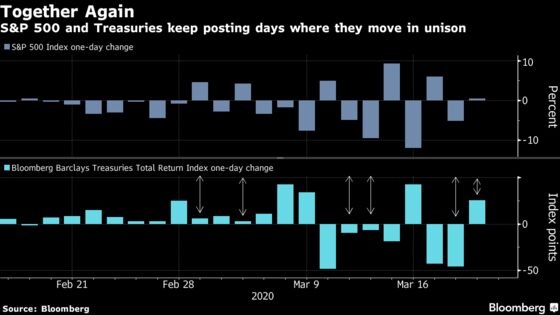

Wednesday 18 March: Stocks are moving with bonds, and that doesn’t usually happen.

Treasuries are extending their declines from a day earlier as investors adjust for the expected wave of new government borrowing. Municipal bonds extend the deepest rout since 1987. Sovereign debt in Europe follows suit as Germany hints at the possibility of joint EU issuance for the first time.

Equities are also sliding today as the economic impact of the virus seems to outpace the policy response. The S&P 500 endures its second trading halt in three days, another reversal from the prior session that helps push the VIX Index to its highest intraday level ever. All the U.S. stock gains since Trump was elected have pretty much vanished.

Traditionally government bonds tend to rise when stocks fall and vice versa, meaning a classic strategy uses the debt to hedge an equity portfolio. That isn’t working today. Gold is down, too. Traders are running out of havens again, and in desperation they are dashing for cash.

Read more: Market Stress Spikes at a Pace Almost Matching 2008 Crisis

This has all the hallmarks of a crisis. But it may not feel like it yet for many in the market, since the coronavirus means they’re working at home.

Peter Sleep, a fund manager at Seven Investment Management LLP in London, spent Monday glued to a Bloomberg screen watching events unfold with colleagues. By Tuesday he was at home alone.

“There are announcements of government support that seem significant, but the confirmatory flow from around me is not there,” he said. “Given the lack of noise and pressure around me, I don’t really feel any stress.”

By the end of Wednesday trading, its doubtful Sleep would need anyone around to confirm how serious things were. European cases of coronavirus now top China. Bloomberg’s dollar index hits an all-time high as investors go to the safest and most liquid thing they know. The pound plunges amid talk London could be locked down to prevent the spread of the virus.

Physical constraints shouldn’t stop the world’s largest foreign-exchange hub functioning, but the psychological impact is real enough to hit liquidity and help fuel these moves. The strains in the funding markets re-emerge late in the day.

Market breakdowns feel swift and brutal, but often they are about attrition. The central bank actions had a positive impact in many areas of the market, but in the corporate bond sphere the stress has barely let up. The $3.9 trillion state and local government bond market in the U.S. is seeing yields surge as investors pull out their cash. That has saddled investors with their biggest losses since 1987 and effectively locked states and cities at least temporarily out of the bond market.

Credit risk gauges in Europe and Asia push out further. The tumult even starts to reach Japan’s $650 billion local credit market, until now an oasis.

Oil, already battered, plummets another 24%. Remarkably, it’s not even crude’s worst day this month. The crash feeds into the Norwegian krone, which at one point weakens more than 10%. Industrial metals like copper tank as the economic storm clouds gather.

Late in the day, the ECB convenes an emergency meeting.

Action

Thursday 18 March: Not only is there not much awe at the moment, at this point there’s not much shock. Thursday is a rolling series of central bank and government interventions to keep financial markets ticking and economies propped up, and in some sections of the market it’s the calmest day in more than a week. Investors now know for sure that central banks will do whatever it takes, and that helps restore some order.

In Europe, they know because the ECB literally told them so. The emergency gathering has led to an extra emergency bond-buying program worth 750 billion euros ($820 billion), and a pledge to consider revising its quantitative-easing limits. President Christine Lagarde tweets:

The bond market is one place that is not quiet. Government notes across Europe surge on the prospect of more central bank purchases. The measures announced include Greek debt for the first time, and yields on that nation’s bonds at one point drop more than 200 basis points. The region’s corporate debt risk falls by the most since 2016.

The ECB news came overnight, but it’s just the start. The Bank of Japan buys bonds throughout the trading day. The Fed says it’s going to launch a money market mutual fund liquidity facility. The Reserve Bank of Australia cuts rates. Even the Philippines gets in on the action, announcing a rate cut by text message hours ahead of schedule. The country’s stock index has crashed 13% after reopening from a shutdown.

On and on. The Bank of England restarts QE and makes another emergency cut to rates. Swedish policy makers step up crisis support. Germany mulls declaring a state of emergency to pave the way for unlimited borrowing.

It’s a barrage of action with few precedents, but in markets the reaction feels muted compared to recent wild moves. Then again, perhaps that was the intended outcome. And the mood music overall seems positive.

There are no trading halts or limits hit in U.S. stocks or their futures. The VIX index retreats a little. European shares notch the best day since 2016. After its horror show on Wednesday, Trump jawbones oil to the best day it has ever had. Even credit gets a ray of light, as borrowers in both Europe and America bring the primary market back to life.

Dive a little deeper, however, and there are aftershocks from the recent extreme swings and declines. The dollar rises an eighth day, taking Bloomberg’s index to the highest in its 15-year history. The amount of debt trading at distressed levels in the U.S. corporate market has doubled in two weeks. There’s no let up for municipal bonds.

Burned by the market meltdown, hedge funds are scaling back. And in the dramatic bond moves some on Wall Street have seen the telltale signs of what are known as margin calls, where brokers demand extra collateral from investors to cover losses in their leveraged accounts. This can trigger further selling, and has been a feature of several major financial blowups.

“It was so fast and so furious that there was something else going on,” says Courtney at Exencial. “That was probably one of the biggest proofs the market was short on liquidity and people who had been investing on margin and on borrowed money were having their loans called. Because not only were stocks down, gold was down, Treasuries were down. Everything was being sold to cash.”

Holding On

Friday 19 March: The week has been fast and furious and fatigue is writ large across the markets. Futures for the S&P 500 point to decent gains during trading in Asia and Europe, and stocks in both regions will end solidly up.

But the gush of headlines announcing central bank and policy action to counter the virus impact seems to slow, while the human and economic toll of the illness keeps growing. New York State orders all non-essential workers to stay home. Italy reports 627 deaths, the most in one day, as the tally in Europe’s epicenter tops 4,000.

That region is now talking about a recession as bad as 2009. In the U.S., executives at Bridgewater Associates estimate the country risks losing $4 trillion in corporate revenue on the back of the novel coronavirus without meaningful intervention.

“A lot of our clients see this as this happens once every 10 years or so we’re going to have a downturn and then the markets will recover and then we’ll set new highs,” says Courtney. “What’s unnerved a lot of people -- and we’ve gotten calls -- is how quickly this has happened.”

No one has any yard stick for a sell-off of this speed or a pandemic on this scale. In the end, the S&P 500 isn’t able to sustain a second day in the green. The gauge slides through the afternoon, ending the week 15% lower.

Meanwhile, the Fed expands its emergency program to help save the collapsing municipal bond market. And, despite all it has done so far, it’s also forced to say it will bolster swap lines with its peers to ensure dollar liquidity doesn’t freeze.

Finally, at long last, the never-ending week is ending. Ominously, after the central bank barrage, after the unprecedented government interventions, it finishes exactly the way it began -- with stocks down, bonds up and the dollar flat.

And the rate of infection of the coronavirus still accelerating.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.