Error Shackles Connecticut to a Debt Limit That Lawmakers Had Loosened

Connecticut Error Shackles State to Debt Limit Lawmakers Eased

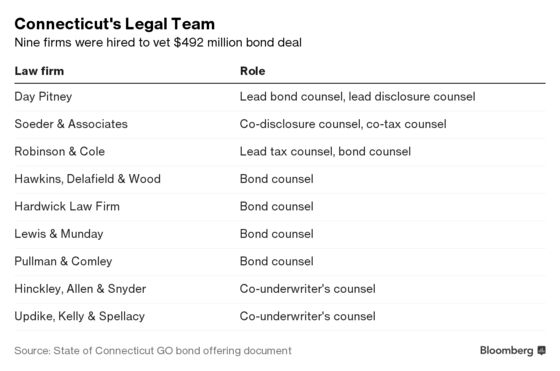

(Bloomberg) -- Nine law firms were hired by Connecticut and underwriter Bank of America Corp. to vet the state’s $492 million bond sale in June.

But none appear to have caught what could be a costly mistake: The contract effectively promises that Connecticut will stick to a strict $1.9 billion annual limit on a key type of debt sale, even though that cap was loosened by the state legislature.

That misstep, which stemmed from confusion in Treasurer Denise Nappier’s office about when the legislature’s step took effect, threatens to force the government to choose between saving money by refinancing debt or conserving its ability to fund public works with bonds backed by its general pledge to repay. It could also leave Connecticut facing a cash crunch if the economy lapses into a severe recession by curtailing its ability to sell short-term debt to cover temporary budget shortfalls.

“They’re going to have to watch their cash very carefully," said Marcia Van Wagner, a Moody’s Investors Service analyst. “If there’s a bad downturn or something happens where they need to draw liquidity, that becomes a real constraint.”

Connecticut is among the most financially strained states and for years has contended with budget shortfalls because the economy there has yet to replace all the jobs lost in the last recession.

The bond-timing error came after the legislature moved to give the state more flexibility by excluding refinancings and revenue-anticipation notes from the limit on general-obligation debt sales. Because the Treasurer’s office believed that change took effect in May when the legislation was enacted -- rather than in July -- the covenants in the June sale promised that there’d be no changes to the cap from May 15 until mid-2023. As a result, if Connecticut acts as lawmakers intended, it could be considered in technical default on the bonds.

In a Sept. 18 letter, Nappier blamed lawmakers for inadvertently amending the bill on the last day of the May legislative session to delay the effective date until July, unlike the earlier version that had it begin immediately. Benjamin Barnes, Governor Dannel Malloy’s Secretary of the Office of Policy and Management, said he was “extremely distressed" by Nappier’s failure to recognize that change.

“Your office and bond counsel failed to correctly read and interpret legislation passed this year leading to the issuance of bonds by the State that contain a covenant which, at best, is contrary to the will of the legislature, and at worst may harm the ability of future governors and legislatures to finance our capital program in a cost effective manner," he wrote in a Sept. 19 letter to Nappier.

Barnes asked the state attorney general to evaluate the impact of the covenant and to determine whether bond lawyers hired by Nappier were to blame.

Connecticut’s deputy treasurer, Lawrence Wilson, said the state still has the ability to borrow to contend with short-term cash shortfalls, if needed, through debt not covered by the bond cap, as it did in 2009 by drawing on a line of credit. But he said there’s no imminent need to pursue such options.

“Bond fund balances and issuance authority are expected to be sufficient for at least this fiscal year," he said. "Cash balances are at historic levels."

Lisa Morra, a spokeswoman for Day Pitney LLP, lead bond and disclosure counsel on the June sale, said "our advice and the treasurer’s actions were appropriate.” Spokespeople for the eight other law firms had no immediate comment or didn’t return messages. Selena Morris, a spokeswoman for Bank of America, didn’t return phone messages seeking comment.

Nappier said the drafting error may have the “salutary effect of keeping capital spending under tighter control," though she said she supports exploring legislative and judicial options for fixing it.

The most likely outcome of the mistake is curtailing Connecticut’s ability to do debt refinancings for the next five years, said Van Wagner, the Moody’s analyst. The rating company said the state issued a “substantial” amount of debt in 2012 that they won’t be able to refund until 2023, rather than 2022 when the securities can first be called back.

This isn’t the first time that Malloy and the treasurer have tangled over bond covenants.

Earlier this year, Nappier said a proposal by Malloy to stretch out payments to the state teachers’ pension fund to avoid a $5 billion increase in contributions by 2032 would violate parts of the contract for a $2.1 billion pension bond issue from 2008. The covenant in the pension-bond issue requires the state to appropriate the annual contribution to teachers’ pension for as long as the bonds remain outstanding to guard against underfunding.

Covenants “sound very responsible but there are unforeseen circumstances where a state needs to have some ability to make adjustments," Van Wagner said.

--With assistance from William Green and Danielle Moran.

To contact the reporter on this story: Martin Z. Braun in New York at mbraun6@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: James Crombie at jcrombie8@bloomberg.net, William Selway, Michael B. Marois

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.