China’s Plan for the Yuan Could Backfire in Any Crisis, Strategist Says

China’s Plan for the Yuan Could Backfire in Any Crisis, Strategist Says

(Bloomberg) -- China’s currency-swap lines with nations spanning the globe, designed to bolster the international role of the yuan, could backfire badly in a world crisis.

So argues Mansoor Mohi-uddin, a senior macro strategist at NatWest Markets in Singapore. The danger is that foreign central banks would exchange their currencies for yuan with the People’s Bank of China, then dump those holdings for dollars if a crisis hits, he wrote in a research note Friday.

“This would exert downward pressure on the yuan’s exchange rate against the greenback at a time when the PBOC would also likely be trying to shore up sentiment on its own currency,” Mohi-uddin wrote. Swaps “may be the yuan’s weakest link in a major financial crisis.”

Such an exchange would highlight how, though the yuan is now officially a reserve currency -- with the imprimatur of the International Monetary Fund -- its global appeal is well short of the dollar’s. China’s currency is used in 4.3% of global foreign-exchange transactions, against the dollar’s 88.3% share, according to the Bank for International Settlements.

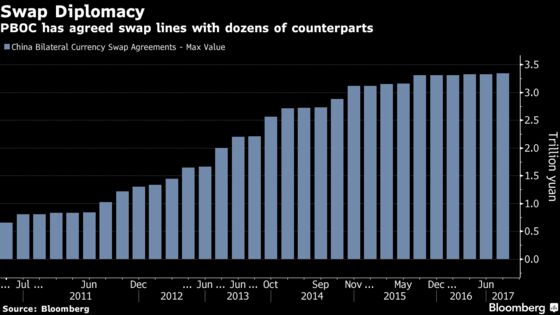

China has set up currency swap lines with dozens of countries to grease trade and, if needed, to act as an emergency backstop. NatWest calculates the total as a potential 3.7 trillion yuan ($523 billion).

Unlike the Federal Reserve’s swap lines with the euro region, Japan, Canada, the U.K. and Switzerland, the PBOC’s arrangements don’t require approval for activation, according to NatWest’s analysis. The PBOC didn’t immediately respond to a faxed question on the issue of approval to tap the swap lines.

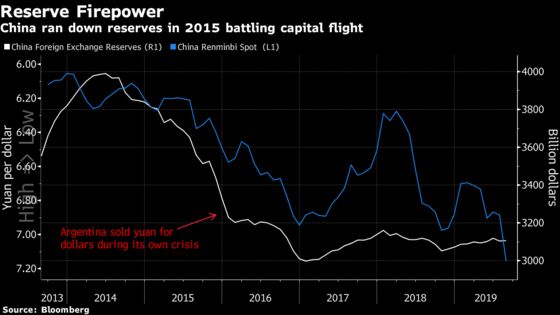

Transactions with Argentina a few years ago illustrate the risk. The South American country started accumulating yuan via its swap line with the PBOC in late 2014. Then in December 2015 it converted yuan into dollars, at a time when China was itself running down its foreign-exchange reserves as it battled capital flight.

China could always nix its swap lines to forestall any additional pressure on the yuan. But that would come at a cost, said Mohi-uddin, who’s been following currency markets for more than two decades.

“It could do that, but would then set back its long-term” goal “of getting the yuan to be a major-traded currency,” he said in an email.

--With assistance from Yinan Zhao and Claire Che.

To contact the reporter on this story: Christopher Anstey in Tokyo at canstey@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Christopher Anstey at canstey@bloomberg.net, Cormac Mullen, James Mayger

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.