China’s Credit Rebound May Spell Trouble for Huarong Investors

China’s Credit Rebound May Spell Trouble for Huarong Investors

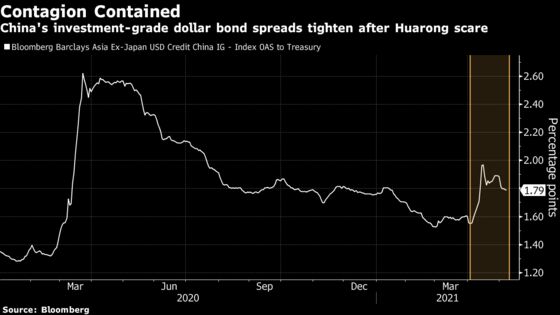

(Bloomberg) -- Market contagion surrounding China Huarong Asset Management Co. is fading less than six weeks after credit investors reeled at the prospect of a default by one of the country’s most important state-owned companies.

But while the tentative recovery is good news for Beijing’s attempts to instill more credit-market discipline without triggering a financial crisis, it could be a bad omen for any China Huarong bondholders still counting on a government bailout to make them whole.

Spreads on investment-grade dollar bonds have tightened after hitting a nine-month high at the height of the panic, and yields on offshore junk notes are lower than at the end of March, according to Bloomberg Barclays indexes. Tencent Holdings Ltd. recently secured $4.15 billion in one of Asia’s biggest dollar bond deals of the year, while Bank of China Ltd. units raised the equivalent of $2.35 billion in a multi-currency bond sale. At least ten Chinese borrowers were marketing or have sold dollar bonds this week, leaving the period set to be one of the busiest this year.

The same is true of other indicators of stress in China’s financial system. While rising corporate defaults spilled over to the country’s money markets in November, there are no such signs of concern now. Banks are having no trouble borrowing from each other, judging by the declining cost of one-year interbank debt. The overnight repo rate fell below 1.5% last week for the first time in two months.

Some market watchers say the relative calm could embolden Beijing to impose losses on China Huarong’s creditors.

“Markets are getting a signal as loud and clear as one blasted from loudspeakers: China’s policy stance of ‘no debt guarantees’ has been extended beyond local government SOEs to large, national-level SOEs,” DBS strategists led by Taimur Baig wrote in a May 3 note. “Markets should know that these are not mere platitudes, if Huarong serves as an example.”

Reducing moral hazard has become a priority for President Xi Jinping as he seeks to make the nation’s state-owned companies more efficient and better run. Ensuring the equity and bond markets reward and punish firms for their corporate behavior, rather than relying on the cumbersome state system, is a relatively new approach. There are signs it is working. SOEs have replaced their private counterparts as the country’s biggest source of defaults.

Allowing a debt restructuring at China Huarong, one of the country’s biggest financial conglomerates, would send a strong signal of the government’s resolve. The company’s dollar bonds due 2025 traded at well above par at the end of March, despite the trial and swift execution of its chairman Lai Xiaomin in January for bribery. They’re now priced at about 80 cents on the dollar. Recent high profile defaults by two university-linked companies, Peking University Founder Group Corp. and Tsinghua Unigroup Co., have served as additional warnings to investors dabbling in borrowers with ambiguous ties to the state.

Even after the rout in China Huarong’s bonds, some investors are still betting Beijing will stand behind the company. It has so far met all of its debt obligations on time and has said it is operating normally with sufficient liquidity. A China Huarong vice president recently said downgrades by international rating agencies “have no factual basis” and are “too pessimistic.” The comments, which were carried in the state-run Shanghai Securities News, were viewed by some observers as a signal of continued state support.

The nation’s banking and insurance regulator has also said China Huarong has ample liquidity, though it has yet to provide clarity about the company’s future or what penalty bondholders might pay, if any, to help fix its debt issues.

| For more on China’s credit market |

|---|

|

Curtailing implicit guarantees won’t be easy for China, given that they also backstop the nation’s stocks and currency. But there are signs of a broad shift. The “national team” of state-backed funds has become less influential in the equity market, while China allowed the yuan to weaken past the key support level of 7 per dollar in 2019 for the first time in more than a decade.

Of course, there’s no guarantee that credit markets would remain calm if China Huarong announced a restructuring or default. Given the firm’s sprawling and complex business, investors have little clarity over how such an event might ripple through China’s $54 trillion financial system. And because China Huarong hasn’t released its 2020 financial results, the state of its balance sheet remains a mystery.

Still, the fact that signs of a broader credit-market panic have subsided without major intervention from Beijing are likely to be of comfort to officials seeking to tackle China’s moral hazard problem.

“It is a success as good as can be for policymakers, without using a heavy-handed approach,” wrote the DBS strategists.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.