The Chinese IPO That Led the Way in Wall Street’s Virtual Shift

The Chinese IPO That Led the Way in Wall Street’s Virtual Shift

(Bloomberg Markets) -- When Ma Cunjun strapped on his face mask and boarded a nearly empty flight to New York from Hong Kong, the most important deal of his life was at risk of unraveling.

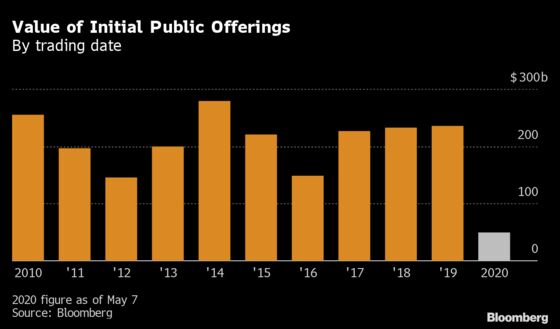

It was Jan. 29, and in less than two weeks Ma was supposed to take his Shenzhen, China-based online insurance platform public on the Nasdaq stock exchange in New York. Preparations for Huize Holding Ltd.’s initial public offering, which in September had targeted $150 million, had been in the works since 2018. But now China’s coronavirus outbreak was bringing Asia’s largest economy to its knees and threatening to cause havoc around the world. Ma, 48, had to decide whether to push ahead.

His bankers were offering conflicting advice. Morgan Stanley was suggesting a delay, arguing Ma’s company should wait to report a full year of earnings. Shortly after the founder and chief executive officer arrived in New York, Chinese share prices suffered their biggest one-day tumble in almost five years. But Citigroup Inc. was saying the window for a deal was still open—if Ma was willing to raise less money, cut the valuation, and move quickly.

On a Feb. 3 conference call, with Ma dialed in from the Manhattan Club hotel and many of his bankers joining from their home offices, he gave the green light. The next week would be a race to complete one of the world’s first all-virtual IPOs, a deal that’s since become a template of sorts for stock market debuts in the age of coronavirus. “We were asking ourselves a lot of questions regarding what was going to be the probability of success,” says Bruce Wu, the Hong Kong-based banker who led the Huize offering for Citigroup, where he’s worked since 1994. “Once we made that judgment call, it was full steam ahead.”

Citigroup bankers—Morgan Stanley, having disagreed about the timing, had by now resigned from the offering—started dialing institutional investors across Asia and the U.S. that had shown interest in the 14-year-old platform, which makes money by taking a cut from helping sell life and health coverage for insurance companies. In-person meetings were out of the question, even in New York, where a lockdown wouldn’t begin until the following month: Ma says he was self-isolating in his hotel.

By this stage, the coronavirus death toll in China was inching closer to the scale recorded during the global SARS outbreak almost two decades earlier—and would eclipse it before the roadshow ended on Feb. 10. On Feb. 2 the U.S. had closed its borders to foreigners who recently visited China, and governments everywhere were tightening quarantine rules. Fortunately for Huize’s prospects, the Nasdaq seemed immune to the gathering storm, climbing to new records.

With his team of IPO bankers and Huize executives, Citigroup’s Wu mapped out the first entirely digital roadshow of his more than two-decade-long banking career. They put together more than 30 telephone and videoconference calls over four days, packing in work that would usually have taken six days and numerous flights. In one particularly intense 60-hour stretch, Ma held 15 back-to-back calls with investors in China and elsewhere. “It was a huge challenge physically,” he says. “I’m just glad that I work out regularly. Otherwise, it would have been very tough to maintain a clear mind.”

Needless to say, many of the merits of in-person meetings were lost: How do you read a room or decipher clues from a participant’s body language? In this instance, Ma’s team focused on investors who were familiar with the insurance industry and knew him or his company, at least by reputation.

In the end, the deal was oversubscribed by about two times and the offering upsized by 600,000 shares, a mild success. It priced Feb. 11 in the middle of the range and raised $55 million, about a third of the amount targeted in the September filing.

By the end of March, Huize’s share price had dropped 23%, along with declines in the handful of Chinese companies that listed on the Nasdaq following the virus outbreak. By April, Chinese listings on the exchange had largely dried up. The index had collapsed by as much as 30% at its low point on March 23. Investor sentiment was hammered further after an accounting scandal at Luckin Coffee Inc., a Chinese challenger to Starbucks Corp.

Ma seems unfazed by all the turmoil. “After listing,” he says, “we’ve received a lot of interest from institutional investors. Looking back, I think we were a bit too conservative.”

In Hong Kong, investors have been even more stoical. Chinese biotech companies InnoCare Pharma and Akeso Inc. made their debuts on the Hong Kong stock exchange in March and April, respectively, after the World Health Organization declared the spread of coronavirus to be a pandemic as it ripped through the U.S. and Europe, sending markets swooning. Both offerings priced at the top of their proposed ranges, with shares snapped up by a long roster of cornerstone investors; 12 such investors absorbed about 60% of InnoCare shares on its launch.

Like Huize, the InnoCare IPO was buffeted by the coronavirus. The Beijing-based company, which develops treatments for cancer and autoimmune diseases, postponed plans to sound out investors in early February as markets grew volatile and restrictions on travel to and from China made it harder for bankers, investors, and company executives to meet.

A month later, the spreading virus had dramatically altered the math for InnoCare’s bankers, including Morgan Stanley. On March 11, with U.S. markets in free fall, Morgan Stanley dealmakers sat through more than a dozen conference calls involving company executives and investors. On the first day, Morgan Stanley sealed commitments that went beyond the planned issuance, says one banker familiar with the deal. The team worked from 9 a.m. until midnight, talking to twice as many investors as they’d tap during a regular day, the banker says.

Adjusting to the new realities, a relentless schedule of meetings that followed the sun from Asia to the U.S., was crucial in reducing market risk, says Shane Zhang, co-head of Asia-Pacific investment banking at Morgan Stanley. “We shortened the marketing window,” he says, “but were able to facilitate more meetings per day.’’

Virtual dealmaking may outlast the virus in an industry that’s long mythologized the handshake. Travel and entertainment expenses will shrink, and bankers will find they can seal deals from the comfort of their living rooms, without battling jet lag and spending so much time on the road. Meanwhile, investors and clients are becoming more attuned to pitches made over videoconference, though there will always be some business that’s best done in person.

For Ma, the Nasdaq building in Manhattan’s Times Square had a distinctly impersonal feel on Feb. 12, the day of Huize’s listing ceremony. Flying to New York just four days before the U.S. tightened immigration procedures had paid off for him. But other Huize executives and Citi’s Asia team weren’t so lucky: The exchange barred entry to anyone who hadn’t been in the country for 14 days.

This day was the culmination of a journey that began for Ma in the 1990s when he started as a 24-year-old with a Shenzhen-based unit of Ping An Insurance (Group) Co., China’s largest insurer by market value. Dressed in a sapphire blue suit with a bright red scarf around his neck, Ma stood alone in front of the giant Nasdaq screen in anticipation of the iconic bell-ringing ceremony.

The experience left him with mixed feelings of regret and satisfaction. “Of course it was a pity that I was the only person representing the company at the IPO,” he says. “But the fact we were able to go public during such a trying time was no easy matter.”

Chen covers asset management for Bloomberg News in Hong Kong, where Chan covers investment banking and Fioretti equity markets.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.