Tycoon Behind a Crisis-Era Property Crash Now Sits on a $9 Billion Debt Mountain

Property tycoon Cevdet Caner crashed and burned in 2008. Now he's linked to a famous German landlord – with $9 billion on line.

(Bloomberg) -- The email lit up inboxes at six of the world’s biggest banks.

A wealthy businessman by the name of Cevdet Caner, the anonymous sender wrote, seemed to be headed for trouble.

Or rather, headed for trouble again.

The email warned that Caner had spun a complex financial web to profit from a big German real-estate concern in which his family held a major stake — at other investors’ expense. Hedge funds, meanwhile, were taking aim at the company, Adler Group SA, whose expansion had been funded by a Who’s Who of global finance.

Before long, Barclays Plc, Deutsche Bank AG, Goldman Sachs Group Inc., JPMorgan Chase & Co., Morgan Stanley and UBS Group AG were all looking into Adler, one of Germany’s biggest home landlords, according to emails seen by Bloomberg News. More, Adler’s stock price was starting to tank — good news for the shorts betting against Cevdet Caner.

That 12-page email, sent by a former Caner associate last March, offers but one clue to the intrigue now swirling around Adler and the man once characterized as its “undercover boss.”

Caner, in a statement to Bloomberg, says the email is part of a smear campaign designed to manipulate markets. Adler says similar and adds that its relationship with its banks is as strong as ever. Representatives for the banks declined to comment.

But the questions won’t go away. Adler today owes its creditors more than 8 billion euros ($9.3 billion). Bears warn it might be more leveraged than it appears. Adler’s stock and bonds slumped on Wednesday after short seller Fraser Perring published a lengthy report accusing it of being “built on systemic dishonesty,” sending the shares to the lowest on record and forcing its largest shareholder to strike a deal with a rival. Even German politicians want answers. Just how did Adler cut its deals — and just who stood to benefit?

The story of Cevdet Caner winds across Austria and Germany, through the City of London and into some of the world’s richest banks. It’s an uneasy tale for an era of easy money, befitting a season of debt-driven deals, obliging bankers and overlooked risks.

For most of the 141 years since its founding in Frankfurt, the Adler company enjoyed a history of quiet distinction. It turned out some of Germany’s first factory-made bicycles. It got into automobiles not long after Mercedes-Benz. In the Hollywood horror classic “The Shining,” Jack Nicholson obsessively types “All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy” on an Adler typewriter, said to be director Stanley Kubrick’s machine of choice.

Then Adler abandoned manufacturing for the heady heights of real estate. About a decade later, Caner showed up and Adler started its transformation into a major player in the German market.

He’d been there before. Only 13 years ago his Level One real estate group buckled under debts of 1.2 billion euros. The collapse prompted a long, acrimonious investigation into Level One and Caner’s role in the debacle. It wasn’t until 2020 that he was acquitted in Vienna on criminal charges of conspiracy, commercial fraud and money laundering — charges he’s long maintained were instigated by business enemies. He says hedge funds brought down Level One and want to bring down Adler, too.

This much is sure: the clock is ticking. Adler has become a major landlord in a country of tenants. It owns 70,000 apartments across Germany, including 20,000 in Berlin, the fast-gentrifying capital where soaring rents have prompted calls for radical solutions. It also has about 600 million euros of debt coming due in the next six months. It must pay off that debt or persuade banks to refinance it.

Adler has yet to draw on a 300 million-euro revolving credit facility arranged in March, according to its financial filings. That gives the company wiggle room should bond investors balk. The company also says it could borrow about 1 billion euros against its property on the bond markets.

But markets are markets, and hedge funds sniff out weakness. Perring’s Viceroy Research accuses Adler of conducting a string of transactions where the company sells to a related party at an inflated price that is never settled in full. The company, it says, artificially marks up its balance sheet with unrecovered receivables. It also accuses Adler of working in concert with undisclosed related parties to buy controlling stakes in asset-rich companies, breaching disclosure obligations.

Adler, in response, said the report contained many false allegations and that the value of its real estate assets has been determined by independent appraisers and confirmed by financing banks. Over the past 12 months, the company said it sold multiple portfolios with prices above the values in its books, and that it’s received approaches from institutional investors who want to buy large parts of the portfolio. “Adler is assessing such approaches as part of its ongoing review of strategic options,’’ the company said. “Therefore, contrary to the report, no default under notes issued by Adler or any of its subsidiaries has occurred or is continuing.” Adler has said it will publish a more detailed response soon.

Adler's portfolio is valued at 12.6 billion euros and it has net assets of 4.95 billion euros, according to the company's most recent earnings. By contrast, its market capitalization is just 1.4 billion euros, meaning it trades at a wide discount to the reported value of its properties. As such, a major asset sale at or close to book value would help ease any refinancing pressure. Recent sales of German housing portfolios -- including a 9.1 billion-euro acquisition of several German and Nordic properties by Heimstaden AB last month -- have underlined the red hot demand for apartments in the country. Scope Ratings affirmed the BB credit rating for Adler’s main unit in an update published Sept. 29.

Still, German watchdog Bafin said it was taking Viceroy’s report seriously and was examining the allegations. If that gives rise to any suspicion of crimes, Bafin said it will file a complaint to the relevant prosecutors.

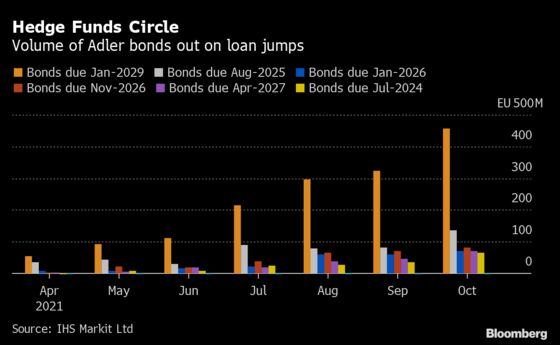

Even before Viceroy’s accusations were made public, the cost of insuring Adler debt against default had skyrocketed to record levels. Gladstone Capital Management LLP and other hedge funds have disclosed they’re shorting Adler stock. Other hedge funds are betting against Adler bonds, according to people familiar with the matter. Some credit traders at JPMorgan in London recently bet against Adler, too, only months after a different unit of the U.S. bank helped underwrite more bonds for the company.

“Investor confidence in Adler Group has deteriorated,” BNP Paribas SA analyst Chris Kay wrote in a note to clients on Sept. 15. “Confidence is now more important than ever for funding the business model moving forward.”

With the shares accelerating their decline in the last weeks, triggering some margin calls, Adler on Oct. 4 announced that it’s exploring potential asset sales as a means to reduce its leverage. Late on Thursday, Adler's largest investor — Aggregate Holdings, a company informally advised by Caner — sold a call option for about half of its stake to rival Vonovia SE. As part of the transaction, Aggregate said it was repaying an outstanding margin loan.

In his warning to the banks, Caner’s former associate paints an unflattering portrait of murky business connections, complicit associates, secretive trusts, complex cross holdings and more. Caner’s connections to Adler, for instance, involve at least a dozen separate entities in six different jurisdictions, including Monaco, his home base, the sender says. Bloomberg obtained a copy of the memo on the condition that it not identify the author.

A key issue is how Adler came together via a complex three-way merger. In late 2019, Adler acquired an Israeli company that owned a big stake in another German real-estate company, ADO Properties, which was financially stronger than Adler. Five days later, ADO Properties announced that it was buying its new part-owner, Adler, as well as a stake in a third real estate company, Consus Real Estate, that was controlled by Aggregate. The combined company was rebranded Adler Group.

At the time of the deal, the web of connections between Caner and Adler wasn’t widely known. The links and the related party transactions that helped fuel investor concern are disclosed in public filings in countries including Luxembourg, Germany, the U.K. and Monaco.

Still, local media soon started to pick up on the man who appeared tied to all those companies. Minority shareholders protested, saying ADO was paying the bill for a transaction to fix the balance sheet of Adler and Consus. Last month, after Germany’s political party Die Linke, or The Left, started asking about the deal in parliament, Adler issued a statement saying it has always provided “full transparency.”

Through his lawyer, Caner says he’s never sought to hide his investment in Adler and disputed the notion that he’s calling the shots. He insists the company is run by its management.

“Nevertheless, as an active advisor to his family investments in Adler Real Estate AG from 2012, Mr. Caner has provided his views and input on the optimal development of the company which is today Adler Group SA,” the lawyer wrote. “Such contribution is not different to the various institutional and private investors or bondholders who actively provide remarks, recommendations and advice to the companies they are invested in or those companies where the funds they advise invest.”

Even detractors admire Caner’s charm, self-assurance and penchant for complex business and finance. He’s known to fete bankers at the Grill Royal, a Berlin power spot where 100 grams of Kobe beef fillet will set you back 150 euros. He’s a regular in Cannes, on the yacht-and-champagne circuit. He splits his time between Monaco and homes in Berlin, New York and London.

It wasn’t always this way. One of seven children born to parents from Turkey, Caner grew up in Linz, Austria. He studied business there and, for a time, pursued political ambitions as chairman of the young Socialists. He first rose to prominence in business with CLC AG, a call-center company he founded at the age of 22. He left in 2002. Two years later, CLC went broke, which Caner blames on a change of strategy after his departure.

Caner next turned to real estate. Level One Group grew to include more than 200 business units in Germany, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg and Jersey that mainly invested in Communist-era public housing. It was financed mostly with loans from Credit Suisse Group AG, ABN Amro Bank NV and Bear Stearns Cos., about half of which were packaged into securities during Wall Street’s subprime securitization craze. When the bubble burst, so did Caner’s grand plans. Level One collapsed, owing creditors a combined 1.2 billion euros. It was Germany’s biggest real estate blow-up in 15 years.

In London, Caner’s financial troubles hit the tabloids when his 20 million-pound (then $31 million) townhouse in Mayfair was repossessed.

“Mr. Caner lost significantly more than just an office in Mayfair,” his lawyer, Ben M. Irle, wrote in a statement. “He lost significant financial wealth, he lost more than a decade in courts to be proven non-guilty, he lost irreversible precious time with his family, he lost against the public judgment led by the media who judged him on wrong grounds, among many other losses.”

Yet within a few years, Caner was back. In 2012, while still entangled in the Level One debacle, he began investing in Adler. His first move came through his family trust, Caner Privatstiftung, registered on the historic main square of Linz. The foundation bought Mezzanine IX Investors LP, a Texas company that held a controlling stake in Adler. The foundation later sold that stake to Caner’s wife, her brother and a business associate from the Level One days.

Ties between Caner and Adler kept growing. In 2016, the Austrian Takeover Commission accused Adler, Caner and others of working in concert to acquire a controlling stake in a rival landlord, Conwert Immobilien Invest SE, without tabling a formal bid, as required by law. Conwert management described Caner as Adler’s “undercover boss”; Caner downplayed his role, saying he had “natural authority” given his family’s stake in Mezzanine IX and its stake in Adler. The European Court of Justice ruled last month that the takeover commission had overreached in the case.

Still, a statement from Caner welcoming that September ruling represented a rare public acknowledgment of his interest in Adler. Previously, company bond prospectuses had only mentioned him in small print, citing potential legal risks in Austria. Rules introduced in Luxembourg in 2019 prompted the disclosure of his wife’s stake in Mezzanine IX and, by extension, Adler. Asked by German tabloid Bild in March 2020 whether Caner had a direct or indirect stake in the company, Irle, his lawyer, told the newspaper that Caner didn’t.

And as recently as September, CreditSights senior analyst David Shnaps said that Adler’s investor relations team told him Caner’s role was limited to merger advice, and that he didn’t have a direct or indirect interest in the company.

Irle told Bloomberg that “the shareholding structure was at all times published and disclosed, being part of numerous public documents, notably prospectuses, hence never hidden from anyone. The fact that family members of Mr Caner are invested in Adler does not make Mr Caner — directly or indirectly — a shareholder in Adler.”

After all the deal-making, Adler is levered up. Its debts are equal to 55% of the value of its properties, significantly higher than most of its peers.

But even that may understate Adler’s debt load. Among its assets are more than 1 billion euros of accounts receivable. Companies typically only book a receivable if they expect to get paid within 12 months. Adler has accounts receivable tied to asset sales from as long as three years ago, a fact it attributes to the nature of long-term real estate developments. The company says it has followed pertinent accounting rules and that KPMG has reviewed its books.

Among that 1 billion euros is 209 million euros that Adler is still owed from the 2019 sale of a stake in a Duesseldorf development project. The buyer who owes Adler the money: a Berlin-based company owned by Caner’s brother-in-law. Adler disclosed in August that it would cancel the deal and bring the development back on its own balance sheet.

“Booking receivables on your balance sheet that are in some cases years old is very aggressive, and it’s certainly not something that’s done at any other real estate company that I know of,” said Shnaps, the CreditSights analyst. “The fact that it does this makes you want to turn over more rocks and begs the question, where else are they being aggressive?”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.