Pandemic Profits Show Why Stock Bulls Ignore Old-School Accounting

Pandemic Profits Show Why Stock Bulls Ignore Old-School Accounting

(Bloomberg) -- The higher stocks go, the louder the forecasts for their demise. Prices are hopelessly stretched, warn the naysayers -- the gains aren’t justified by earnings.

But to a growing number of investors, the problem isn’t bloated valuations. It’s that longstanding accounting standards misclassify billions of dollars of cash-cow assets as if they’re drags on businesses.

Consider a company like Johnson & Johnson, whose value has swollen by almost $140 billion since March 2020 thanks in part to the success of its coronavirus vaccine. While investors have enthusiastically rewarded J&J’s formidable profit machine, bookkeeping rules perversely turn the engine of its earnings power into one of its biggest headwinds. Buried on the income statement of its most recent earnings release was a huge expense item: $3.4 billion for R&D. If it had been as an investment rather than simply a cost, the profit would have nearly doubled.

The accounting standards now viewed by some as a pointless hindrance in determining stock values first began as an effort to reform corporate reporting following the 1929 stock market crash. Rules first published in the late 1930s evolved into the Generally Accepted Accounting Principles in use today.

The problem is that the rules developed to track steelmakers’ businesses don’t always work in an economy where intellectual property reigns.

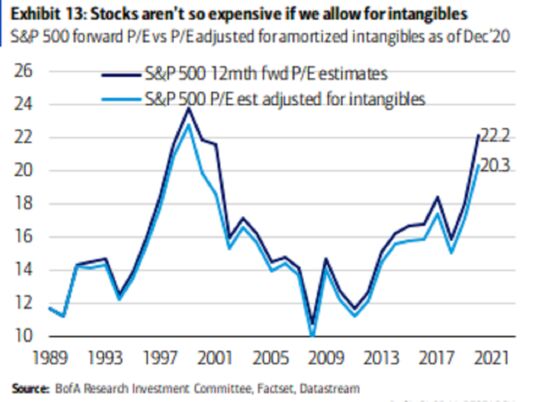

If spending on intangibles such as research turned into assets whose costs were spread out over three to five years, current profits from S&P 500 companies could increase by 10%, according to an estimate by Alger, an investment management firm that uses R&D as a measure of innovations to pick stocks. If nothing else, the adjustment could help rationalize indicators like price-earnings ratios, valuation metrics that at first blush make the U.S. stock market seem overpriced.

“The market is doing the right thing” by looking past earnings in their conventional form, said Brad Neuman, director of market strategy at Alger. “One of the reasons why the P/E looks higher today is because there’s much more intangible investment, which is weighing on earnings.”

Last year, 46 companies in the S&P 500 posted net income that was smaller than their R&D outlays, an amount only eclipsed twice in the last decade, data compiled by Bloomberg show. While most were companies that saw organic earnings crushed by the recession, a larger number of firms posted a similar deficit in 2016 and 2018.

Changing the rule to reflect market practice would enhance profits -- in some cases, turning losers into bottom-line winners -- and perhaps better focus managers on the seemingly sensible goal of attending to growth in the future.

Twitter Inc. lost $1.1 billion in 2020, in part because of a 28% jump in R&D to $873 million, as the social media company invested in rolling out new tools and products to keep users engaged. Merck & Co.’s $13.6 billion in R&D -- which included higher costs for clinical and drug development amid a global pandemic -- was almost double the $7.1 billion of income generated last year.

Is there direct evidence investors are making the adjustment on their own? No. But various facts can be marshaled to suggest they are. One is simply the market’s above-average rate of return since the financial crisis - nearly 20% a year - which results in a stubbornly high valuation. One interpretation of the high P/E is that investors believe standard accounting underestimates real-world earnings.

A study by Bank of America Corp. strategists including Jared Woodard showed the S&P 500 would be about 10% cheaper than it looks should some intangibles be adjusted. A separate analysis from Valens Research, a boutique investment research firm that focuses on accounting analytics, showed similar results.

“The markets are actually pricing in not that aggressive growth, and also pretty reasonable profitability when we see through the accounting noise,” said Rob Spivey, director of research at Valens Research. “There’s this huge asset that’s sitting on corporate balance sheets that people are just totally missing.”

The distortion also matters to a raging debate on where the economy is heading. The fact that spending on software and R&D is listed as expenses means anyone who follow corporate data for guidance on capital investment would under-appreciate one big source of 2022’s growth engine, according to Cornerstone Macro LLC economists led by Nancy Lazar.

“S&P data way understate tech capex’s footprint because they do not include R&D or software,” the economists wrote in a note this month. “Capex will drive this cycle,” they added, “once and for all putting an end to the secular stagnation narrative.”

Accounting rule makers are taking notice. In June, the Financial Accounting Standards Board sent out a letter to the financial community seeking feedback on how the recognition, disclosure and measurement of intangible assets can be improved.

Wall Street isn’t waiting for the accountants to figure it out. To help enhance the performance of value investing, firms like UBS Group AG have developed ways to take into account intangibles such as R&D and corporate branding.

One example of a hidden gem, according to the UBS model, is Nordstrom Inc., a retailer whose shares have almost tripled in the past year. At 20 times reported book value, the stock ranked among the most expensive in the Russell 3000. Yet when the worth of brand name, innovation and corporate efficiency is considered, it sat in the cheapest quintile, UBS data show.

“The role of internally developed intangibles has come to the forefront with many arguing that traditional book to price ignores the value of branding, innovation and efficiency,” UBS analysts including Jaiwish Nolan wrote in a recent note. “Our initial analysis finds this enhancement presents investors with the opportunity to find stocks that may be mis-valued.”

Experts differ on what constitutes an intangible asset and some warn that their rise is not all good news. Be it a blockbuster video game or a formula for a life-saving drug, while the original may be expensive to produce, duplicating it is often cheap. That means strong economies of scale that often drives rapid growth. On the flip side, a new idea could quickly render the old one obsolete, leading to a rapid decline in business.

Michael Mauboussin, head of consilient research at Morgan Stanley, studied sales patterns for Russell 3000 companies between 1984 and 2020 based on their intangible asset intensity. He found that intangible-heavy firms tended to grow faster, but with greater volatility.

“Intangible assets are rarely standard, unlike tangible assets, which means they have limited salvage value,” Mauboussin wrote in a report in June. “A company with obsolete software cannot get much for it, while a company with a failed store can recoup some value by selling inventory and furnishings. This means that we should also expect to see slower growth rates, or a greater rate of decline, for the losers.”

Innovation has increasingly become a key differentiating factor for winners and losers. Using the ratio of R&D investment versus revenue to measure innovation, Alger found that biggest spenders have outperformed the bottom ones by 1 percentage point annually over the past 45 years. Over the last decade, the gap has widened to 5.6 percentage points a year.

The gravitation toward ideas and away from physical capital has accelerated during the pandemic, and that fed into business actions. Last year, intangible investments from Russell 3000 companies totaled $1.8 trillion, more than double the amount they spent on capital expenditures, according to an estimate from Morgan Stanley.

As a result, the market has never traded at such a premiums to its physical assets. The S&P 500 is now about 15 times its tangible book value, a record multiple that’s close to double the dot-com peak, data compiled by Bloomberg show.

With R&D treated as a cost of doing daily businesses, rather something that has future value, anyone who follows current accounting standards is likely to misjudge stock opportunities, according to Alger’s Neuman.

“It throws off your earnings. It throws off your valuation,” he said. “I’m very confident that over the long term, much of this will be capitalized and accounting will catch up with the economy, but it’s going to be a little painful for the next several years.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.