Bond Traders Have Three Choices in This ‘Fed End’ Market

Bond Traders Have Three Choices in This ‘Fed End’ Market

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The world’s biggest bond market has reached what I’m calling a “Fed end.”

Yes, the Federal Reserve left open the possibility for another interest-rate increase in 2020 or 2021 after its meeting on Wednesday. And yes, policy makers could put a hike back in play for later this year if the economic outlook brightens. But Chairman Jerome Powell went out of his way to emphasize that monetary policy is “in a good place” and that the next move in rates could be in either direction. As Bloomberg News’s Liz Capo McCormick was quick to point out, history suggests it’s going to be a cut, no matter what Powell says.

Predictably, investors in the $15.8 trillion Treasury market bought everything in the wake of the Fed’s dovish surprise. Some of those decisions will prove to be hasty, as Jim Vogel of FTN Financial Capital Markets wrote succinctly in a note. “The first fixed-income mistake to avoid the rest of this month is to believe the market has rationally priced in the next 4-6 months,” it said. “The market is simply guessing.”

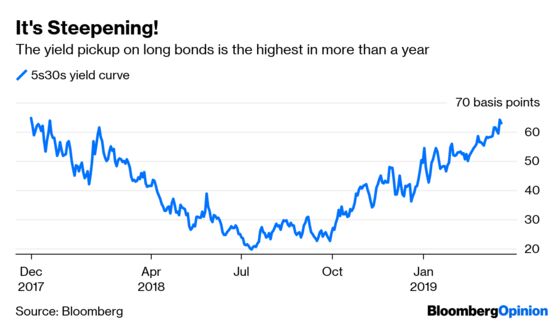

Sure enough, some yield curves reached the flattest levels since 2007 while others became the steepest in 15 months. What this boils down to is the three basic types of bets that investors can make in Treasuries:

- Buy short-term bills.

- Buy intermediate (two- to seven-year) notes.

- Buy 10-year notes or 30-year bonds.

Let’s start with bills. The clear appeal to hiding out in short-dated government debt is obvious just from looking at the prevailing yield levels after the Fed’s decision. The rate on six-month bills (2.48 percent) is higher than yields on Treasury notes from two to seven years, and it’s not that close. Every yield curve involving those maturities is inverted by the most in more than a decade.

This would be a winning wager if U.S. growth picks up again later this year and the Fed puts more rate hikes back in play. The risk is that the economy takes a turn for the worse and that yields fall even lower, forcing traders to reinvest at lower rates than if they had simply bought longer maturities now.

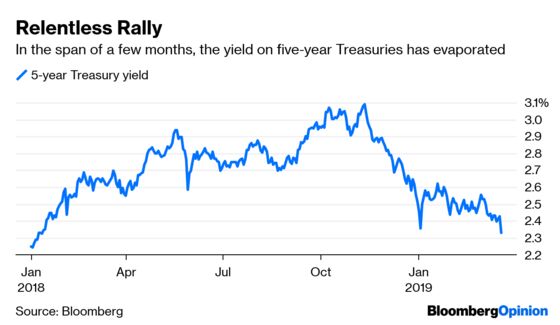

This sort of fear, of course, is why five-year Treasury yields tumbled by a whopping 10 basis points on Wednesday, one of the biggest daily declines in recent memory. It’s not hard to imagine a situation in which the current 2.25 percent to 2.5 percent range for the fed funds rate is as high as it goes, and at some point in the coming years a recession causes the central bank to drop it back toward zero. In such a scenario, locking in a 2.32 percent yield from now through early 2024 seems like a no-brainer.

The hard part, as always, is knowing exactly when that sort of downturn would occur. That explains why even though many parts of the curve are reaching new highs or lows, the yield spread between three- and seven-year notes is hovering right around its 2019 average. Similarly, the difference between five- and seven-year yields is near its average over the past 12 months.

For investors who simply want to give in and take a maximum bullish stance, the 30-year bond clearly looks good on a relative basis, even if the absolute yield is underwhelming at 2.96 percent. The bond represents a 64-basis-point yield pickup compared with five-year notes, about the most since December 2017. History suggests the curve has room to steepen further, but probably only if short-term yields are falling faster than long-term ones. In such an environment, owning high-duration assets would provide the largest profits.

Of the three paths, which route to take is truly a tough call, in no small part because the Fed has lost a lot of credibility with its rapid shift over the past few months. I agree with Bloomberg News’s Richard K. Breslow, who said of the central bank’s latest decision: “Don’t listen to the Monday morning quarterbacks try to tell you that it makes perfect sense.” It was quite shocking that policy makers abruptly chose to give up the option to raise rates again this year.

Powell appears to be trying to shift subtly what “neutral” means, noting that the central bank’s “overarching goal” is to sustain the economic expansion. In a way, that flies directly in the face of how Janet Yellen described neutral: a level of interest rates that is neither expansionary nor contractionary for the economy. Growth was always likely to be slower this year compared with 2018 as the boost from fiscal stimulus waned. It’s questionable to suggest that the slow-but-steady climb in short-term interest rates was responsible for weakening the economic outlook. And I’m skeptical that pausing now will suddenly revive inflation.

It’s certainly hard to get excited about Treasuries after this week’s repricing, perhaps explaining why riskier segments of fixed income are on fire. At Pacific Investment Management Co., the firm that pushed the idea of lower-for-longer interest rates, Joachim Fels and Andrew Balls say they’re “broadly neutral on duration and maintain a modest curve steepener in the U.S.” That seems about right.

For now, the answer might be walking between paths. The yield pickup for buying a two-year Treasury note and a 10-year note, while selling two five-year notes, is the highest since 2013. That seems like a decent way to express that the outlook from here has become anyone’s guess — Fed officials included.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.