Bond Traders Are Paid Big to Dump U.S. Treasuries and Go Abroad

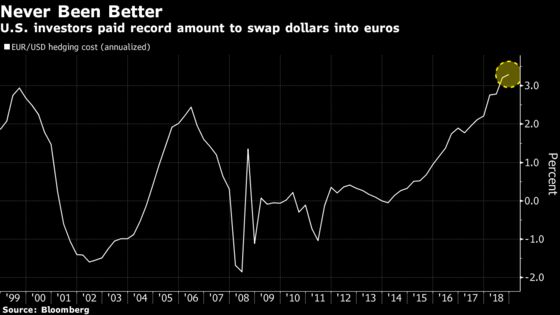

Dollar investors are getting paid more than ever to enter a trade that takes the currency risk out of their euro-based returns.

(Bloomberg) -- There’s never been a more profitable time for U.S. investors to ditch Treasuries and go abroad.

By now, everyone knows Treasuries have been a lousy bet. But because of a quirk in the way currency markets work, there’s even less reason for investors to park their money in U.S. government bonds. Those with dollars to spare can lock in historically high returns in Europe and Japan, even though yields in the two markets are among the lowest in the developed world.

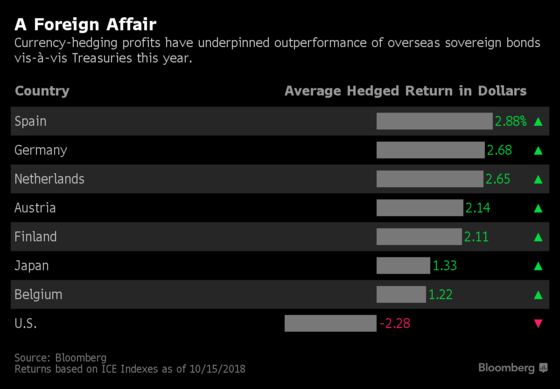

In fact, dollar investors are getting paid more than ever to enter a trade that takes the currency risk out of their euro-based returns. As a result, they can earn what amounts to 3.8 percent a year from ultra low-yielding 10-year German bunds -- more than a half-percentage point above Treasuries. Aside from Italy, hedged U.S. investors would have done better putting their money into the bonds of any developed nation this year rather than Treasuries.

“These low-yield bonds pack a pretty big punch after hedging,” said Jim Caron, a fund manager at Morgan Stanley Investment Management, which oversees $474 billion. Caron is using the strategy to buy euro bonds and highlighted Spain, where he can get effective yields of nearly 5 percent on 10-year notes. That compares with roughly 3.2 percent for comparable Treasuries. “We do this across all of our portfolios. This is a lucrative quirk.”

But more than just being a savvy trade idea, it underscores how the longstanding and popular narrative of the U.S. as a go-to destination for yield-seeking bond investors is little more than an illusion.

Less Than Zero

The reason is simple: The trade cuts both ways. While U.S. investors have few incentives to stay at home, the sky-high cost for foreigners to hedge the dollar means they have little cause to buy Treasuries. In some cases, their effective yields can fall below zero. Any letup in demand could drive up U.S. borrowing costs, at a time when the government can ill-afford to lose investors as it raises ever more debt to meet its widening budget deficits.

Of course, bond investors can always opt not to hedge, though making a bet on the direction of currencies entails an added risk. And prior to the latest selloff in Treasuries that pushed 10-year yields to the highest since 2011, data compiled by Bloomberg showed that major foreign holders actually upped their stakes by $35.4 billion in August. (Their share of the $15.3 trillion market, however, still fell to the lowest in 15 years.)

Whatever the case, some see signs of trouble. Bill Gross tweeted on Oct. 3 that foreign buyers are being “priced out” of Treasuries because of rising hedging costs, which could spur more declines.

To make matters worse, the situation could persist for years to come.

Short-term interest rates -- which determine relative hedging costs in the currency forwards market -- are far higher in the U.S. than in the euro region, and likely to stay that way until the European Central Bank catches up to the Federal Reserve. The Fed has raised rates eight times since 2015 and some forecasters expect three more by the summer of 2019, when the ECB has indicated it will finally start lifting its policy rate from zero.

Hedging Profits

That means trading desks need to pay up to get investors to swap their dollars, which earn more interest, or “carry” in trader-speak, than euros.

The trade works like this: A dollar-based investor buys euros, which currently sell for $1.1574, to invest in euro debt. To hedge against currency swings, she simultaneously enters into a forward contract to sell back the euros in three months at a fixed price, currently $1.1668 per euro. That transaction normally incurs a marginal cost. But now it produces a return of 0.81 percent, or nearly 3.3 percent annually -- the most since the euro’s inception in 1999.

(A similar pattern holds true for cross-currency basis swaps, a hedging strategy used predominantly by multinationals and central banks.)

Profits from hedging the euro have persisted for years, but they’ve gotten so large in recent months that more and more U.S. investors are taking advantage. Dimensional Fund Advisors is one of them.

The firm’s $15 billion Five-Year Global Fixed Income Portfolio, which hedges against currency fluctuations, has added $1.7 billion worth of euro-denominated government debt this year, from countries including Belgium, Finland and the Netherlands, regulatory filings through July show.

The largest holding -- five-year Austrian debt yielding 0.017 percent -- has a hedged yield of 3.31 percent. Similar-dated U.S. notes yield 3.02 percent.

Dismal Returns

“If you only look on an unhedged basis, people say, ‘Rates in Europe are extremely low, why would anyone be interested in that?” said Dave Plecha, who’s run the DFA fund since 1990.

A big reason, besides hedging profits of course, is simply the dismal returns on Treasuries. Granted, 2018 has been a tough year for bond markets worldwide, but Treasuries have been particularly hard hit as the U.S. economy strengthens. For U.S. investors, every maturity from three years to 30 years has posted losses. The 10-year note alone is down 4.5 percent as price declines deepened.

Pimco is turning to Japan. The bond behemoth’s dollar-hedged International Bond Fund held about $655 million worth of JGBs at the end of June, its biggest overseas sovereign holding, the latest regulatory filings show.

At the same time, total foreign ownership of short-term yen bills climbed to a record in June. Currently, dollar investors can get 2.84 percent a year on negative-yielding three-month yen bills, about a half-percentage point more than comparable T-bills.

Sachin Gupta, who co-manages Pimco’s $9.6 billion fund, says the interest-rate differential will eventually close. It will just take a while.

“Other countries are still lagging behind in terms of economic strength and interest rate hikes,” he said. “So this differential is likely to become more attractive over the next year or two before it goes the other way.”

--With assistance from Masaki Kondo.

To contact the reporter on this story: Katherine Greifeld in New York at kgreifeld@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Benjamin Purvis at bpurvis@bloomberg.net, Michael Tsang, Mark Tannenbaum

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.