(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The most dangerous call on Wall Street in recent years has been to predict the end of the bull market in bonds, which has lasted more than three decades. Each time U.S. Treasuries look as if they’re about to roll over and die, they quickly rebound and make even the smartest minds look foolish. Just consider the last 15 months, a period when the benchmark 10-year note yield Treasury went from about 2.45 percent to as high as 3.26 percent in October before falling back to around 2.72 percent Tuesday. Now, one influential firm says yields will fall further. Much further.

The economists and strategists at Morgan Stanley came out with a bold call Tuesday by predicting yields, which are used to help set borrowing costs for everything from corporate debt to household mortgages, will drop as low as 2.35 percent by the end of the year, a level not seen since the end of 2017. Based on the latest monthly survey by Bloomberg News, that makes the firm more bullish than any of the other 23 primary dealers, which are allowed to trade with the Federal Reserve and help the U.S. government with its debt sales. Tame inflation and lower economic growth are the main reasons Morgan Stanley reduced its year-end yield forecast from 2.45 percent, which compares with the median estimate of 3 percent in February’s monthly survey. (The next one is due out in coming days.) The point is that Morgan Stanley is unlikely to be the only firm lowering its yield forecasts with economists working overtime to reduce their economic growth estimates. The Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s GDPNow Index, which aims to track growth in real time, has fallen to a “stall speed” level of 0.3 percent, while a similar gauge from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York is under 1 percent.

Thanks to corporate tax cuts and the Trump administration’s moves to reduce regulation, the U.S. economy was able to avoid the general slowdown experienced by the rest of the world last year, but that’s changing. The median estimate of economists surveyed by Bloomberg News forecasts U.S. growth slowing from 2.9 percent last year to 2.5 percent in 2019 and 1.9 percent in 2020. Some 42 percent of business economists in the National Association for Business Economics’ semiannual survey released last week expect the U.S. to enter a recession next year. Given that, it’s a surprise anyone is betting against bonds.

BIS WARNS ON CORPORATE DEBT

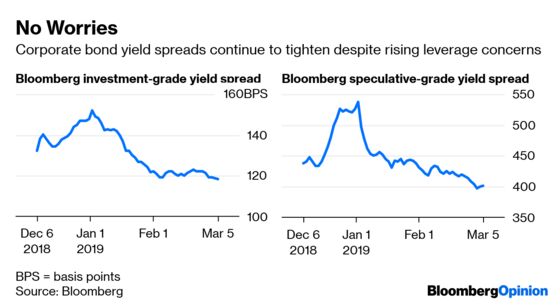

If that wasn’t enough to boost Treasuries’ appeal, then consider the growing chorus of concerns regarding the quality — or lack thereof — of corporate debt. The size of the U.S. investment-grade debt market has more than doubled since 2008 to about $5 trillion. About half is composed of bonds with ratings in the BBB tier, which is one grade above junk. “U.S. nonfinancial corporate debt as a percentage of GDP is now higher than the prior peak reached at the end of 2008,” Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas President Robert Kaplan pointed out in an essay published Tuesday. The concern is that it wouldn’t take much of a slowdown in the economy to cause much of this debt to be cut to junk, potentially creating another financial crisis. “If, on the heels of economic weakness, enough issuers were abruptly downgraded from BBB to junk status, mutual funds and, more broadly, other market participants with investment grade mandates could be forced to offload large amounts of bonds quickly,” analysts at the Bank for International Settlements — known as the central bank for central banks — wrote in a quarterly report. There are two ways to think about this. The first is that the Fed can’t raise rates much further, if at all, because of the damage it would do to bloated corporate balance sheets. The second is that companies would just divert the large sums they are now spending on stock buybacks and dividends to reducing debt if they were in jeopardy of losing their investment-grade ratings.

THE REAL THREAT FROM CORPORATE DEBT

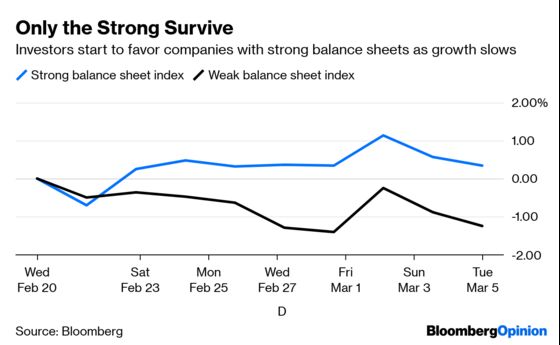

In that sense, it’s no wonder that a growing number of investors feel the real risk in rising corporate debt is not in the debt but in the equity of companies. In other words, the buyback trend that has underpinned the stock market would come to a halt. The numbers are not insignificant. JPMorgan Chase strategists estimated in January that S&P 500 companies alone would repurchase about $800 billion of shares this year and spend an additional $500 billion on dividends, in line with 2018. Plus, nonfinancial members of the S&P 500 have about $1.6 trillion in cash on their balance sheets, and cash flows from operations will reach $2 trillion this year, JPMorgan estimates showed. Perhaps this is one of the reasons the big rebound in stocks since late December has run out of steam. If a lasting economic slowdown is on the horizon, then it’s not hard to see companies switch from favoring shareholders to favoring bondholders. Although far from conclusive, it’s interesting that a basket of 50 S&P 500 companies with strong balance sheets has started to outperform a basket of 50 S&P 500 companies with weak ones, gaining 0.35 percent since Feb. 20 compared with a loss of 1.30 percent for the higher levered ones. Regardless of whether corporate debt is a real problem or not, the consensus is that it’s only going to get tougher for stocks from here. After rising about 19 percent since Christmas Eve to 2,789.65 on Tuesday, the S&P 500 is only likely to gain 3.8 percent further the rest of the year to 2,900, according to the median estimate of 25 Wall Street firms surveyed by Bloomberg News.

INDIA’S MARKETS IGNORE TRUMP

The Trump administration notified Congress on Monday that it wants to scrap trade concessions for India, the largest beneficiary of the so-called generalized system of preferences that impacts $5.7 billion worth of goods. India’s benchmark S&P BSE Sensex index of stocks responded by rallying to a three-week high. The rupee gained as well, appreciating to its strongest level since mid-January. Rather than a lack of respect for U.S. trade rhetoric, the gains are a sign of rising optimism that pending national elections will bolster the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, which is trumpeting its foreign policy prowess and military strength following a standoff with Pakistan. “A tough stance against a threat from Pakistan-based terrorists has won Prime Minister Narendra Modi praise from the Indian public, which in our view could translate into electoral gains for him and his Bharatiya Janata Party in national elections in May,” according to Abhishek Gupta, an economist with Bloomberg Intelligence. It also doesn’t hurt that the Sensex has soared 48 percent since Modi came to power in May 2014, compared with a gain of just 2.50 percent for the MSCI Emerging Markets Index. To be sure, the Trump administration’s move affects just a fraction of India’s trade flows, according to Bloomberg News’s Iain Marlow and David Tweed. Even if Modi doesn’t want to raise the temperature, “the discourse in this country has been that America needs India to balance China,” Harsh Pant, an international relations professor at King’s College London, told Bloomberg News. “And the question will be: Why is America doing this to India?"

INDUSTRIAL METALS SIGNAL OPTIMISM

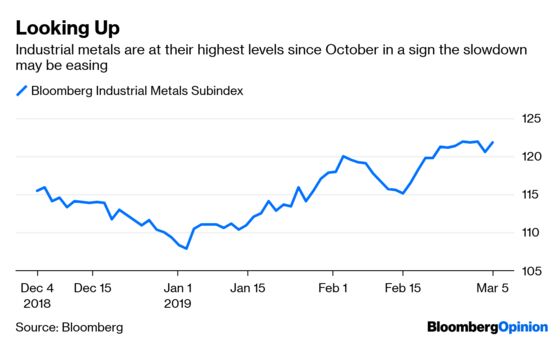

A few prominent Wall Street firms, including Goldman Sachs, have come out in recent weeks to declare that the slowdown in global growth has plateaued. That’s certainly open to debate, but the commodities market seems to agree. The Bloomberg Industrial Metals index jumped as much as 1.41 percent on Tuesday even though China, the world’s biggest consumer of such raw materials, lowered its goal for economic growth to a range of 6 percent to 6.5 percent, from last year’s target of about 6.5 percent. The new range “is definitely positive news for the market,” Jiang Hang, head of commodity investment research at GM Corporation Ltd., told Bloomberg News. “The economy is in a downturn, and if we set the target too high, there’ll be too much pressure on the government to adopt radical stimulus to support, which will have excessive aftereffects.” Copper, often trumpeted as the metal most keyed to economic growth, rose more than 1 percent. Nickel climbed to a fresh six-month high in London as rallying steel markets, falling inventories and rising electric-vehicle sales bolster the outlook for the metal, according to Bloomberg News’s Mark Burton and Caleb Mutua. Steel futures are actually up this year. The gain in metals helped push the broader Bloomberg Commodity Index up for the first time in four days.

TEA LEAVES

The story of the year so far in markets has been the dovish turn by major central banks led by the Fed. The Bank of Canada may be about to join the club. The central bank raised interest rates three times last year, with the last hike coming in October. At the time, Governor Stephen Poloz told reporters that “the reality is the economy is running at its capacity, and it is no longer needing stimulus, and so it’s our job to prevent the thing from overheating.” It’s clear now that overheating shouldn’t have been a concern. The government said on Friday that the economy grew at just 1.1 percent pace in the final quarter of 2018, the slowest rate of expansion since 2016. The Bank of Canada meets Wednesday, and no one is expecting a rate increase. In fact, market participants will be looking for clues as to whether Poloz puts aside any plans to boost rates altogether after last week’s data showed a much deeper slowdown than anyone anticipated, casting doubt on the underlying strength of the expansion, according to Bloomberg News’s Theophilos Argitis and and Erik Hertzberg.

DON’T MISS

Taleb Was Right. We’re Still Fooled by Randomness: Mark Gilbert

China Has a $1 Trillion Dirty Little Stimulus Secret: Shuli Ren

Recession Indicators Aren't What They Used to Be: Tim Duy

Moody’s Scolds NYC on Amazon, Then Gives a Pat: Brian Chappatta

Markets Aren’t Buying Denial on Climate Change: Noah Smith

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Robert Burgess is an editor for Bloomberg Opinion. He is the former global executive editor in charge of financial markets for Bloomberg News. As managing editor, he led the company’s news coverage of credit markets during the global financial crisis.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.