Biggest Oil Hedges Get Pricier on Global Aviation Collapse

Biggest Oil Hedges Get Pricier on Global Aviation Collapse

(Bloomberg) -- The cost for oil producers to lock in the price at which they sell their crude has soared because of the collapse in the aviation industry.

It emerged this week that Mexico may be trying to organize its annual oil-price hedge, the biggest sovereign program of its kind in the world. As well as Mexico, producers everywhere from Oklahoma to the North Sea will try to guarantee the future price for their barrels, often through options trades that pay out if the oil market collapses.

However, their efforts have been rendered far costlier in the past few months because airlines are not making the opposite side of the trade by insuring themselves against high prices. With international flights still way down on where they were before Covid-19 struck, the airlines have all but abandoned the options market, meaning the cost of the contracts for oil producers has spiraled.

“It’s becoming extremely difficult for big producers to hedge without the large airline flows around,” said Thibaut Remoundos, founder of Commodities Trading Corp. in London, which advises oil producers on their hedging strategies. “Some don’t have a choice and have to spend premium to buy puts, which are expensive.”

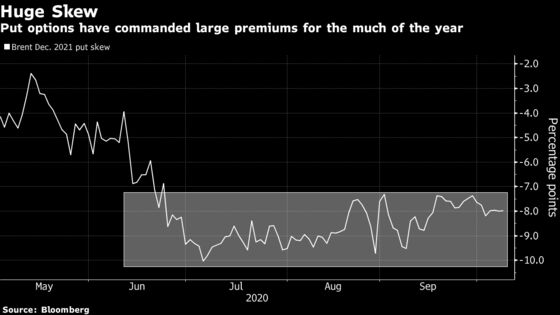

In normal times, producers like Mexico will buy bearish put options, whose volatility would normally be a fraction higher than an equivalent bullish call option. When air travel ground to a halt in the depths of the virus outbreak, that relationship -- known as the skew -- exploded. In other words, puts to insure against a price crash soared relative to comparable calls. The relationship shows no sign of returning to normal.

In the esoteric world of the oil options market, consumers, notably airlines, tend to manage their fuel bills by purchasing call options to cap what is normally their single biggest cost. They will also sell puts to cheapen that transaction. But with air travel so restrained, far fewer are selling the put options that producers want to buy, ramping up the cost of producer deals.

The premium for puts showed up clearly on Thursday. A set of contracts for 2021 that would lock in $40 a barrel for a producer traded at a cost of $4.10 a barrel. On average last year, when oil was higher and volatility was lower an equivalent option would have been between $1.25 and $1.50 cheaper, Remoundos said.

While the issue is one that affects all oil producers, the Mexican hedge -- if it’s happening as many traders suspect -- would be the starkest example. In previous years, the country paid $1 billion to lock in the value of its crude sales.

Very Thin

“The hedge market for the Mexican mix is very thin,” Mexican Finance Minister Arturo Herrera said last month.

The slump in consumer flows comes after airlines suffered billions of dollars of losses on oil derivatives that proved to be useless when the virus stopped people flying. The collapse in global air travel meant they were holding loss-making positions that covered fuel that would no longer even be used.

There’s little sign the situation will improve any time soon. In July, European airline Ryanair Holdings Plc said it won’t resume fuel hedging until the market is clear of Covid-19. The more carriers that follow suit, the fewer companies there would be to effectively make the opposite side of oil-producer hedges.

As long as put options remain expensive, it’s going to be more costly for everyone from U.S. shale producers to North Sea companies -- and producer states -- to use options to lock in their output.

“With implied volatility high versus a year ago, the cost of hedging in turn will be a little bit higher if you are only buying an option,” said Harry Tchilinguirian, head of commodities strategy at BNP Paribas. “You can lower your actual hedging cost, in the case of a producer, by selling a call.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.