Barrick Silences Its Biggest Critic by Buying Out Randgold

Barrick Silences Its Biggest Critic by Buying Out Randgold

(Bloomberg) -- For more than two decades, Mark Bristow has been a thorn in the side of Barrick Gold Corp. Now he’s its closest partner.

The 59-year-old South African will take the role of chief executive officer at Barrick after the Canadian company inked a $5.4 billion deal to buy out Randgold Resources Ltd. It’s a bigger stage for Bristow, known as an outsider for his sharp and frequent criticisms of the gold industry and a genius at running an African mine.

Bristow’s personality looms large. He’s fond of cigars and big-game hunts, as well as motocross expeditions across Africa. He’s been known to use his pilot license to fly investors directly to African mines via his private plane, and run Randgold from top to bottom, often personally handling its investor and media communications.

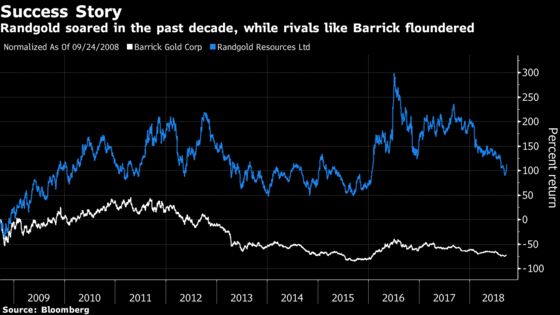

That’s the limitless energy and fresh perspective that Barrick needs, said Hunter Hillcoat, an analyst at Investec Securities Ltd. The Canadian company, led by Executive Chairman John Thornton, has lost about 70 percent of its value in the past decade.

Bristow is “a big, larger-than-life, alpha-male personality, who’s going to have to go in and see what he can do,” Hillcoat said by phone. “He’s going to be given a large amount of free rein.”

Randgold has been one of the U.K.’s great corporate success stories, delivering a 4,000 percent return since the end of 1999 -- making it the best stock in the FTSE 100 Index. It has never reported a quarterly loss and never taken a write down. In an industry dependent on the volatile price of bullion, it’s a remarkable feat that none of its rivals can match.

It’s also an achievement that Bristow trumpeted, while pouring scorn on his peers, especially those based in North America. “The industry blows it’s brains out every time. The reason we’re still in the industry is because the competition isn’t that sharp,” Bristow said in 2014.

His language softened on Monday, telling investors that the merger is not a “rescue job” for Barrick. “We have no intention to changing the way we run the company at Randgold,” Bristow said. “And if there’s anything that John and I are completely aligned on, it’s that model.”

| For more on the Barrick-Randgold deal: |

|

Despite Randgold’s stellar record, the last few years have been difficult. The company, famous for its exploration success, struggled to find new projects. It hasn’t managed to buy any new mines and faces tougher regulation in the Democratic Republic of Congo. The stock is down more than 30 percent this year.

Bristow also experienced health problems. Last year, a doctor spotted a heart murmur during a routine medical exam to renew his pilot license in Ivory Coast. Bristow first waved it away, but the doctor insisted a cardiologist follow up. Within a week, he underwent an 11-hour open-heart surgery in Johannesburg and a week of intensive care.

One of Bristow’s first challenges will be resolving Barrick’s problems in Tanzania. The company is the majority shareholder of Acacia Mining Plc, which faces a long-running dispute with the government. The Tanzanian government hit Acacia with a $190 billion tax bill, and the company has been forced to cut production.

Acacia Crisis

Last year, Bristow criticized Barrick’s handling of the crisis in Tanzania.

“One of the world’s biggest gold-mining companies invested in that country with a promise, when gold was under $300, and it hasn’t delivered in any value,” he said at the time.

Bristow’s favorite talking point has long been what he considers a lack of discipline. He repeatedly blasted executives for spending too much on mines that won’t make a profit.

Barrick has been one of the biggest culprits. It took billions of dollars in writedowns, especially around its failed Pascua-Lama project in South America, and production has fallen. Now Bristow will have to fix the problems, rather than harangue from the sidelines.

“Investors were already beginning to ask questions about the succession at Randgold,” said Charles Gibson, an analyst at Edison Investment Research in London. “They will certainly want comfort now that he will stay for long enough to apply the same approach to Barrick’s assets before hanging up his spurs.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Thomas Biesheuvel in London at tbiesheuvel@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Lynn Thomasson at lthomasson@bloomberg.net, Nicholas Larkin

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.