Barclays London Stocks Unit Is Thriving on Tax-Reduction Trades

Barclays' London Stocks Unit Is Thriving on Tax-Reduction Trades

(Bloomberg) --

Deep inside Barclays Plc, the remnants of a controversial division shuttered years ago are still making millions of dollars gaming loopholes in tax laws.

A team of Barclays traders is arranging deals that generate profit by lowering taxes on dividends, a practice known as dividend arbitrage, people familiar with the unit’s operations said. Some executives who have run the desk used to work at the London-based bank’s troubled Structured Capital Markets unit, which helped clients duck billions of dollars in taxes before it was closed in 2013.

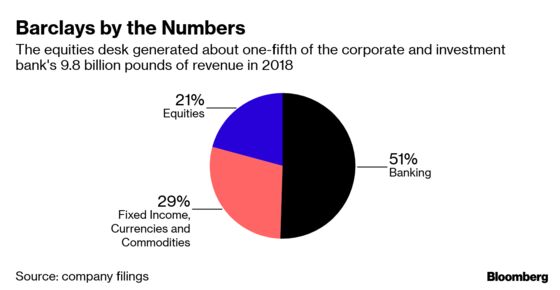

The desk that handles the deals, known internally as Delta-1 Strategic and overseen by SCM veteran Sadat Mannan, has been one of the most profitable at Barclays, according to the people, who requested anonymity as details are private. The team may be generating about 10% of the firm’s stock-trading revenue, the people said, making it an important part of Chief Executive Officer Jes Staley’s defense of the investment bank as he faces pressure from investors to boost returns.

Yet the existence of Delta-1 Strategic after the bank’s disavowal of esoteric tax trades made some executives uncomfortable, the people said. The dividend-arbitrage industry has drawn scrutiny over the past decade, and some lenders and investors are now wary of the risks the trades can pose. It’s also getting harder to turn a profit from the deals as governments close off the loopholes that enable them.

“I’m surprised that anyone could be doing anything close to a tax-avoidance product that’s similar to what Barclays was doing in its Structured Capital Markets division,’’ said Fahed Kunwar, an analyst at Redburn in London. “The compliance risk seems quite high. If I was management at Barclays, I would take a very long hard look at that business.”

Tom Hoskin, a spokesman for Barclays, said all of the bank’s trading activity “is tightly governed and complies with our tax principles.”

Tax Anomalies

Dividend-arbitrage trades target anomalies in withholding taxes that governments levy on payments made to shareholders. In a typical transaction, a stockholder lends shares before the dividend date to a party in another jurisdiction where the tax hit will be smaller. After the payout, the party hands back the stock and the firms split the tax savings. Investors can also use bespoke derivatives known as total-return swaps for the trades.

Proponents of dividend arbitrage say it’s a legal way for investors to boost their returns. The U.K.’s Financial Conduct Authority permits the activity as long as the intention is the legal “minimizing of withholding taxes,’’ according to a 2017 report.

But the practice has long attracted criticism. In 2008, U.S. senators accused banks including Citigroup Inc., Deutsche Bank AG and UBS Group AG of concocting derivatives and stock-loan deals that exploited gaps in dividend-tax laws and denied the Treasury billions of dollars over a 10-year period. Some bankers testified at the time that the trades were legal, and the firms denied wrongdoing. The Internal Revenue Service later cracked down on the business by issuing new rules.

Some U.K. firms don’t do enough due diligence around the trades, and there’s a risk they could be involved in “potentially criminal’’ activities, the FCA said in 2017, without naming any banks. Prosecutors in Germany, meanwhile, are carrying out a sweeping probe into so-called Cum-Ex trades, an aggressive form of dividend arbitrage in which multiple people claim ownership of the same shares and the right to a refund of withholding taxes. Lawmakers say the trades have cost the country 10 billion euros ($11.1 billion).

This kind of scrutiny has prompted some investment banks and investors to pull back from dividend arbitrage, according to Andrew Dyson, CEO of the International Securities Lending Association in London. Deutsche Bank is among lenders that have scaled back, people familiar with the matter said.

Delta-1 Strategic

Delta-1 Strategic sits within a broader Barclays business called equity financing, industry jargon for lending to institutional stock investors, including hedge funds and other asset managers, according to the people with knowledge of its operations. Staley has pumped resources into the division since 2017 and has cited it publicly as a source of the revenue gains posted by the bank’s equities unit last year.

One arm of equity financing is based in New York and focuses on more straightforward transactions with clients, the people said. Delta-1 Strategic’s traders in London, Luxembourg and Tokyo, meanwhile, specialize in more complex deals and have prioritized those tied to dividends and taxes.

The desk may have made more than 200 million pounds ($252 million) in Europe in 2018, much of it from trades tied to dividends, the people said. The bank’s equities unit boosted revenue by about 25% to 2 billion pounds last year, besting Wall Street rivals and helping Staley fend off critics who want him to scale back risky investment-bank operations.

Other banks, including Morgan Stanley and Bank of America Corp., also arrange dividend-arbitrage trades, according to people familiar with the industry’s workings. Yet Barclays’ equities business, one of the smallest among global lenders, has an outsize presence, one of the people said. Spokesmen for those firms, as well as those for seven other big banks, declined to comment.

Luxembourg Unit

Delta-1 Strategic has typically been busiest at this time of year, when companies across Europe make annual dividend payments. Barclays bankers have often initiated the trades, calling up stockholders and asking them to lend the bank their dividend-yielding shares, the people said.

A Barclays entity in Luxembourg, the tiny state wedged between Germany, France and Belgium, plays a key role in the trades and has housed borrowed stocks over the dividend date, according to the people. Barclays Capital Luxembourg Sarl, a subsidiary in the grand duchy that deals in equity financing, made a profit of 291 million pounds in 2017 and owned about 20 billion pounds of stock, an annual report shows.

“There’s a place for dividend arbitrage in the market, but it’s a pretty low-quality business, particularly if it’s being used simply to funnel dividends into low-tax regimes,’’ said Edward Firth, an analyst with Keefe, Bruyette & Woods in London who has a sell rating on Barclays shares. “Ultimately, it’s not driven by customers who have a business need, and it’s not driven by economic activity.’’

Delta-1 Strategic’s roots are in SCM, a division that once made about 1 billion pounds in annual revenue by helping clients, including Barclays, sidestep so much tax that U.K. lawmaker Nigel Lawson described its operations as “industrial-scale tax avoidance’’ in 2013. A series of earlier articles in the Guardian described the high-flying lifestyles of the unit’s executives and portrayed an office culture where excess and “ritual humiliation’’ were the norm. Barclays executives didn’t respond to specific allegations in the articles at the time, but they said the bank complies with taxation laws in all countries where it does business.

‘Not Appropriate’

Antony Jenkins, Staley’s predecessor, closed SCM in 2013 and introduced new tax principles for the bank. Deals where the “sole economic value is generated through tax savings’’ aren’t appropriate, Jenkins told a parliamentary hearing on banking standards that year.

The bank imposed limits on traders’ ability to finance deals with parties that have a lower dividend-withholding rate and it enhanced compliance with tax laws, according to a person familiar with the bank’s operations.

“SCM was exceptional: No other bank ever had a unit close to it in size, significance, or it seems in its willingness to pursue tax avoidance to its limits,’’ said Richard Murphy, a professor at City University in London and co-founder of the Tax Justice Network. “It was a feature of Barclays at a point in its history that no one has copied, no one wants to repeat and no one should ever want to see again.’’

Yet Jenkins didn’t shut everything. In a statement announcing the overhaul, he said Barclays would continue to do deals that involved “delivering value as part of real client transactions.’’ He retained some of SCM’s top dealmakers, including Mannan, and they continued to focus on tax-related trades, the people said. Some executives elsewhere in Barclays’ investment bank said they were uncomfortable with this as they thought it contradicted the former CEO’s public statements.

Barclays directors ousted Jenkins in 2015 and replaced him with Staley, a former JPMorgan Chase & Co. investment banker. Simon Thiel, a spokesman for the ex-CEO, declined to comment.

Cayman Islands

Mannan, 39, joined Barclays in 2001 and became a key player in SCM. He was one of a small group of bankers that structured a complex deal in 2002 for Renaissance Technologies LLC, the U.S. hedge fund founded by billionaire James Simons.

Barclays set up a subsidiary in the Cayman Islands called Palomino Ltd. Then RenTech bought a derivative giving it economic exposure to Palomino’s performance and directed Barclays to buy and sell securities on Palomino’s behalf. The arrangement enabled the bank to effectively lend more money to RenTech than U.S. rules would otherwise allow and purported to reduce the U.S. taxes due on any trading profits.

A 2014 U.S. Senate probe estimated that investors in RenTech, one of the world’s best-performing hedge funds, avoided about $6.8 billion in taxes through Palomino and a similar arrangement with Deutsche Bank. The IRS is seeking back taxes from RenTech investors who profited from the trades, including Simons and Robert Mercer, an influential backer of President Donald Trump, Bloomberg reported last month.

Barclays stopped offering versions of the Palomino trade with tax benefits in 2013 yet continued working with RenTech on Palomino, the people said. Today, the Cayman Islands entity is bigger than ever, with assets ballooning to a record 15.3 billion pounds at the end of 2017, filings show. Mannan is the longest-serving Palomino director. A spokesman for Renaissance Technologies declined to comment.

Closing Loopholes

European governments have moved to close some loopholes that enable dividend-arbitrage trades, rendering them less profitable, said Tim Smith, a managing director at Hazeltree in New York. Lending of German stocks was down 40% on May 1 compared with the same day last year, an indicator of how much activity may have fallen, he said.

Dutch pension fund PGGM NV, which oversees more than 200 billion euros of assets, engaged in dividend arbitrage tied to German and French stocks until the countries changed their rules in recent years, according to Roelof van der Struik, an investment manager at the fund. PGGM could still profit from similar transactions linked to stocks in Canada, Sweden and a few other markets but abandoned the trades in 2018 after changing its “sustainable tax policy,’’ he said in an interview.

Government crackdowns and reluctant clients may threaten future profit at Delta-1 Strategic, just as Staley comes under pressure to boost returns. The bank’s revenue for the first quarter of 2019 fell, causing investors to question whether the CEO will be able to hit his targets for the year.

“It’s become less attractive for the banks to do it,’’ van der Struik said. “And less accepted.’’

To contact the reporters on this story: Donal Griffin in London at dgriffin10@bloomberg.net;Stefania Spezzati in London at sspezzati@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Ambereen Choudhury at achoudhury@bloomberg.net, Robert Friedman, Keith Campbell

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.