Authers’ Notes on ‘Anatomy of the Bear’: TOPLive Transcript

Authers’ Notes on ‘Anatomy of the Bear’: TOPLive Transcript

(Bloomberg) -- Below is a complete transcript of entries from the live blog event “Authers’ Notes on ‘Anatomy of the Bear’” in the order they were originally posted.

03/03 10:35 ET

Welcome to Authers’ Notes, our Bloomberg book club. Today, senior markets editor John Authers will lead a conversation about Russell Napier’s “cult classic” from 2005, Anatomy of the Bear: Lessons From Wall Street’s Four Great Bottoms.

This event will start on Tuesday, March 3, at 11:30 a.m. New York time. Join us then as John discusses the book with his guests.

Andrew Dunn TOPLive Editor

03/03 11:31 ET

Professor Napier, who joins us today, is author of The Solid Ground investment report for institutional investors and co-founder of the investment research portal ERIC -- a business he now co-owns with D.C. Thomson.

Russell has worked in the investment business for 30 years and has been advising global institutional investors on asset allocation since 1995. Russell is founder and course director of The Practical History of Financial Markets course, part of the Edinburgh Business School MBA.

A director of the Mid Wynd International Investment Trust, he is a member of the Investment advisory committees of Cerno Capital and Kennox Asset Management.

Andrew Dunn TOPLive Editor

03/03 11:32 ET

In 2014, Russell founded the charitable venture The Library of Mistakes a business and financial history library in Edinburgh that now has branches in India and Switzerland.

Russell has degrees in law from Queen’s University Belfast and Magdalene College Cambridge. He is a Fellow of the CFA Society of the U.K. and is an honorary professor at both Heriot-Watt University and the University of Stirling. When not engaged in the activities above Russell reads too much financial history, is a keen fly fisherman and grows his own organic vegetables.

Andrew Dunn TOPLive Editor

03/03 11:33 ET

Napier’s Anatomy of the Bear, for those who have not had the chance to read it during the excitement of the last few weeks, is a cult classic work of investment history. He spent two years in the archives to see exactly what people were talking about, and what news they were reading, in the weeks around the bottom of the four great bear markets of the 20th century -- in 1921, 1932, 1949 and 1982.

His conclusions were that deflationary pressure helps to force bear markets, in combination with overvaluation of stocks. The bottom comes not in catharsis and revulsion, but rather when all hope has been lost and apathy reigns.

John Authers Senior Editor

03/03 11:33 ET

The first edition of Anatomy of the Bear accurately told readers not to trust the rally that followed the bursting of the dot com bubble, and warned that another sell-off lay ahead. That was proved right. Subsequent editions said that March 2009 was not a bear market bottom to match the four covered in the market, and many now argue that he has been proved wrong on this.

I saw the book on the desks of many a fund manager during the years before and after the crisis. With markets now in their scariest state since 2008-09, it is a great time to return to it.

John Authers Senior Editor

03/03 11:35 ET

Greetings, Russell. The first question we were planning to ask was a simple one, from Cross-Asset reporter Sara Ponczek:

Where do we stand now? Is there a period that’s most comparable to our current situation?

After the events of the last few hours, I suppose by that we now mean: Is there a period remotely comparable to one where the Federal Reserve has made an emergency cut of 50bps, bringing 10-year Treasury yields to an all-time low, barely two weeks after the S&P 500 hit an all-time high?

Let’s start by trying to locate exactly where we are, and what long-term effect the Fed’s action might have.

John Authers Senior Editor

03/03 11:35 ET

There is one dramatic period that looks like this -- October 1929. Clearly, the decline in the stock market on that famous day was much bigger than what we have seen in the past 10 days, but the Fed cut the day of the big deadline.

Despite that very large decline in the equity bear market, they were still at very high PE ratios when that cut came.

Russell Napier Author, Anatomy of the Bear

03/03 11:38 ET

That raises one big question: The Fed has been greatly criticized for its policies between 1929 and 1932, and it started with rates considerably higher.

What should the Fed do now to avoid a similar outcome? (For asset prices, or for the economy).

John Authers Senior Editor

03/03 11:44 ET

The book suggests that it is deflation that destroys equity valuations as it pushes cash flows and asset prices lower and, thus the risk of equity eradication rises.

Bernanke famously gave a concise speech on November 2002 on what the Fed could and should do. They have not been through all that playbook yet, but essentially they need to boost the growth in broad money -- and this is something that have failed to do with their extraordinary monetary policy.

Things are much worse elsewhere, especially in Europe, where they have got to the situation that Bernanke warned a central bank should never get to: zero interest rates and falling inflation or deflation.

I would recommend freeing up banks to buy a lot more securities and thus create money this way. However, outside the U.S. they will probably be more tempted by helicopter money.

Russell Napier Author, Anatomy of the Bear

03/03 11:46 ET

It’s still only a couple of weeks since the S&P 500 hit a new high, and that leads to this question from old friend Dec Mullarkey of SLC Management in Boston:

“Lofty valuations alone have generally been a poor market timing indicator. It seems you also need investor euphoria to really drive a bull market.

“During the last twelve S&P 500 bull markets, returns leading up to the peak were, on average, 58% over the prior two years and 25% over the prior year. Suggesting bull markets end with a bang and not a whimper.

“Do most investors get captured by momentum that in turn fuels the overshoot and downturn? Or is this some aggressive price discovery where investors keep pushing until they eventually find the break point?”

Or, put briefly, was the buying we saw in February the final melt-up to a bear market top?

John Authers Senior Editor

03/03 11:48 ET

There are two ways valuations can fall -- driven by inflation and higher interest rates or driven by deflation.

The book points out that some of our bear markets last a very long time indeed, such as 1901-1921 and 1968-1982. These market valuations declined primarily because inflation and interest rates went higher and it was difficult to stop that, even over many cycles.

However, all ended with the risk of deflation as the central bankers got over-aggressive against inflation. The key outlier was 1929, when we went straight to deflation without first going through a long bear market associated with the battle against inflation.

Today, it is very clearly a deflationary shock we face, so valuations can fall very quickly. This happened in 1921, 1932, 1949 and even in 1982 given the U.S. banks were in crisis.

Deflation brings valuations down, full stop, but to stress: Things are much much worse in Europe where valuations are a lot lower.

Russell Napier Author, Anatomy of the Bear

03/03 11:51 ET

Following on the theme of cognitive dissonance, as bond yields hit record lows just after stocks hit record highs, we have this question from Tamas Vojnits, former chief economist of OTP Bank in Budapest:

“I don’t think, and indeed portfolio theory suggests, that one can evaluate asset class valuations separately, reduced to only one asset class.

“For a long time now, rising equity values have been supported by declining and very low long term yields (negative real yields).

“Is it possible that we have two equilibriums, one described by ultra low risk free rates coupled with high equity valuations and another with ‘normal’ interest rates coupled with much lower equity market valuations?

“Fundamentals aside, is it possible that we cannot get from one (the first) equilibrium to the other (the latter) without a major equity market disruption and therefore we are stuck at a sub-optimal equilibrium?”

John Authers Senior Editor

03/03 11:54 ET

Can we reconcile record low interest rates with economic growth but more importantly stable household and corporate cash flows and asset prices?

Clearly, this is something the equity market has reconciled itself to and with some justification based on the past 10 years of lower long-term bond yields but decent growth and corporate earnings.

However, it is highly unlikely that the two can ultimately be reconciled, even in an age when the long-term bond yield is depressed by central bank actions. The book covers how technological innovation often creates the illusion that the “new economy” can be a combination of high growth and record low interest rates. It has never lasted, and all the major high valuations coincided with such a belief.

As discussed, the money and credit analysis this time suggests that the dissonance is believing that bond yields go ever lower but growth does not. So for me it’s a deflation shock with valuations falling quickly. However, history shows the dissonance can be that the technology is not as deflationary as the market thinks, and inflation -- often assisted by monetary policy -- erupts.

In that case valuations for equities fall much more slowly.

Russell Napier Author, Anatomy of the Bear

03/03 11:54 ET

I’m sure everyone is aware by now, but just to reiterate, the Federal Reserve just cut rates by 50bps this morning in an emergency move.

It was the first of the sort since 2008. Ten-year Treasury yields are now trading at 1.03% with the two-year yielding 74bps.

Pretty amazing.

Sarah Ponczek Cross Asset Reporter

03/03 11:55 ET

Even if this is a “bear market rally,” can’t investors enjoy and profit off of it?

What’s the best way to go about that, while still being prepared for pressure that will push equities to “levels associated with the bear market bottoms of 1921, 1932, 1949 and 1982,” as you see it?

Sarah Ponczek Cross Asset Reporter

03/03 12:01 ET

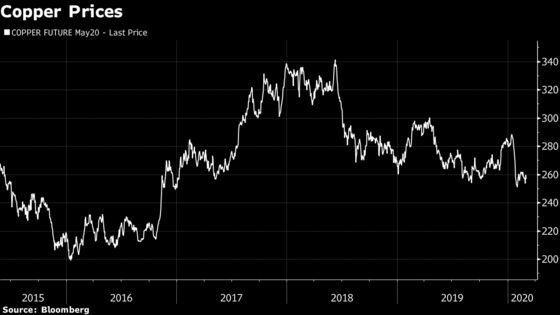

I was lucky enough to call the bottom of the equity market in 1Q 2009, even though I still do not think that was a great bear market bottom -- valuations were too high. What I looked at on that occasion was: commodity prices, TIPS-indicated inflation, the copper price and corporate bond spreads. If the Fed is successfully staving off deflation, we would expect that to be reflected in these indicators. They were lead indicators at our great bottoms and also in 2009.

So that might be the basis for trading equities but to stress: The key deflationary forces in the world are far from U.S. Shores, and the ability of the Fed to pivot the world on one interest rate move has to be in doubt.

I noted that after the emergency rate cut, copper is still down. Watch those indicators, but fundamentally equity valuations are high and this prospect is for deflation -- a dangerous time to trade equities for a bull market rally.

Russell Napier Author, Anatomy of the Bear

03/03 12:02 ET

(Incidentally Sarah, “pretty amazing” is how Lady Diana responded when asked what her first impressions of Prince Charles were, at the press conference where they announced their engagement.

So much going on this morning and I suddenly get an echo of a news event from my British youth....)

John Authers Senior Editor

03/03 12:02 ET

Russell mentioned that copper is still down today, even after that emergency rate cut. And not only is that true, copper prices have been falling precipitously ever since mid-2018. See for yourself:

Sarah Ponczek Cross Asset Reporter

03/03 12:03 ET

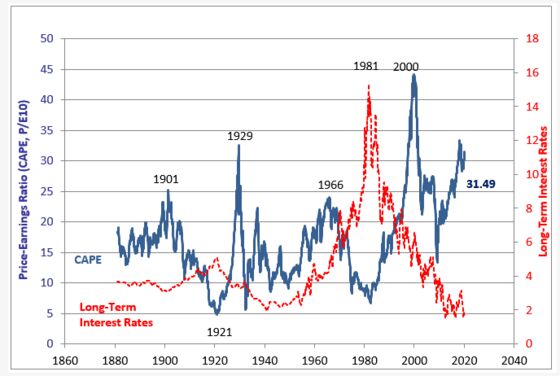

Let’s move to the question of valuation. Reader Gordon Graham raises an issue that has been very controversial in recent years:

“What does Russell think of the cyclically adjusted price earnings multiple (CAPE)?”

For context, Yale University’s Robert Shiller famously used the CAPE in 1999 to predict the bursting of the dot-com bubble, while Russell’s first edition of Anatomy used CAPE valuations to show that another big fall in share prices lay ahead.

In the years since, CAPE has continued to show that the market is too expensive, yet the S&P 500 keeps rising. Is there something wrong with the indicator (which compares prices to a 10-year average of real earnings), or with Tobin’s q, which compares prices to the replacement value of a company’s assets?

Graham handily provides this link to a page on Andrew Smithers’s website, which shows the latest measures of CAPE and q.

John Authers Senior Editor

03/03 12:07 ET

There is nothing wrong with CAPE and q as indicators of value, but we have lived in really exceptional times.

The exceptional times are a period when economic growth has been strong, corporate profits as a percentage of GDP have risen and, despite decent growth, inflation has been low.

Indeed, inflation has been so low that we have had two major deflationary shocks in the past 20 years -- when the S&P fell by 47% in 2000-2003 and 57% in 2007-2009. In deflation, valuations came down close to averages, but exceptional monetary policy reversed the deflation and valuations rebounded.

Crucially, there has been no period since 1995 when inflation stayed above 4.0% on any consistent basis. This is a new normal in a fiat currency system and, in my opinion, is the reason many think the CAPE and q have ceased to mean-revert.

Deflation which central banks fail to reverse for some time or inflation rising through 4% would be the two key triggers to send us into a “normal” mean reversion for CAPE and q. To stress yet again: Those key deflationary forces may be coming from far from the U.S. and the Fed’s ability to fight them is weakening.

Russell Napier Author, Anatomy of the Bear

03/03 12:08 ET

For reference, this is the latest graph of CAPE, as it appears on Shiller’s website. Note that long-term interest rates have almost halved since he did this chart!

Also note that the CAPE on its face remains very bearish -- higher than the top before the collapse of 2007-08, higher than the top in 1966, and not all that far off the top in 1929. Could it yet be proved a good indicator?

John Authers Senior Editor

03/03 12:10 ET

On the question of deflation somehow coming as a surprise to investors despite ever-lower bond yields (the 10-year is at 1.0377% as I type), is there a possibility that the true financial effect of coronavirus will be to give people a reason, or an excuse, to accept that we have a deflationary environment?

And as your first bear market bottom in the book comes in 1921, after three years that had been dominated by the fight against Spanish flu, are you aware of any evidence of whether that epidemic had any clear impact on markets?

John Authers Senior Editor

03/03 12:15 ET

Indeed I believe that the solution to inflation is higher broad money growth and, over 10 years of trying, global central banks have failed to push this higher.

I have just written a long piece for clients focusing on where the way of creating money will be entirely re-evaulated, and there will be a move to helicopter money.

However, that does not come quickly and if commercial bank balance sheets are now unable to expand, then broad money growth will stall or even contract again. A failure to create money will be even more obvious.

Covid-19 can play a role in that failure. I did not see much reference in the 1921 Wall Street Journal to the deflationary impacty of the Spanish flu. It must have played a role, but the key cause was record high post-WWI commodity prices, which collapsed, bringing the largest ever annual deflation to the U.S. Fed policy was restrained by the gold standard.

Crucially, as Jim Grant points out in his book on this recession, bank balance sheets stayed rock solid. The issue today is that global debt-to-GDP is at new all time highs.

So can the credit system remain robust? If not, then deflation can get out of control and Covid-19 will be the trigger but not the cause. It’s the high debt-to-GDP ratios and bank fragility, particularly outside the U.S., that is where the damage is done by Covid-19.

Russell Napier Author, Anatomy of the Bear

03/03 12:17 ET

A follow-up on CAPE: With that said though, do you buy the argument that valuations may be structurally higher in the face of lower rates?

This story that my colleague published late last year notes that since 1990, the CAPE ratio has averaged 26 -- 85% higher than the mean level over the first 90 years of the 20th century.

Or are those who are pointing to structurally higher valuations dooming themselves by ignoring history that should eventually repeat itself?

Sarah Ponczek Cross Asset Reporter

03/03 12:17 ET

That’s covered by the answer on whether inflation can be kept above zero and below 4%. If so, then we could refer to a new structurally high valuation for equities.

I have given my reasons why that will not be sustainable, and I have been of the view for some years that it will be a deflation shock, associated with lower corporate cash flows and asset prices, that will be the key cause to bring equity valuations lower.

Many would see the last decade as a new stability of low inflation and decent growth. I see it as a Minsky period, when fake stability crated massive risk-taking, which shows up as ever higher debt-to-GDP levels. These high valuations are a product of a fake stability that has sown the seeds of its own destruction.

This is the way cycles work -- or at least how Hyman Minsky thinks they work. Clearly, equity investors today disagree.

Russell Napier Author, Anatomy of the Bear

03/03 12:18 ET

Speaking of helicopter money, Hong Kong recently made this announcement:

Hong Kong to Give $1,284 Cash Handouts as Recession Bites

Sarah Ponczek Cross Asset Reporter

03/03 12:24 ET

Following on from Russell’s point on Minsky, I totally, utterly agree.

You can find the transcript of our last book club chat, when we discussed Minsky’s ideas, here.

John Authers Senior Editor

03/03 12:24 ET

As we’ve raised the issue of forces beyond the U.S., here’s an interesting question on China from our regular contributor Jun Gao:

“Do we need to supplement some information on China’s stock markets which are unique in many ways? Bloomberg’s Shuli Ren wrote about that here.

“Since the Chinese government doesn’t need to worry about criticism if it bails out the market, there might just be a ‘national team’ standing by to pour billions of dollars into market.

“Could such a reaction possibly help? Or might it create traps for others?”

And I suppose we should add: Can the analysis in the book help us when dealing with a market still as closed and manipulated as mainland China’s?

John Authers Senior Editor

03/03 12:27 ET

Agree on that.

I still wonder why anyone would want to commit their savings to a command economy though?

I do think the virus does give an excuse for the People’s Republic of China to move to just those policies, but they will likely be very bad news for the exchange rate. That is the key deflationary force that might enter the history books that other central bankers could not fight. It would take governments to do that.

This is exactly where we are, and governments will get more involved. Investors who benefited from quiet government and low central bankers -- since 2009 -- have to be prepared for government action, and if it has something of the command economy about it, then why is this good for equity investors.

So it may not just be China that uses command economy responses. Europe might have to move quickly in a similar direction. These massive structural changes in economies, which would be accompanied by financial repression, would send capital flooding to the U.S., where a world of market prices is more likely to be maintained longer, though nobody could call it a pure market economy.

Personally, I do not invest in command economies -- and in the long run, how do you run one without capital controls?

Russell Napier Author, Anatomy of the Bear

03/03 12:29 ET

One further question about the international differences: If we look at any non-American developed markets, they appear to have been in a secular bear market since the beginning of 2000. The following chart does not include reinvested dividends, but it is also in nominal terms, not making any allowance for inflation:

Are there any parallels for one of the major stock markets going on an epic tear while all the others languish in a bear market? And what are the implications?

John Authers Senior Editor

03/03 12:32 ET

The MSCI World ex-U.S. Index is now below its 2011 and 2007 level. It is just 7% above its 2000 level. Even with dividends reinvested, the total return for non U.S. equities since 2000 is just 75%, and over that period, U.S. inflation has been 47%. So, dire returns.

There is, of course, a parallel as other equity markets did not have the great boom that the U.S. had in the second half of the 1920s. Indeed, many were suffering from economic difficulties as they struggled to rebuild the gold standard post-WWI.

Arguably, their difficulty in growing played a role in keeping global inflation low. The U.S. equity bull market also sucked in capital from across the world and, under the gold standard, this led to the creation of more liquidity in the U.S.

We have a different monetary system today but a lot of the downward pressure on inflation in the U.S. has once again come from beyond U.S. shores. Those struggling with lower prices have found it difficult while the U.S. has benefited from this imported deflation. So, the best example of this major divergence may be the 1920s, though of course there were many differences, particularly in relation to the monetary standard of the day.

Russell Napier Author, Anatomy of the Bear

03/03 12:36 ET

Where does the advent of passive investing and ETFs fit into market structure and history (if at all, in your opinion)? And how would this affect historical comparisons?

Sarah Ponczek Cross Asset Reporter

03/03 12:38 ET

There is nothing quite like this, though some draw comparisons with the portfolio insurance automated system that contributed to the 1987 crash.

Investing new funds on the basis of existing market capitalization is not capitalism. I don’t know what it is, and I suspect if Adam Smith was sitting here neither would he.

To describe the problems with it would take a book, but it clearly plays a major role in distorting capital allocation and, over the long run, that is not good news for corporate returns or society.

As to when the damage done by such flows is apparent in the real economy, it might already be happening with the rise of key oligopolies. Society is unlikely to be able to live with this concentration of power that comes to those corporations that see their cost of capital constantly lowered by an algo.

In terms of financial market impacts, it should make it easier for active managers to outperform when the machines become too big as market players. Of course, none of us knows when that might happen, but watching equity value indices for any sign of life relative to momentum may provide some indication of when it arrives.

As everyone reading this knows, it’s been a long time in the wilderness for value investors, so the machines are still in control. Teddy Roosevelt would have turned them off by now given the consequences!

Russell Napier Author, Anatomy of the Bear

03/03 12:42 ET

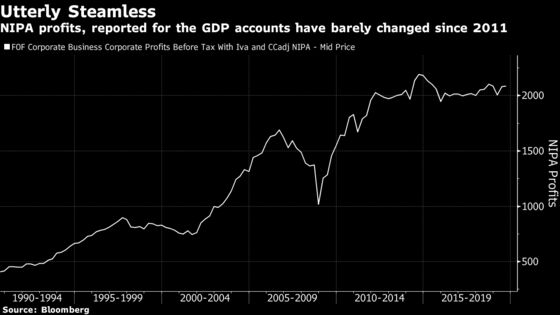

Your work outlines how corporate profits can continue to decline long past a bear market bottom.

Are investors often too fixated on the growth trajectory of company earnings?

Sarah Ponczek Cross Asset Reporter

03/03 12:45 ET

The great bear markets are really about falling valuations and often they occur as corporate earnings are growing. This is obviously much more true in those periods when we had long declines in valuations such as 1901-2921 and 1968-1982.

I’d argue that, for MSCI ex U.S. Index, this has been underway for some time, with earnings coming through OK but with the price of equities in general making no headway since 2001 and actually since 2000.

Interestingly, the previous long bear markets saw valuations fall primarily because interest rates were rising and thus a higher discount rate played a role in bringing down valuations even as corporate earnings rose.

This has clearly not been the case for this long bear market in non-U.S. equities. This is particularly worrying as it suggests that investors see the very low interest rates in, say, the eurozone and Japan as being worrying signs for future growth, rather than positive signs by which we should use a low discount rate and combine it with a high growth rate.

This is correct in my opinion, and the creation of the euro in particular has screwed up how we might look at a low discount rate. It can be a sign of a structural failure to create a single currency and not the positive low discount rate in normal cyclical times.

Covid-19 will further strain the relationship in Europe as now 19 governments will have to agree on what to do given that the ECB alone has played out. Equity investors are pricing in failure to create a functional single currency. I think they are correct.

Russell Napier Author, Anatomy of the Bear

03/03 12:46 ET

Returning to Sarah’s question on earnings, the earnings as reported by the S&P 500 companies have unmistakably flattened out:

Meanwhile, the NIPA corporate profits compiled as part of building the GDP calculations, without the aid of accrual accounting, have been stagnant for the best part of a decade:

Are these numbers as terrifying as they appear? Are they historically an indicator of an oncoming bear?

John Authers Senior Editor

03/03 12:48 ET

By the way, on the rise of oligopolies as an unintended consequence of the rise of passive investing, you might want to look up the transcript of our December book club chat, which was about competition policy (or the total lack of it).

You can find it here.

John Authers Senior Editor

03/03 12:52 ET

Earnings: This is something that we focus on in “The Practical History of Financial Markets” course in run in London.

The period in the chart worth looking at is the late 1990s. You will see NIPA profits coming off sharply at a time when S&P EPS continued to rise sharply. It turned out that NIPA profits were a more accurate guide, but of course any investors who followed that advice missed the late-90s bull market.

So, it’s a dissociation between NIPA profits and S&P 500 EPS that can go on for a long time and investors have not been rewarded, sometimes for many years, for taking their lead from NIPA.

Of course, the 2000-2003 correction in equity prices was 47%, so perhaps whoever laughs last laughs loudest -- if they are still employed. Fundamentally, U.S. corporate profits-to-GDP have simply not mean-reverted they way they have done throughout history, or at least the history we have data for (from 1929). They will do so and labor, the creditor, the tax man and even the defined-benefit pensioner will ultimately get their higher share.

The NIPA data may suggest that we are already seeing something of that mean-reversion given that GDP has grown as it had flat-lined. As we discovered in both deflationary shocks of the past 20 years, accountancy legerdemain was behind much of the inflation of S&P 500 earnings.

Russell Napier Author, Anatomy of the Bear

03/03 12:54 ET

It’s a fascinating discussion. Thank you all. I’d like to ask where does gold fit in the current environment?

Gold does well in an inflationary and weak-dollar environment. But it has been on a run in the current environment of disinflation and a relatively stable/strong dollar. Granted, low real rates reduce the opportunity costs for holding gold. But as Warren Buffet says, gold has no “utility”:

“God gets dug out of the ground. Then we melt it down, dig another hole, bury it again, and pay people to stand around guarding it.”

Is the gold rally a vote of no confidence in central banks’ fiat money? or something else?

Ye Xie Markets Reporter, New York

03/03 12:55 ET

Hold gold in your hand and then explain the emotion. If markets are emotional and based on “guesstimates” of future returns, holding a very dense metal that never tarnishes may make you “feel” different.

Particularly as there are always people who will buy it from you.

Pimm Fox Markets Live, New York

03/03 12:58 ET

Gold has that impact on some people but not everyone! It is what makes it so interesting, and as you know J.M. Keynes had rather a different view on gold.

Gold has not floated relative to money for very long given its long fixing to key exchange rates. However, when it has floated it has benefited from falling real rates of interest and had a problem with rising real rates of interest.

With a deflation shock now likely imminent, this would send real rates higher and in a frightening way, given that many interest rates are at the lower bound. However, if the answer to this shock is helicopter money, gold enters a bull market that will last for decades.

This is where we are headed, and helicopter money must come with financial repression -- something I have written a 60-page tome on for clients. I cannot go through all those arguments, but gold is the stand-out asset class in a financial repression. So in the world of finance Covid-19 will be remembered not for the damage it did, but for the new form of cure it unleashed -- particularly in Europe but also probably in Japan.

Gold benefits from this shift for a very long time indeed.

Russell Napier Author, Anatomy of the Bear

03/03 12:59 ET

One final question. I can’t help but ask: If you had one piece of advice for investors, what would it be?

Sarah Ponczek Cross Asset Reporter

03/03 13:02 ET

Avoid investing in anything in Europe! The new response there cannot be solely monetary and must involve major government actions.

While all the talk is of fiscal expansion, I think it comes as helicopter money, as Christine Lagarde has been pushing for this since her confirmation before the European parliament.

When Japan did this in December ‘31, the yen fell 44% against the GBP and 60% against the USD. While such outsize moves may be very unlikely, anyone with savings in Europe will know that “euthanasia of the rentier“ is the key goal of policy makers and they will rush for the exits.

Ultimately, of course, those exits will be closed. Capital controls are on their way back, and even the head of the IMF has taken to publicly writing about what a good thing they are. That’s a change that means we are definitely “not in Kansas anymore.”

Russell Napier Author, Anatomy of the Bear

03/03 13:08 ET

For a discussion of helicopter money, take a look at our chat from October, when we spoke with Frances Coppola about her book, The Case for People’s Quantitative Easing. You can find the blog here.

Andrew Dunn TOPLive Editor

03/03 13:09 ET

I think that must mark an end to what was by quite a margin the most eventful book club chat we have yet had. While we were typing, the 10-year yield dipped as low as 1.0199%, but it is now almost back up to the dizzy heights of 1.04%. Not one to forget for a while.

We cannot thank Russell enough for sharing his wisdom on such a hectic day, and giving us all an opportunity to get some perspective, even if it was perhaps (to paraphrase Spinal Tap) too much perspective.

Now, for the next book club selection, I think we are all in need of learning something about public health at present. And we could also do with some grounds for optimism. So let’s read the instant classic Factfulness by Hans Rosling, which brilliantly details how much the world is getting better, and how many inroads have been made against endemic disease and against poverty.

It is brilliant, briefly written, and it opens up a whole new perspective with reasons for optimism.

We will convene to discuss once more some time next month. And with luck we will choose a day when the markets are a little calmer. Thank you to all for taking part.

John Authers Senior Editor

To contact the reporters on this story: John Authers in New York at jauthers@bloomberg.net;Sarah Ponczek in New York at sponczek2@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Andrew Dunn at adunn8@bloomberg.net;Tal Barak Harif at tbarak@bloomberg.net

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.