At Hedge Fund That Owns Trump Secrets, Clashes and Odd Math

The threat was blunt: Back off, or there will be trouble.

(Bloomberg) -- The threat was blunt: Back off, or there will be trouble.

The 2016 presidential campaign had just ended, and Michael Cohen was fresh off handling hush money for Donald Trump. Now he was working on behalf of Chatham Asset Management, a $4.3 billion hedge fund that owns the National Enquirer.

Chatham and the Enquirer’s publisher, David Pecker, had turned to Trump’s fixer as a mediator. They wanted to kill a lawsuit by the former head of another Chatham company. Before long, the Chatham camp would make good on its threat against that executive, unleashing a tale of sex and money worthy of the Enquirer.

Playing tough is the Chatham way. The firm and its founder, Anthony Melchiorre, have a reputation for hard-edged business.

“They are scrappy, and they aren’t afraid of litigation to defend their investments,” said Leon Cooperman, a recently retired hedge fund mogul who is a Chatham investor and part owner of American Media, the Enquirer’s publisher. “They make money for their clients.”

Yet, over the years questions have swirled around Chatham. Traders have privately criticized what they see as lofty valuations of illiquid securities. At least one executive –- the one Cohen and Pecker sparred with -- has accused the New Jersey firm of market manipulation. Federal regulators have been asking questions, too.

Chatham hasn’t been accused of wrongdoing by authorities, and the fund had no comment on its interactions with federal inspectors. A spokeswoman for Cohen declined to comment, and a spokesman for American Media and Pecker didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Cohen’s assignment: Get Carl Grimstad, the recently fired CEO of payments processor iPayment Holdings, to the table. There, they tried to prevent him from pursuing a lawsuit accusing Chatham-backed iPayment and its board member Pecker of ousting him unfairly.

Cohen’s involvement was detailed by people with knowledge of the talks. “Chatham has never had any relationship with, spoken to or compensated Michael Cohen,” a representative for the firm said in response to queries from Bloomberg. “Any statement or implication otherwise is false.” Chatham hasn’t denied Cohen’s participation in the meeting.

Sue, Chatham lawyers warned, and we’ll drag your family into this, according to court testimony.

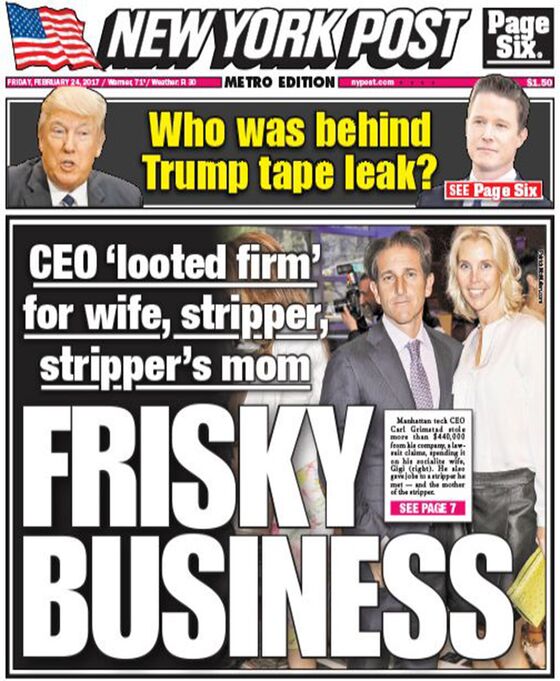

That’s exactly what happened. After Grimstad filed his suit, the Chatham camp countered, claiming Grimstad had used company money to pay a Las Vegas escort $4,000 for “sexual activities” and later hired her and her mother. The New York Post put the story on its front page under the headline “Frisky Business.” (Grimstad has called those allegations “false and meritless.”)

It’s no wonder Chatham’s side would enlist Cohen, long known for his doggedness on behalf of Trump. And as it happened, the hedge fund owned the tabloid, the National Enquirer, that he had just used to try and catch and kill stories about the future president.

SEC Questions

Behind the salacious headlines was an issue that’s drawing scrutiny from regulators: bond prices. Grimstad claimed in filings that Chatham had manipulated iPayment bonds to seize control of the company.

The Securities and Exchange Commission has stepped up examinations of various bond funds lately, inquiring about their relationships with brokers and how they value debt. Wall Street’s main regulator has been looking into opaque markets since the financial crisis, uncovering a wide swath of bad behavior from lying salespeople to bogus quotes from brokers.

Chatham itself has been undergoing its first ever exam by the SEC’s inspections division, according to people familiar with the 16-year-old firm. SEC employees have questioned the firm on subjects including its pricing of bonds and conversations with various bond dealers. An SEC spokesman declined to comment.

The SEC has increased its focus on the valuation of securities across the market, said Jacob Frenkel, a lawyer at Dickinson Wright. Recent cases brought by the regulator show it’s “trying to ensure that investors have a full and fair understanding of how instruments in the market are being priced.”

Chatham’s trading has drawn scrutiny before. In 2016, the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority opened a review of the brokerage Seaport Global Securities that, while focusing on that firm, included an examination of its relationship with Chatham, people familiar with the matter said. The next year, Seaport received internal complaints that brokers there agreed to buy bonds from Chatham with the promise the hedge fund would repurchase them at higher prices, according to people with knowledge of the situation.

Finra, the brokerage industry’s main watchdog, subsequently concluded its review, and it’s unclear what if anything resulted from it. The regulator declined to comment.

Seaport Global defended its practices. “Since it was founded in 2001, Seaport Global has been in full compliance with all laws and regulations governing our industry,’’ the company said in a statement. It declined to comment further.

‘Street Fighter’

This much is sure: Chatham founder Melchiorre, 51, has a formidable reputation. A Chicago-area kid who studied economics at Northwestern and got an MBA from the University of Chicago, his high-toned education didn’t reduce the intensity of the former high-school football star.

After stints at Donaldson, Lufkin & Jenrette and Goldman Sachs Group Inc., Melchiorre landed at Morgan Stanley in 1998 where he rose to head the junk-bond trading group. He built his stature as a temperamental money-maker at the white-shoe firm.

His behavior infuriated some senior executives, according to former colleagues. Although not physically imposing, Melchiorre could be foul-mouthed and loud, and would berate fellow traders as he bopped around the trading floor in his stocking feet.

“He’s a street fighter,” said Mike Rankowitz, his boss at Morgan Stanley. “There are people who don’t like him. That’s because they are losing to him.”

After he departed amid a round of layoffs, Melchiorre quit Manhattan to join the “Jersey Boys,’’ a clique of hedge funders across the Hudson River that included billionaires Cooperman and David Tepper.

It was a lucrative move. Named after the leafy suburb where it’s based, Chatham has posted average annual returns of about 10 percent, trouncing many of its competitors. That kind of showing helped the firm attract $300 million from investors this quarter, a person familiar with the matter said. Long-term clients include the state pension fund of Chatham’s home state, New Jersey.

Yet its recent focus on tough-to-trade investments has given some clients pause, and initially drove off investors such as the Ohio state pension fund.

Price Mystery

The iPayment case thrust questions about Chatham’s bond-trading methods into the open. Grimstad claimed Chatham artificially drove down the price of the bonds by almost 30 percent in a single trade, effectively blocking a debt-restructuring effort so it could capture control of the company. Within weeks, the notes were back at about par.

Price swings on the trades described in the lawsuit marked the biggest-ever percentage changes in those securities, data reviewed by Bloomberg show.

Chatham said at the time that the allegations were baseless and without merit.

The firm’s assets have doubled in the past three years. Over that time, Chatham has sunk even more money into one of its most controversial investments: National Enquirer parent American Media, which accounts for about 16 percent, or $400 million, of the $2.5 billion that Chatham manages in its main fund and related accounts.

Two other old-line media investments, Postmedia Network Canada Corp. and McClatchy Co., have become central to Chatham and its thesis that it’ll make money in an industry others are fleeing.

In all three cases, Chatham bought most of the subordinated bonds, plus stock. Those investments amounted to a bet that the companies would acquire competitors and cut costs. Chatham has been restructuring their debt to give them more time.

Their bonds, though, haven’t suffered. And given the strains in the print-media business, the strong price of the debt is difficult to explain, traders say. Postmedia, where Pecker sat on the board until last August, has posted annual losses for most of the past decade. Its bonds rarely change hands.

Yet its junior bonds offer yields comparable to more senior securities. The notes don’t pay regular interest in cash, a sign of their inherent riskiness. At least five other traders who’ve looked at the bonds say their prices seem too good to be true.

A similar story has unfolded at newspaper publisher McClatchy, which has posted annual losses since 2015. Its bonds staged an improbable rally last year, charting a steady climb over 50 percent from 80 to 125 cents on the dollar. That made it one of the best performing bonds in the world at the time. It even offered lower yields than some blue-chip companies.

“That’s just not how bond math works,” said Michael Terwilliger, a portfolio manager at Resource Credit Income Fund. “I wouldn’t even begin to consider owning it at that level. Something other than fundamentals are playing a huge factor in those bonds.”

In response to questions about the prices, Melchiorre sent a statement through a representative: “We have tremendous conviction in our fundamental thesis on late stage media consolidation in North America and competitors are free to express opposing views.”

With McClatchy, the hedge fund also designed a trade aimed at reaping a windfall through credit-default swaps. Such wagers have come under increased scrutiny from regulators in the last year.

Trump Secrets

Then there’s American Media. Chatham took on more American Media debt in recent months, getting Seaport to arrange a deal after Credit Suisse Group AG got cold feet amid public furor over the publisher’s antics in the 2016 presidential election. American Media now owes debtholders in excess of $1 billion, more than the book value of its assets. Despite the company’s financial distress, its bonds traded near par until December, and after dropping, have been climbing back.

Those zero-coupon bonds maturing in 2024 offered lower yields than five-year U.S. government bonds over several months last year.

For the low-profile Chatham, American Media has become a high-profile headache. After sparking federal prosecutors’ ire for its role in burying Trump’s secrets shortly before the 2016 election, the company has drawn international attention for its war with Jeff Bezos over its exposé of his extramarital affair.

Chatham’s tabloid publisher possesses a “treasure trove” of Trump’s secrets, his former fixer Cohen told Congress last month.

Pressure has been building. New Jersey, which has generated a more-than 12 percent annualized return on its investment, is entitled to withdraw $355 million from one of Chatham’s funds at the end of this year. The state has said it’s exploring its options in light of Bezos’s claim that American Media tried to blackmail him.

The California state pension system has been planning to exit all of its hedge fund investments and has been asking Chatham to sell holdings so it can return about $200 million.

Chatham investors say that even if authorities go after the National Enquirer for allegedly extorting Bezos or for catch-and-kill tactics, American Media is a valuable company, with several magazines it could sell to raise money for creditors.

Grimstad knows what it’s like to be under a tabloid-like glare. While he was wrangling with Chatham, news trucks were parked outside his house for days. The ugly litigation with the tech executive was resolved with a less-than-remorseful apology and a multimillion-dollar payday for Grimstad.

“The company regrets any distress that may have been caused to the Grimstads by the public filing of the litigation against them,” Chatham-controlled iPayment said at the time.

--With assistance from Neil Weinberg and Matt Robinson.

To contact the reporters on this story: Katherine Burton in New York at kburton@bloomberg.net;Sridhar Natarajan in New York at snatarajan15@bloomberg.net;Shahien Nasiripour in New York at snasiripour1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Caroline Salas Gage at csalas1@bloomberg.net, ;David Gillen at dgillen3@bloomberg.net, David Scheer

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.