At 3 p.m., Trading in U.S. Bond Futures Jumps Like Clockwork

At 3 p.m., Trading in U.S. Bond Futures Spikes Like Clockwork

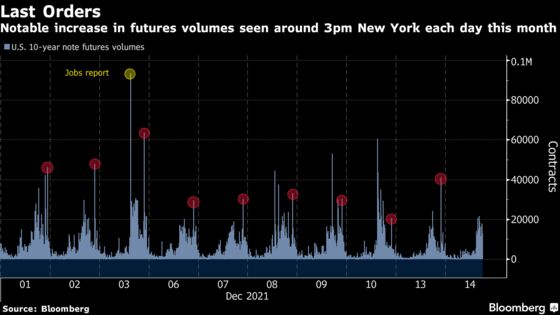

(Bloomberg) -- It happens like clockwork: Trading volume in Treasury 10-year note futures spikes at around 3 p.m. New York time, often to the highest level of the day, only to fade away just as quickly.

While the pattern is common at month-end, it has become a near-daily occurrence over the past month. The hour corresponds to the settlement time for U.S. government bond futures, suggesting that the activity stems from asset managers rebalancing portfolios.

The pattern is attracting attention as flummoxed investors seek the source of relentless demand for long-term bonds despite the fastest inflation since the 1980s. A leading thesis is that pension funds -- which thanks to U.S. stock market gains are nearly fully funded for the first time since 2008 -- are taking profits and using them to buy bonds.

Read More: Morgan Stanley Finds Signs of Pensions Flattening Yield Curve

A study by Morgan Stanley published Friday found that over the past year, 30-year Treasury yields and stocks declined in tandem “pretty materially” between 3:30 p.m. and 4 p.m. New York time, the end of trading day. Rebalancing by pension funds is the likely reason, and it has flattened the yield curve, strategists led by Matthew Hornbach concluded.

The end-of-the-day price action “seems consistent with our assessment that as funded ratios had begun to improve in the last twelve months, these pension plans were rebalancing by selling equities and buying long-duration fixed income,” the strategists wrote. “Demand from defined benefit pension funds is having a major impact on long-end Treasury yields, and putting bull-flattening pressure on the curve.”

Persistently low long-maturity bond yields are puzzling because inflation has surged. The 10-year note’s yield was around 1.44% Tuesday, far below the 6.8% year-on-year increase in consumer prices in November. The 30-year yield fell below 1.7% earlier this month to an 11-month low, before rebounding to 1.82%.

But the U.S. stock market’s foray to record levels has lifted pensions’ funded ratio with respect to their liabilities to 99% this year, near the highest in more than a decade, according to Milliman. Pension funds tend to match their liabilities -- which are usually long-term -- with similar-maturity debt.

“Pension demand is a structural bid in the long-end” of the yield curve, said Priya Misra, global head of interest-rate strategy at TD Securities, in an interview. In a note last week, she pinned the decline in long-term bond yields on purchases by banks, pensions and China.

Pension demand could weigh on long-term yields even as the Federal Reserve tightens monetary policy, recalling the state of affairs in 2004 that then-Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan famously called a conundrum. The Fed, which started a two-day policy meeting Tuesday, is expected to accelerate the reduction of its asset purchases to pave the way for interest-rate increases next year.

Morgan Stanley strategists in a separate report last month estimated that pensions funds, with total assets in excess of $3.5 trillion, could add $150 billion to $250 billion of fixed-income assets over in the next 12 months, on course for the biggest flows since the global financial crisis. Their demand could “flatten the curve more than normal for a rate hike cycle,” they wrote.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.