As Fed’s QE Era Ends, a New Trillion-Dollar Bond Dilemma Emerges

More than a decade after it all began, the Federal Reserve is finally nearing the end of its grand experiment in monetary policy

(Bloomberg) -- More than a decade after it all began, the Federal Reserve is finally nearing the end of its grand experiment in monetary policy.

The Fed, which has been paring its crisis-era debt holdings, may lay out plans to end the program at its meeting next week. Yet in the Treasury market, the close of the quantitative-easing era could open another can of worms.

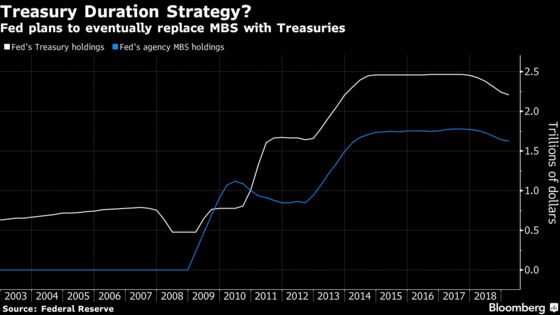

While Fed officials have made it clear they want to go back to owning mostly Treasuries, as they did before the financial crisis, it’s unclear how the central bank will get there or what it will buy. Its current policy, replacing mortgage bonds only when they mature, could take a decade or more. That’s led some to advocate outright sales, which the Fed has never done. Then, there’s the debate over whether the central bank will favor short-term Treasuries over long-term debt, or simply buy whatever the U.S. Treasury auctions off.

“People are way too focused on when the Fed is going to end the balance-sheet shrinkage,” said William Dudley, former head of the New York Fed, who is now a professor at Princeton University. “That question is actually pretty trivial relative to the question of what is the Fed’s balance sheet going to look like over the long run.”

The consequences could ripple through the bond market and beyond. Decisions affecting the composition of the Fed’s balance-sheet assets will not only create winners and losers across financial markets, but could also go a long way to help the U.S. government finance its burgeoning budget deficit.

Currently, the Fed holds just a little less than $4 trillion in assets and is paring its bond holdings by a maximum of $50 billion a month. Bond dealers expect the Fed to end its runoff by December, which will leave it with roughly $3.5 trillion to $3.7 trillion in assets.

One important thing to understand is that the Fed needs to continually add Treasuries to replace those that come due just to keep the size of its balance sheet constant. That means it will need to ramp up purchases even more as it shifts away from mortgage bonds. (As an aside, analysts also see the Fed’s balance-sheet assets gradually starting to grow again in a year or so. If they don’t, the steady rise of dollars in circulation on the liability side of the ledger will squeeze bank reserves, which have already fallen in recent years.)

Two Ways

The Fed reinvests money from its maturing debt holdings in two ways. When replacing Treasuries, it participates in so-called auction add-ons, which enable the central bank to purchase debt alongside the public to finance U.S. government spending. So, the more debt the Fed gobbles up, the less money the U.S. Treasury needs to raise at auction. When replacing MBS, it buys debt directly from investors in the open market (more on that later).

For many bond dealers, the Fed’s Treasury purchases at auction will help the government scale back bill issuance. Citigroup also predicts 2-to-5-year note auctions will shrink later this year as a consequence of increased Fed demand.

“The most important impact for the bond market will be that the Treasury’s net marketable borrowing needs from the public will decline,” said Margaret Kerins, global head of fixed-income strategy at BMO Capital Markets.

BMO, which predicts the unwind will end in the third quarter, says demand from the central bank will reduce the Treasury’s public borrowing needs by about $350 billion in the ensuing 12 months. For context, that figure equals roughly 44 percent of the U.S. government budget deficit for fiscal year 2018.

Big Winner

Seth Carpenter, chief U.S. economist at UBS, also sees bills as a big winner. By law, the Fed will be required to buy Treasuries directly in the open market (rather than at auction) when the money comes from maturing MBS. Bills and short-term notes give the Fed the greatest flexibility. The money can be reinvested sooner, and at auctions, if it chooses.

“I fully expect the Fed to focus those purchases in the front end,” said Carpenter, who’s worked at both the Fed and the Treasury.

Because the Fed currently doesn’t own any bills, the weighted average maturity of its Treasury investments is about eight years. That compares with 5.8 years for the market itself. Minutes from its December meeting showed that participants discussed either matching the portfolio’s average maturity to the market’s (for a “more neutral effect on the market”) or to shorten it (for “greater flexibility to lengthen maturity” if needed in a downturn).

Right now, the Fed doesn’t actively manage the composition of its holdings and allocates its add-ons in proportion with the amounts the Treasury auctions.

Outright Sales?

Blake Gwinn at NatWest Markets says the open-market purchases will be “a big deal.” They will likely push short-term rates down relative to long-term yields, steepening the yield curve, which has been flattening persistently for years.

To get to its all-Treasuries goal, Dudley says the Fed should seriously consider outright sales of MBS to meet its monthly cap of $20 billion, which it rarely hits now. Last month, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell said on Capitol Hill that such sales were at the “back of the line” when it came the central bank’s thinking.

Regardless, the Fed’s shift away from mortgage bonds could present a risk for the MBS market if 10-year Treasuries -- the benchmark for 30-year mortgages in the U.S. -- fall below 2.25 percent, according to Walt Schmidt, head of MBS research at FTN Financial. Those levels could trigger an influx of supply as lower rates prompt homeowners to refinance their mortgages.

“There will be no Fed to sop up supply,” he said.

For now, all eyes are on the Fed’s two-day gathering, which starts March 19.

“The Fed really needs to get into these details soon,” said Joseph Gagnon, a former Fed official, who is now a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics. “It’s the dog that hasn’t barked.”

--With assistance from Christopher Maloney.

To contact the reporters on this story: Liz Capo McCormick in New York at emccormick7@bloomberg.net;Alexandra Harris in New York at aharris48@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Benjamin Purvis at bpurvis@bloomberg.net, Michael Tsang, Kara Wetzel

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.