A Hedge Fund, a Bond Default and a College’s Fight to Survive

A Hedge Fund, a Bond Default and a College’s Fight to Survive

(Bloomberg) -- The fate of a Florida college founded by a black civil rights activist may be in the hands of a California hedge fund.

That’s because Lapis Advisers, a distressed debt investor, is the biggest single holder of about $17 million of bonds sold by Bethune-Cookman University, a 115-year-old school in Daytona Beach contending with mounting losses, declining enrollment and a troubled dormitory project whose soaring costs led to a court fight over allegations of fraud.

In January, U.S. Bancorp, the bond trustee, warned that the housing project pushed the university’s debt above the caps contained in the securities contract, triggering a default. As a result, investors can demand early repayment of the bonds, which the junk-rated school can’t afford to do. Instead of invoking that right, Lapis has been negotiating for possible concessions that included, at one point, a request for power over campus real estate worth about $160 million.

“What they have engaged in is basically extortion, in my estimation,” said Belvin Perry, chairman of the university’s board of trustees. “What you’re doing is basically tearing down an institution that is designed to help diamonds and unpolished diamonds in the black community.”

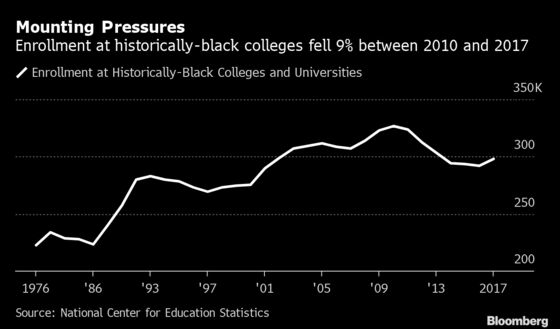

Bethune-Cookman, with some 3,700 students, is the latest historically black college to run into deep financial troubles as small schools nationwide struggle to boost enrollment. After surging for decades, the number of students at black colleges fell 9% from 2010 through 2017, a bigger drop than what other degree-granting institutions saw over that time, according to U.S. Department of Education statistics.

Faced with that squeeze, Concordia College Alabama, a private Christian school in Selma, Alabama, closed in spring 2018. Bennett College, a black liberal arts school for women in Greensboro, North Carolina, relied on a student and alumni fundraising campaign to stay open amid threats to its accreditation status.

Janelle Williams, a visiting scholar at the Rutgers Center for Minority Serving Institutions, said historically black schools tend to lack the fundraising resources that larger ones can draw upon. They “have already had to do more with less,” she said.

Bethune-Cookman, started as a vocational school for five black girls in 1904 by Mary McLeod Bethune with an initial investment of $1.50, became accredited as a junior college in 1931. It received university status in 2007 and is popular among students for the nursing, business administration and criminal justice programs.

But it has recently struggled. Enrollment dropped by about 8% in 2018. The same year, it was warned its accreditation could be revoked, in part because of the mounting financial pressure. Contending with budget shortfalls, it has steadily drawn down its assets, leaving the university’s auditor expressing doubt about whether it can remain open. Trustees in June moved to use $8.5 million from its endowment to cover day-to-day costs.

Pressure Point

Kjerstin Hatch, the founder and managing principal of the Larkspur, California-based Lapis, said the firm wants to see the university survive by coming up with a solution to “a fairly significant default on their part.”

“They may think it’s overreaching, they may think its bullying,” she said. “We’re working really hard to try to ensure the future success of this important institution.”

The default on the 2010 bonds stems from a dormitory project that has become a huge pressure point.

After the cost roughly quadrupled from initial estimates to more than $300 million, the university last year sued the developer, TG Quantum, and the school’s former president, Edison Jackson. The developer responded with a lawsuit of its own in February 2018 seeking damages and to have a receiver placed in charge of the dorm.

The school’s bonds have plunged to about 54 cents on the dollar, even though it has continued to make interest payments. Fitch Ratings said in a report in May that it didn’t think that Bethune-Cookman had the resources to pay off the bonds early if investors invoke those rights.

$595 Per Hour

Then last week, trustee U.S. Bancorp said in a regulatory filing that the school may have breached another term of the bond contract when university leaders approved the borrowing from the endowment.

To avoid facing accelerated debt payments, Bethune-Cookman has been negotiating with Lapis. But the university’s leaders say the firm’s demands have been excessive. U.S. Bancorp and Lapis asked for a first mortgage on the university’s property as part of a forbearance agreement that would last until December, said Perry, the Bethune-Cookman board chairman. He said the property is worth about $161 million, much more than what’s outstanding on the bonds.

They also proposed temporarily installing a coordination officer, which Perry called a “shadow” role that would allow the fund to try to influence the university.

The university has also been sparring with U.S. Bancorp, which said it has been unwilling to pay the bank’s fees and expenses. An invoice for $221,280.18 lists legal fees as high as $595 per hour. Bethune-Cookman said in a July 26 letter that the trustee hasn’t given enough detail on the charges, such as why it was spending resources researching bankruptcy, a step that the school isn’t considering.

Cheryl Leamon, spokeswoman for U.S. Bancorp, declined to comment.

Perry, a former judge who oversaw the sensational 2011 trial of Casey Anthony -- who was found not guilty of murdering her 2-year-old daughter -- said the bank has picked the “wrong group” to pick a fight with.

“They come in and buy low and try to get as much money as they can and move on,” Perry said. “Well, guess what? This school was founded by Mary McLeod Bethune, with $1.50 and built on the site of a dump, to educate people of every hue.”

“There was some mischief in the past and we’re litigating these things now,” he added. “But yes, we have fulfilled our obligations.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Amanda Albright in New York at aalbright4@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Elizabeth Campbell at ecampbell14@bloomberg.net, William Selway

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.