European Taxpayers Once Again Are Bailing Out Bankers

European Taxpayers Once Again Are Bailing Out Bankers

(Bloomberg) -- The promise to European taxpayers after the financial crisis was simple: No longer would they be the first to be asked to rescue failing banks; instead, investors should pick up the bill when a lender goes down.

“Taxpayers no longer in front line to pay 4 banks mistakes,” tweeted Michel Barnier, then the European Union’s top official for financial regulation, on a December night in 2013 when political negotiations on the new legislation wrapped up.

Fast forward six years, and the public is trying to keep up with all the ways in which governments have managed to circumvent this principle. Just this month, the European Commission approved Germany’s 3.6 billion-euro ($4 billion) rescue of Norddeutsche Landesbank-Girozentrale, while Italy is busy engineering a bailout of a regional lender in the country’s South.

“We could not be more worried; this might have been the last nail in the coffin of our resolution framework,” Luis Garicano, a Spanish member of the European Parliament for the liberal group, said in an email.

After the crisis, the EU agreed on a set of rules meant to shift the burden to owners and creditors of troubled banks, forcing them to take losses before a bank is allowed to use public funds. An agency was created to deal with failing banks in the euro-area and lenders are required to issue certain kinds of debt that can be converted into equity or written down in case of a problem.

Since the framework fully took effect in 2016, its shortcomings have become increasingly obvious. The Single Resolution Board, the euro-area’s failure agency, only handles the very biggest cases, while the rest is dealt with under national insolvency rules. These are very different from each other and can open doors to public rescues.

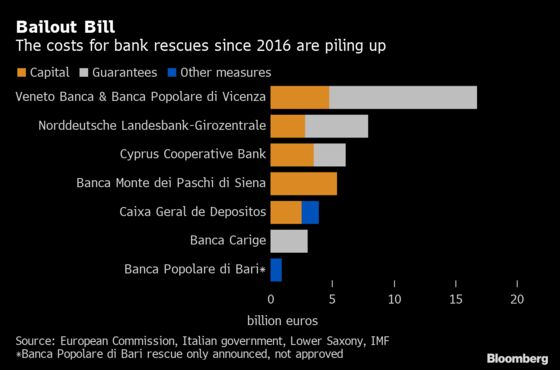

Taken together, the experience highlights how allergic governments still are to ceasing control of a failing bank to an EU institution, and how specific circumstances make it politically undesirable to apply the most drastic parts of the toolkit. Here are the most important cases in which taxpayers were put on the hook for bank rescues since 2016:

Banca Popolare di Bari

In the most recent example, this regional lender in Italy’s south racked up non-performing loans exceeding “every acceptable measure,” according to Chief Executive Officer Vincenzo De Bustis. The government agreed to set up a development bank, provide it with 900 million euros, and let it fund the restructuring of Banca Popolare di Bari SCpA, together with interbank fund FITD. With total assets of less than 14 billion euros, the bank is too small to be supervised by the European Central Bank or the Brussels-based SRB. As with previous cases of troubled Italian banks, imposing losses on investors of the bank is politically fraught, because many of its liabilities were sold to retail clients, also known as voters.

NordLB

Northern German lender NordLB got the EU’s green light for a rescue involving 2.8 billion euros in capital injections as well as about 5 billion euros in guarantees this month after its funds were eroded by toxic shipping loans. The burden is divided between two German provinces as well as publicly owned savings banks. The rescue was preceded by negotiations with Cerberus Capital Management and Centerbridge Partners over a stake in the bank, but the owners -- the states of Lower Saxony and Saxony Anhalt as well as some public savings banks -- ultimately decided to prop up the bank themselves. The commission decided that no illegal state aid was involved because investors are remunerated “on market terms,” meaning that a private investor would, at least in theory, accept the same conditions. If there was a private investor who would accept such terms, it certainly didn’t show up.

Banca Carige

Held back by management conflicts and non-performing debt, Banca Carige SpA lurched from crisis to crisis and was put under ECB administration at the beginning of this year in an unprecedented move. The government provided liquidity guarantees to the tune of 3 billion euros in January to make sure that the bank can continue paying its liabilities. The commission’s state aid department argued that the support is in line with its rules because Carige is paying a fee to the sate and because the measure is “targeted, proportionate and limited in time and scope.”

Veneto Banca and Banca Popolare di Vicenza

After Italy tried for months to find a solution for the floundering banks in one of the country’s richest regions, the ECB pulled the plug on them on a Friday night, in June 2017, handing them over to the SRB for disposal. Crucially, the agency decided they weren’t important enough to warrant special treatment known as resolution and passed the baton to Italian authorities. They in turn committed as much as 17 billion euros in liquidation aid to avoid a “serious disturbance” in the local economy and to support a takeover by Intesa Sanpaolo SpA. While shareholders and junior creditors took losses in line with EU state aid rules, Italy later decided to reimburse the vast majority of them, claiming they had been mis-sold by the two banks. The commission’s state-aid department has supported all of these measures.

Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena

Italy seized on an exemption in the EU bank failure rules -- known as Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive -- to inject 5.4 billion euros into the world’s oldest bank, which had been struggling with a mountain of bad loans. A section of the law allows governments to provide a precautionary recapitalization to solvent banks, in order to remedy a “serious disturbance” in the economy. Again, shareholders and junior creditors took losses, though retail customers could seek compensation from the bank. As in the case of the two Venetian banks, senior bondholders were spared. The state now owns 68% of the bank and is exploring ways to dispose of the holding.

Caixa Geral de Depositos

The 2017 recapitalization of this fully state-owned Portuguese lender also wasn’t considered illegal state aid because, much like in the case of NordLB, the capital was provided by the government on “on market terms.” Portugal invested 3.9 billion euros while planning a deep restructuring of the bank to safeguard its long-term profitability. In November, CGD reported net income for the first nine months of 641 million euros, and the government expects to receive a 237 million-euro dividend next year.

Cyprus Cooperative Bank

Cyprus won EU approval in 2018 to shell out 3.5 billion euros, more than 10% of its gross domestic product, for the wind-down of the nation’s second-biggest lender. The main reason the commission went along was that this was such a long-running case, started before the EU’s resolution regime took effect, that it should be handled on the basis of national laws. Half of the bank’s assets were nonperforming and it was funded entirely through deposits, meaning there were no bondholders that could have contributed to the costs of its failure, according to the commission.

--With assistance from Stephan Kahl, Joao Lima and Paul Tugwell.

To contact the reporter on this story: Alexander Weber in Brussels at aweber45@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Dale Crofts at dcrofts@bloomberg.net, Nikos Chrysoloras, Christian Baumgaertel

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.