Why Chronic Profit Shortages Mean Most Stock Prices Can't Be Justified

Why Chronic Profit Shortages Mean Most Stock Prices Can't Be Justified

(Bloomberg) -- Wait long enough, and companies will earn enough to justify their stock prices. It’s an appealing premise in a market as richly priced as this. But a new study claims it’s wrong.

While a few standout firms do grow into valuations, the typical public company fails to generate discounted earnings over its lifetime equal to the value of its shares, according to researchers at Cornell University and Columbia University. They used the benefit of hindsight to trace corporate income over four decades and found, in effect, that that corporate earnings are a worse risk-adjusted bet than interest on a 10-year Treasury note.

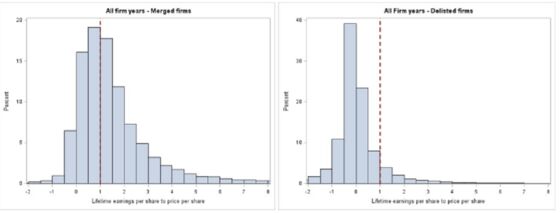

The news wasn’t all bad for bulls. According to the paper, titled “Lifetime Earnings,” stock owners regularly get bailed out in the end by takeovers that occur at equally extreme valuations. The authors, including Sanjeev Bhojraj and Ashish Ochani from Cornell and Shiva Rajgopal from Columbia, framed their findings as an investigation into “errors in earnings expectations.”

Stocks “see higher and higher prices because the goalpost is constantly moving, and people are constantly looking into the future and think, ‘Oh, this company is going to own the world,’” Bhojraj, alumni professor in asset management, said in an interview. “What we’re showing is, that really doesn’t happen for the most part.”

While the findings suggest investors make mistakes when assessing earnings, and the authors link those errors to violent corrections like the ones in 2000 and 2008, the study is not in and of itself a real-time sell signal. Hope springs eternal in bull markets -- hope for a takeover, hope that a favorite company will buck the trend -- and even against long odds investors persist in believing they can find winners.

The study joins a growing body of research depicting the broader stock market as overrun with dud companies that don’t live up to the hype with which they’re brought to market. Previous papers by Hendrik Bessembinder of Arizona State University focused on price returns among individual stocks over very long periods, and found the majority similarly fail to exceed Treasury bonds.

“If it were a roulette wheel, it would be a situation where you don’t have an equal number of black and red slots,” said Lawrence Creatura, a fund manager at PRSPCTV Capital LLC. “That’s the nature of the stock market. Most stocks do underperform, statistically speaking, and it is a minority that outperform and a small minority that really drive excess performance.”

According to the Cornell and Columbia paper, so richly valued are newly issued shares that the average firm saw its first-day stock price exceed its discounted lifetime earnings by 67%, according to the study.

A related finding is how few companies manage to stay independent over time. A lot get acquired, others go bankrupt, and others are delisted. In 45 years of data that the scholars studied, only 17% of the firms avoided these fates.

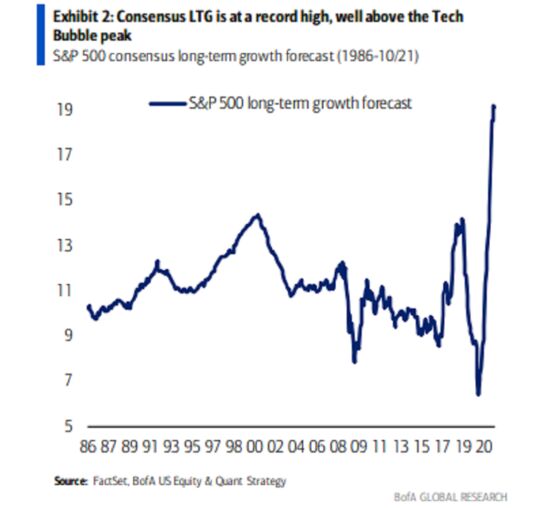

Right now, U.S. markets are trading by many measures at the highest valuations in two decades. Long-term profits from S&P 500 companies are expected to expand 19% a year, a pace that’s well above the peak seen during the dot-com era, data compiled by Bank of America Corp. showed.

“People are not paying attention to fundamentals as much as they should, maybe because of ETFs, maybe because of indexation,” said Rajgopal, a professor of accounting and auditing. “Unfortunately, our finance colleagues blindly believe in efficient markets. So it’s religion, partly because they don’t care to look at fundamentals.”

The researchers started with a question: What’s the worth of a company’s total income over its lifetime at the time of its first day of trading, and how does that compare to the initial share price?

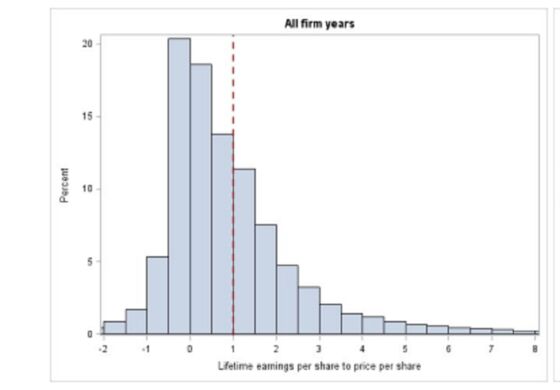

To answer, earnings for some 16,000 companies were collected from 1975 to 2019 and discounted back to the first day for each firm. The scholars used 10-year Treasury yield plus an equity risk premium of 5% as the discount rate (a calculation they viewed as conservative but which others might consider otherwise). The so-called lifetime earnings were then set side by side with the first-day share prices to derive at a long-term earnings ratio. The data also includes spinoffs and direct listings.

To be sure, some companies succeed in generating earnings equal to or exceeding their share prices, a phenomenon that has been used to explain the striking performance of high-valuation tech stocks in recent years. Even among the vaunted Faang bloc, however, the difference between hitting the mark and missing it is often vanishingly small.

Take Amazon.com Inc., the online giant that went public in 1997 at a split-adjusted price of $24. By 2019, the retailer had amassed earnings equal to $53 a share in 1997’s value -- roughly 2.2 times its IPO price, so a relatively positive outcome. Still, the authors noted, 18 years is a long time to wait for earnings to catch up.

Amazon was a rare standout. The study found the average company’s long-term earnings ratio was only 0.2, meaning for every $10 spent originally on the stock, only $2 were eventually delivered in terms of profits by 2019.

Stripping out companies that for one reason or another ceased to exist as independent concerns improved the outcome. The surviving firms generated a ratio of 0.7, though their profits still fell short of what investors spent on their shares at the very beginning. Adding in an adjustment to project hypothetical earnings out many years also enhanced the ratio.

It wasn’t until takeovers were taken into account that the ratio reached 1, a threshold that according to the scholars indicated the market’s initial pricing was backed up by fundamentals.

So what do investors do knowing the market has a tendency to overvalue earnings? To the researchers, the mispricing offers opportunities. Ranking stocks by the ratio of lifetime earnings versus share prices at the start of each year, they found that a strategy that buys the top decile and sells the bottom decile outperforms in the following 12 months.

“The market pricing is a fraud and what you do see is that at some point there is a reckoning,” said Bhojraj. “When your stock is overvalued, you just have to hope that some people buy you” out, he added. “It’s not because those are good firms. It’s because that’s where you get lucky.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.