Leveraged-Loan Investors Can’t Feign Gullibility

Leveraged-Loan Investors Can’t Feign Gullibility

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Investors in the $1.2 trillion leveraged-loan market are not naive. In fact, by design, syndicated loans are offered only to qualified, accredited buyers, precisely the types of firms that have the analytical firepower to determine whether they should step in and lend to inherently risky companies.

Even the smartest investors know that every once in a while, they’re bound to get something wrong in a lightly regulated market where it seems as if mostly anything goes.

It turns out it’s one thing to understand that conceptually. But it’s entirely different to actually get burned.

As Bloomberg News’s Lisa Lee reported last week, a group of buyers is suing JPMorgan Chase & Co. and other Wall Street banks, accusing them of securities fraud in a $1.8 billion leveraged-loan deal from Millennium Health LLC in April 2014. Some 70 institutional investor groups bought into the offering from the largest drug-testing lab in the U.S., according to the lawsuit, only to see much of their money wiped out after the company disclosed that federal authorities were investigating its billing practices. JPMorgan knew that when it priced the loan but didn’t tell prospective investors because Millennium said it wasn’t material at the time, according to previous Bloomberg reporting. Millennium eventually went on to declare bankruptcy.

It’s quite the tale, and one that has developed over several years. The punchline, though, is that leveraged loans aren’t actually “securities,” meaning the whole exercise might be entirely futile:

The defendants say there’s one key problem -- unlike bonds, loans aren’t securities. As a result, they’ve filed a petition asking the court to dismiss the suit on those exact grounds.

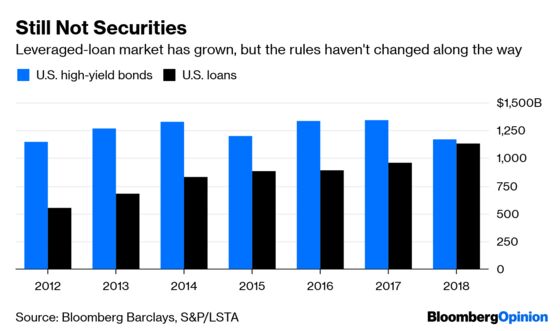

The debate strikes at the heart of the leveraged loan market, which in recent years has come to look markedly similar to the higher-profile one for junk-rated bonds. The standardization of loan terms, the deterioration of covenants and the growth of secondary trading continue to blur the lines between the two. Should the plaintiff ultimately prevail, it would dramatically alter how American companies raise debt, according to two industry groups that filed a brief supporting the defendants’ argument last week.

…

“The sophisticated entities that lent Millennium money now try to classify the loan as a ‘security’ and the loan syndication as a ‘securities distribution’ in an attempt to manufacture a securities fraud claim where none is viable, and to avoid the express language of the contracts into which they willingly entered,” JPMorgan and Citigroup wrote in a memorandum last month.

I’m hard pressed to come up with a counterargument to that. There’s no question that leveraged loans and high-yield bonds look more alike than in the past, but why would that give investors the right to change the rules retroactively? In fact, lenders have historically relied on confidential, nonpublic information when determining whether to participate in a leveraged-finance deal precisely because the disclosure requirements are known to be minimal. Call the behavior of Millennium and the banks unethical if you must, but that’s far different from contending they acted illegally.

In Bloomberg’s July 2015 report, which revealed how much JPMorgan knew about Millennium’s troubles in advance, a credit-rating analyst lamented that “it’s very, very frustrating from the perspective that you don’t know how much more they know that they’re not telling you.” But in the same article, a money manager duly noted that “balance of power is with the issuer” in leveraged loans, and “you have to be vigilant in what you’re buying.” Let those two comments sink in for a moment. Even four years ago, one side sounds whiny and the other sounds levelheaded.

That won’t matter if the courts determine leveraged loans should be classified as securities. It’ll probably take years to shake out, even if judges side with the spurned investor group. But in an extreme scenario in which the law changes to deem leveraged loans as securities, the ramifications would be enormous. The Loan Syndications and Trading Association and the Bank Policy Institute cited two chief consequences. First, arranging a loan deal would take longer because of stricter disclosure, potentially causing some borrowers to shy away from financing altogether. Second, banks aren’t allowed to buy collateralized loan obligations that own securities, meaning a rule change could spark $86 billion of forced CLO selling.

It’s fair to question whether leveraged loans need more oversight. Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, the Federal Reserve, the International Monetary Fund and the Bank for International Settlements are among those who have sounded the alarm over the market’s explosive growth. But a wholesale change to the rules just because a few big investors suffered losses on one deal isn’t the way to do it. There are enough smart people on both sides that they could probably find some middle ground and come up with common-sense changes.

If not, then let them be adversarial. Anyone buying leveraged loans at this point should be going in with eyes wide open. Don’t hate the banks and the borrowers, hate the market.

For what it's worth, the plaintiffs say the case is “not a referendum on the application of federal or state securities law” to leveraged loans generally but solely about the Millennium deal.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.