How an Esports Queen Trounced Billionaire Heirs

How an Esports Queen Trounced Billionaire Heirs

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- That esports players and company founders are showing up alongside biotech entrepreneurs at snazzy investor conferences can mean only one thing: Competitive video-gaming is going mainstream.

That’s a good thing for game publishers, who have come to recognize esports tournaments as a marketing opportunity. League of Legends, a nine-year-old title — ancient by industry standards — generated $1.4 billion in sales in 2018 for its owner, Tencent Holdings Ltd. Last year, four of the top six esports titles by prize money (which can reach into the millions) were among the top 20 highest-grossing games.

Success doesn’t come cheap, though. Over the past year, Tencent plowed more than $1 billion into China’s top two video-game live-streaming platforms, Douyu and Huya Inc. Both are burning through cash at lightning speed.

When there’s real money to be made, speculative dollars start to flow. Invictus Gaming, the Chinese team that won the League of Legends world championship in November, is owned by Wang Sicong, the flamboyant son of Wang Jianlin, chairman of Dalian Wanda Group Co. and once China’s richest man. Zhu Yihang, son of Hopson Development Holdings Ltd.’s founder, owns another club called EDG.

That makes the success of Pan Jie, who founded LGD-Gaming in 2007, all the more striking. The shy, 32-year-old single mom doesn’t come from billionaire parents. Yet somehow Pan Jie — dubbed “the Queen” among professional players of Dota 2, one of esports’ most popular titles — has managed to build China’s largest esports club.

The studious daughter of a small-time businessman in the port city of Nantong in Jiangsu province, Pan Jie started hanging out at internet bars during her university days. Skipping classes to play video games gave her a rush of rebelliousness, she says, particularly after her regimented high-school schedule. Though gaming felt a bit foreign at first, she eventually fell in love with multi-player titles for the discipline and training they required.

That competitiveness will continue to serve her well. Like professional basketball and other mainstream athletics, esports clubs shell out huge sums to buy top players — as much as $1 million or more. This adds up quickly for games like Dota 2, which requires five gamers. Rich competitors can easily lure away top players, though even transfer contracts earn money. LGD got 15 percent of its income from such swaps last year.

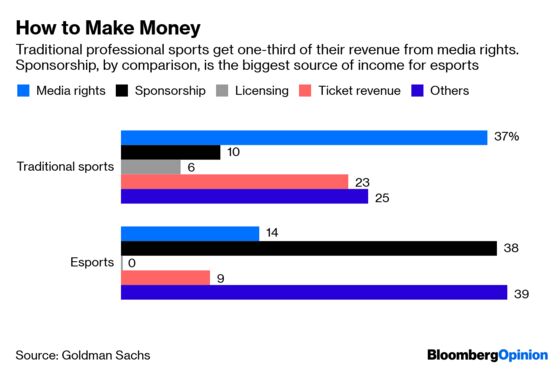

With players taking home 90 percent of tournament prize money, clubs need to start thinking about how to monetize, whether through sponsorships or media rights. Even those backed by wealthy heirs have to obey the laws of economics these days, Pan Jie said at last week’s Bloomberg Invest Asia conference.

To navigate this hypercompetitive landscape, LGD has opted to develop its own farm team. Professional coaches — retired pro players, often not a day over 30 — sift through millions of amateurs online. Yuhang Guo — a 22-year-old nicknamed Eve, who live-demoed at the Bloomberg conference — is one such cub, with an “immortal” 8000 matchmaking rating in Dota 2. The club also created a profitable app — VPGame — to sell live predictions of which players will win.

Esports isn’t for the fainthearted. In March, Panda TV, China’s third-largest game-streaming network owned by Wang Sicong, entered bankruptcy. Hedge funds rushing into Huya or Douyu’s impending IPO would do well to remember that.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Rachel Rosenthal at rrosenthal21@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Shuli Ren is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Asian markets. She previously wrote on markets for Barron's, following a career as an investment banker, and is a CFA charterholder.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.