We’re Living in What May Be the Most Boring Bull Market Ever

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- To the extent anyone on Wall Street cares—and many will tell you they don’t—records in stocks are good for one thing: advertising. Talk all you want about rates of return or piling it up for retirement, but nothing beats a headline about an all-time high for bringing customers in the door.

And in they have come. Cheered by what’s become by some measures the longest bull market on record, U.S. investors have plowed money into U.S. stock exchange-traded funds at a rate of almost $12 billion a month since the start of 2017, five times as much as seven years ago. There are signs of stress—like the recent sell-off in Asia—but so far they appear in U.S. investors’ peripheral vision. Anyone buying stock in an American company right now must be comfortable paying two or three times annual sales per share, a level of shareholder generosity that hasn’t been seen since the dying throes of the dot-com bubble.

When we tell our grandchildren about this bull market, we’ll start by describing its demise, in the crash of 2019, or 2020, or 2025. But we don’t know the end of this story yet. What will we say of the rest? That dips were bought and passive investing ruled, perhaps, and that a handful of tech megacaps—most of them decades old—grew to planetary size. But if the decade is remembered for anything, it could also be as the era when equities returned close to 20 percent a year on average from the March 2009 bottom and the stock market, somehow, got boring.

Which is to say, this isn’t like the boom of the late 1990s. Rarely do companies have initial public offerings where their stocks double on the first day of trading. The tip-dispensing cabbies of the bubble era are driving Ubers now, and any money they have to invest is going into ETFs, not individual stocks.

That’s what it’s like now: a market with fewer human voices, where the hum of computers is the background music to math projects with names like smart beta and risk parity. It’s a land ruled by giants. Three, to be exact—Vanguard, State Street, and BlackRock, which manage 80 percent of the $2.8 trillion invested in U.S. stock ETFs. IPOs, once the life of the market party, have turned into inconveniences in a world dominated by passive funds, occasions for reordering delicately balanced indexes.

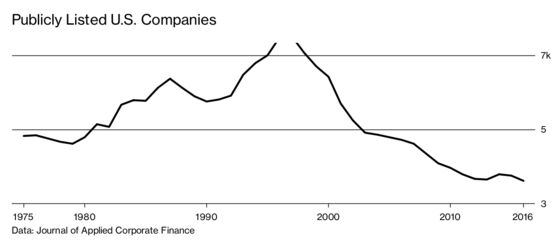

In any case, companies are staying away from public markets in droves. From an annual rate of almost 700 new listings in the last half of the 1990s, the average has fallen 75 percent. While deals are up from last year and hope is running high that the spigot will open again, such expectations have been repeatedly dashed. “What we are really witnessing is an eclipse not of public corporations, but of the public markets as the place where young successful American companies seek their funding,” says a recent study by academics Craig Doidge, Kathleen Kahle, G. Andrew Karolyi, and René Stulz. They found there were 11 public firms for every million Americans in 2016, compared with 22 in 1975.

There’s no shortage of theories on what’s causing this, spanning everything from old-fashioned accounting rules to how the internet has made it easier to raise money from private investors, but the hardships of being a public company are frequently cited as the main culprit. While retail investors may have put more of their money on autopilot, hedge funds and other big investors seeking to carve out an edge can still make the life of a chief executive officer miserable. The number of so-called activist investors making demands on public companies swelled past 500 for the first time in the first half of 2018. That’s nearly double the level of five years ago, according to research consultant Activist Insight.

Few topics get the pros’ dander up like this one. If you’re looking for an anomalous era, look at the 1990s, when every 22-year-old with a Java compiler ran a half-billion-dollar company. People paid dearly for euphoria back then. If the market is more discriminating today, good for it.

Still, the market’s image has dimmed. It’s seen by many as a channel for social blight. Companies may spend a trillion dollars this year on share repurchases—money that critics say should be used to build factories and create jobs (though those investments are up, too). People sense they’re getting screwed as all the country’s economic bounty flows to the top. At times in the past 10 years, the difference between annualized returns in the S&P 500 and growth in wages has been the widest for any bull market since the Lyndon Johnson administration.

Ten years after the worst meltdown since the Great Depression, all this is preventing rehabilitation of the idea of public company stewardship. If the sweet spot for entrepreneurship is somewhere around 30 years old, today’s best and brightest is an age cohort that graduated into the financial crisis. While this group’s Gen X forebears may remember a time when markets could be fun, now they’re a drag, a cesspool of high-frequency traders and at chronic risk of tipping over. What’s the point of going public when venture firms will hand you all the money you want?

That’s the big change: access to capital that doesn’t require a public listing. Right now, venture firms have about half a trillion dollars under management, roughly equivalent to all the money raised in IPOs over the last 10 years. Companies that would’ve gone public within a few years of being created in the 1990s aren’t even thinking about it now.

Disdain for public markets reached a kind of apotheosis last month with the story of Tesla Inc. CEO Elon Musk’s dalliance with going private. Tesla sits at the fulcrum of many of these market strains. Up about 40 percent a year since 2010, it’s a relatively recent IPO upon which the market confers a princely valuation. It’s also a favorite target of short sellers, who bet on the price of a stock falling, to the point where Musk was willing to forgo all the benefits he gets from public markets and consider leaving them. Technology companies trading at 100 times next year’s earnings didn’t used to consider going private. Apparently, they do now.

There’s talk of making markets more friendly to companies. Last month the Trump administration directed securities regulators to study a longer reporting cycle for corporate results. Instead of every quarter, earnings would be disclosed every six months. Job creation and greater flexibility were touted as possible benefits. And Jay Clayton, the Trump-appointed chairman of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, wants to look at loosening restrictions on who’s allowed to trade shares in companies that have yet to go public.

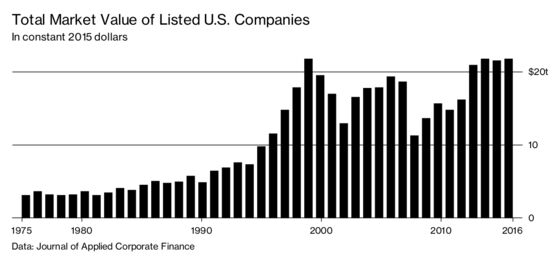

Either proposal can be framed as a way of making equity investments a little less boring and predictable. Yet it’s strange to think that a market that’s created more than $20 trillion in value in less than a decade should need more strategies to burnish its image. If companies are so sick of the stock market after a run like this, the mind reels to consider what they’ll think after the crash of 2019, or 2020, or 2025.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Pat Regnier at pregnier3@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.