Emerging-Market Rout Is Longest Since 2008 as Confidence Cracks

Emerging-Market Rout Is Longest Since 2008 as Confidence Cracks

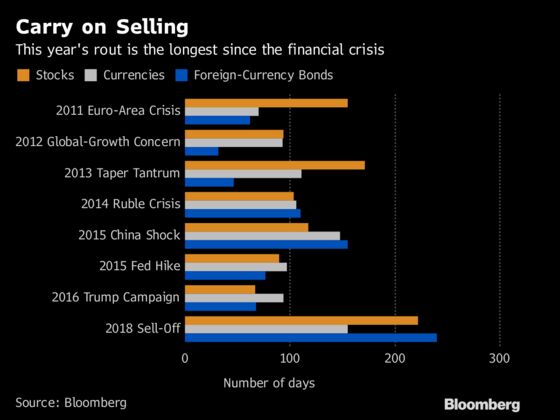

(Bloomberg) -- For stocks, it’s 222 days. For currencies, 155 days. For foreign-currency bonds, 240 days.

This year’s rout in emerging markets has lasted so long that it’s taken even the most ardent bears by surprise. Not one of the seven biggest sell-offs since the financial crisis -- including the so-called taper tantrum -- inflicted such pain for so long on the developing world.

The scope of the slide, as measured in the number of days from peak to trough, is pushing some strategists to say the slump is more than just a knee-jerk reaction to higher U.S. interest rates or the unfolding trade war. It’s become a full-fledged crisis of confidence for investors in developing nations.

While traders typically focus on how much they lose in terms of percentage change, that yields only a limited perspective on factors driving the markets -- or the potential for recovery. Short, intense sell-offs often lead to short, intense rebounds, lulling investors into a false sense of resilience. That’s what happened repeatedly in 2016 and 2017.

But looking at how long a decline lasts, not just how deep it is, can better expose fault lines. Lingering downtrends upend futures and options contracts, forcing traders to take losses. They also lock up investors’ collateral in the form of enhanced margin calls, leaving them little room to make other trading decisions.

A longer selloff also means the argument for buying the dip -- one frequently made by money managers earlier this year -- gives way to cautions over avoiding a falling knife. And that, in turn, can persuade money managers who treat emerging markets as one homogeneous group to sell weak and strong markets in tandem, no matter their specific fundamentals. It’s the very definition of contagion.

Emerging markets have been here before. From 2013 to 2015, they underperformed the developed world as a succession of shocks, including the Federal Reserve’s plan to dial down stimulus and China’s growth slowdown, limited any potential rebound.

The difference this time is the absence of even temporary resilience. It’s become a contest between the dollar and everything else denominated in the U.S. currency. That helps explain why there’s been simultaneous selling in a haven asset such as gold and riskier emerging-market assets.

"It’s true that the advice of investing gurus is that you make the most money when you take a contrarian view," said Tony Hann, a money manager at Blackfriars Asset Management Ltd. in London. "But you have to be really, really brave to buy in a market like this."

To contact the reporter on this story: Srinivasan Sivabalan in London at ssivabalan@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Dana El Baltaji at delbaltaji@bloomberg.net, ;Rita Nazareth at rnazareth@bloomberg.net, Alec D.B. McCabe, Brendan Walsh

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.