German Taste for Stocks May Sour on First Losses Since 2011

German Taste for Stocks Risks Souring on First Losses Since 2011

(Bloomberg) -- Germans, long known for exceptional caution with their cash, have been quietly shifting into stocks and funds from traditional savings accounts in recent years. Now that risks snapping back.

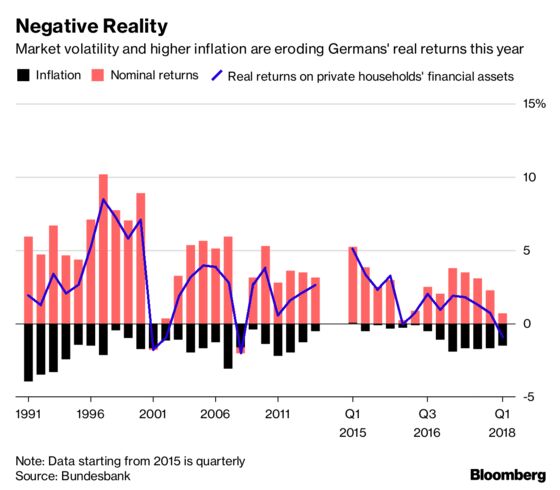

A combination of weaker markets and firmer consumer prices means inflation-adjusted returns so far this year are negative for the first time since 2011, according to Germany’s Bundesbank. With the European Central Bank expected to start raising interest rates in late 2019 -- which some analysts say could spur further market declines -- German households may opt to return to safety.

As in many other countries, Germany’s retail investors have historically made the mistake of buying shares when they were expensive and selling after they became cheap. These buy-high, sell-low missteps meant stocks were never fully integrated into wealth building, prompting a quick retreat when losses pile up.

“The problem is that Germans have always been very procyclical about investing,” said Franz-Josef Leven, deputy director of lobby group Deutsches Aktieninstitut (DAI). “I can imagine that many retail investors will switch back out of equities once interest rates go up. Not all of them, but a large part.”

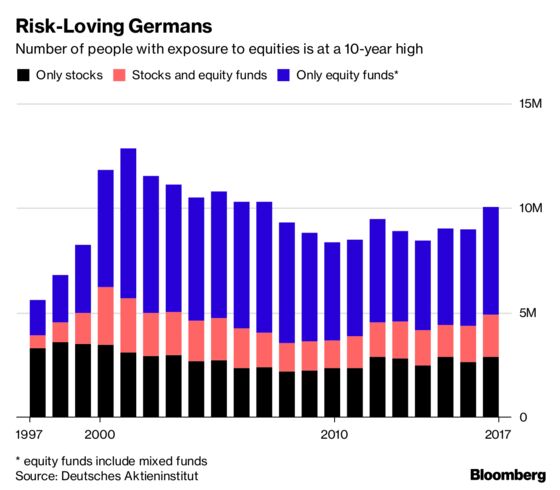

Bundesbank President Jens Weidmann highlighted the move toward stocks in a speech last week, saying his “rather conservative” compatriots put more than 26 percent of all their financial assets into equities and investment funds in 2017. That’s up from just 6 percent four years earlier.

One beneficiary is Frankfurt-based DekaBank, the asset manager of Germany’s savings banks. The company had record inflows last year, with retail clients pouring 12.3 billion euros ($14.4 billion) into funds, almost the same amount as institutional clients. CEO Michael Ruediger said this is a positive signal on Germans’ attitude toward investing in securities.

However, a downturn could reverse that trend, and investment losses could sap spending power among Germany’s rapidly growing ranks of retirees, who have little to fall back on. The country’s median net wealth per capita is at the lower end of its peers in Europe because of low investment holdings and limited home ownership.

Among people who do invest in equities, most earn an above-average income, have high education levels and are older than 50, according to DAI. Only about one in 10 people between the ages of 14 and 39 participate in the market.

German attitudes toward riskier assets are largely cultural -- neatly summed up in the word “Boersenscheu,” or “market shy” -- and inadequate financial education contributes to the prevailing disposition, according to DAI.

“In the U.S., families talk about 401Ks at the breakfast table, kids grow up hearing about it,” DAI’s Leven said in a telephone interview. “In Germany, you just don’t have that.”

Recent experiences underscore German risk aversion. The 2000 collapse of the Neuer Markt technology index saw many investors part with their equity and fund holdings, with sales of such assets largely outpacing purchases between 2003 and 2007. While the 2008 financial crisis saw slightly less procyclical behavior, the period between 2012 and 2014 saw average Germans miss out on good entry opportunities, according to DAI.

The question is how investment newcomers will react to declining equity markets this time around. After recent strong gains, Germany’s benchmark Dax index is down 3 percent so far this year.

Should households revert to savings accounts, German banks could find their business models under renewed pressure. Struggling with compressed interest margins because of the European Central Bank’s penalty on deposits, they’ve turned toward revenue streams such as fees for selling investment products.

Some younger investors like Daniel Schumann, a 35-year-old client-service manager from Stuttgart, are prepared to stick it out, at least as long as savings rates are low.

“Of course, a lot of capital was destroyed in no time,” said Schumann, who started to invest in stocks near last year’s peak fearing inflation may eat into his savings. But even if some stocks look worse than before the selloff, they are still better than a savings account, he added.

Not so when it comes to Germany’s political elite. Finance Minister Olaf Scholz revealed he’s an old-school investor. “I do it the way you should not do it,” he said during an interview with Handelsblatt newspaper. “My money is in a bank account, and I barely get any interest on it.”

To contact the reporters on this story: Jan-Patrick Barnert in Frankfurt at jbarnert3@bloomberg.net;Carolynn Look in Frankfurt at clook4@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Paul Gordon at pgordon6@bloomberg.net, Chris Reiter

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.