The Oil Trade Only for Those Ready to Brave the Wild Yuan

The Oil Trade Only for Those Ready to Brave the Wild Yuan

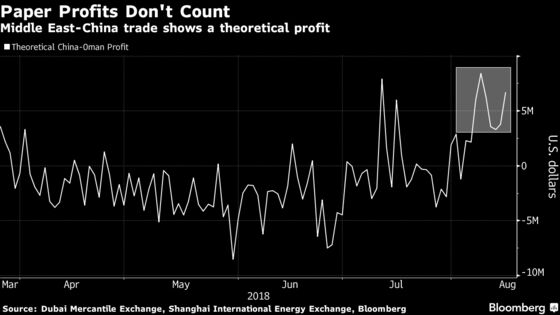

(Bloomberg) -- Wild swings in the yuan and punitive storage costs are making oil traders think twice about a bet on China’s fledgling crude futures that looks highly lucrative on paper.

Last week, taking into account freight costs, they could have theoretically bought a November-loading cargo of Middle East oil for delivery to a buyer of December futures in China at a profit of $3.35 a barrel, or $6.7 million for the whole shipment. That’s because Chinese futures, which started trading in March, fetched an unusually high premium versus oil from outside the region.

In practice, though, other risks associated with the Shanghai contract make the trade less of a slam-dunk. And they’re part of the reason why the yuan-denominated futures have a way to go before they become the global benchmark that Beijing wants to rival London’s Brent or New York’s West Texas Intermediate, which are both priced in dollars.

| On Paper at Least... | |

|---|---|

| $74.32/barrel | Chinese crude futures for December |

| $69.68/barrel | Oman crude for November |

| $4.64/barrel | Crude-prices gap |

| $1.29/barrel | Cost of freight |

| $3.35/barrel | Crude-prices gap, minus freight |

| 2,000,000 barrels | Typical supertanker cargo |

| $6.7 million | Theoretical cargo profit |

“There are a number of concerns for traders,” says Michal Meidan, an analyst at Energy Aspects. “The availability and cost of storing the crude in the designated storage tanks primarily.”

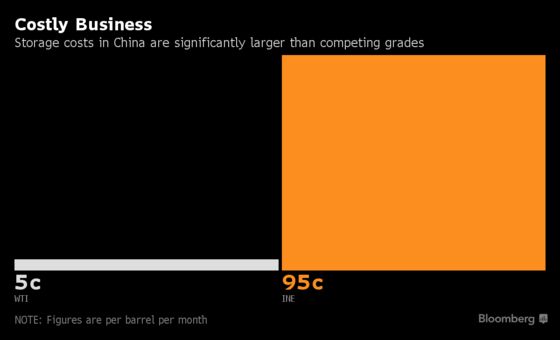

Storage Costs

Once the cargo arrives in China it has to be discharged into particular storage tanks before it’s picked up by the buyer. If it arrives before the delivery date, the seller will need to stump up the cost of storing it, and in China that’s prohibitively expensive.

The cost of holding barrels for delivery into the Shanghai International Energy Exchange works out at about 95 cents a barrel per month. That compares with as little as 5 cents at the Louisiana Offshore Oil Port this month, meaning that the profit could quickly be eroded by the cost of keeping supply in designated storage tanks.

Foreign Exchange

A trader buying dollar-denominated crude in the Middle East and selling it in yuan faces the risk of fluctuations in the exchange rate. If the dollar strengthens, the money the trader made from selling the cargo in yuan is worth less.

Traders can hedge their exposure, but recent swings in the yuan make it more perilous. The currency has been Asia’s worst performer since early May, dragged down more than 8 percent by the trade war between China and the U.S. and slowing domestic economic growth. Moves by the central bank to inject liquidity and support lending have put its monetary policy on a divergent course from America, also putting pressure on the yuan.

On Monday, the yuan jumped to the strongest in a week as the People’s Bank of China raised its daily reference rate on the back of a weakening dollar.

Timing Issues

The Chinese contract also has a shorter delivery window. While WTI can be delivered more than a month after the last trading day of the contract, those linked to the Chinese futures have just a week. As a result, traders would need any surge in prices to be sustained for a long period of time before additional barrels flow east east, Meidan said. A journey from Saudi Arabia to China takes about 21 days.

Liquidity

While daily volume in the yuan-denominated contract has increased about six-fold since its debut in late-March, almost all trading and open interest is focused in a single month, currently December.

For WTI and Brent, at least half of total volume and open interest is spread across contracts other than the most active one. The lack of liquidity in all but the most active contract in China will put off traders from trying to lock in arbitrage as it limits their options.

| More coverage of yuan crude futures: |

|---|

| Speculators rattle the futures as prices break from world Traders really dig the futures, but aren’t ready to commit Oil traders buy fast, sell fast in world’s newest futures market China seeks Goldilocks moment in Oil: How futures debuts compare We don’t need no speculation: China aims to skirt oil bubble |

Speculators

Analysis of aggregate open interest, volumes and trading hours indicates that the futures are being used mainly by short-term speculators. They’re holding contracts on average for an estimated 1.5 hours. That compares with 67 hours for London’s Brent crude and 49 hours for WTI. That represents a risk for anyone looking to hold a position for longer as they trade the arbitrage.

Fluctuations at the inventory points used to price the contract “created a temporarily tight physical market and incentivized speculative longs,” Citigroup Inc. analysts including Ed Morse wrote in a report earlier this month.

Currently there are only 100,000 barrels of warranted inventory, after 400,000 barrels were drawn at the Dalian warehouse in the week of July 30, according to the bank. There are 23.45 million barrels held in Cushing, the pricing point for WTI, according to data from the Energy Information Administration. And that’s near the lowest since 2014.

This is all not to say traders aren’t thinking about the trade. Of six traders surveyed by Bloomberg, four said they’re considering delivering Mideast crude into the December contract, which is now the most actively-traded and has the heaviest open interest. Two said the risks still remain too much.

Meanwhile, futures for December delivery fell 1.1 percent to 491.4 yuan a barrel on the Shanghai International Energy Exchange on Monday. Prices have lost about 6 percent over four sessions.

To contact Bloomberg News staff for this story: Alex Longley in London at alongley@bloomberg.net;Serene Cheong in Singapore at scheong20@bloomberg.net;Sharon Cho in Singapore at ccho28@bloomberg.net;Sarah Chen in Beijing at schen514@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Alexander Kwiatkowski at akwiatkowsk2@bloomberg.net, Pratish Narayanan

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.

With assistance from Editorial Board