Private Equity’s Biggest Mystery Has a Simple Answer

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Earlier this week, David Rubenstein, the co-chairman of private equity giant Carlyle Group Inc., said there are three great mysteries: What came before the Big Bang? Is there an afterlife? And why don’t private equity stocks trade higher?

The line got a laugh. But, despite the delivery, Rubenstein was asking something that he and others in his industry think is a serious question. And while it may be hard for Rubenstein and other PE titans to see — in part because they are at the heart of the problem — the answer is not all that mysterious.

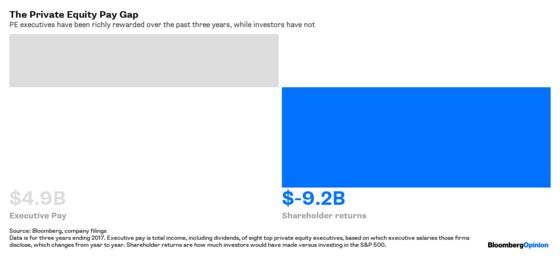

In 2015, eight executives at the four publicly traded private equity firms made a collective $1.9 billion. Shareholders in those same private equity firms lost a collective $13.7 billion. The next year, a similar group of executives made $1.1 billion, while shareholders got about half that, $573 million. Recently, private equity shareholders have done better. But it’s still hard to call the split equitable. Eight top executives made just under $1.9 billion last year, including a whopping $786 million for Blackstone Group CEO Stephen Schwarzman. The firms’ shareholders, all of them, made just $5 billion more than they would have if they had invested in the S&P 500 in the past year.

Public private equity firms have a unique balancing act. They have investors and shareholders. Both want the same thing — high returns. All companies have customers and owners, but the difference with private equity firms is that they can’t satisfy customers with, say, sleeker phones and shareholders with higher profits. On top of all that, they have to figure out how to compensate their employees to produce for both groups. It’s one too many conflicts of interest that has left shareholders feeling shortchanged and why the PE stocks do, and probably should, trade at middling valuations.

Rubenstein acknowledged that the conflict of interest is a big contributor to what he sees as PE firms’ weak stock prices. He said investors and shareholders want the firms to be compensated differently — investors want high incentive fees and low management fees, and shareholders want the opposite — and that the firms’ inability to bridge that gap has been the problem. But the real problem is the gap between what top PE executives make — Rubenstein took home $67 million in 2017 alone — and what shareholders make. That creates the distrust.

Solving that isn’t easy. A good deal of the income that PE executives make comes from the dividends on shares they own. It’s in no one’s best interest to force them to liquidate their sizable holdings. The next generation will have the same conflict. Jonathan Gray, Schwarzman’s heir apparent at Blackstone, made $275 million last year, in large part because of the dividends on his holdings of Blackstone shares. To companies that regularly exploit the difference between public and private valuations, the answer should be obvious. But if they don’t want to buy out their own shares, PE firms will have to live with the fact that they make for lousy public companies. An enigma of our age it is not.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Stephen Gandel is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering banking and equity markets. He was previously a deputy digital editor for Fortune and an economics blogger at Time. He has also covered finance and the housing market.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.