Why Libya’s Oil-Export Revival Stumbled, Once Again

The latest blow to Libya’s oil exports offers proof that its crude won’t flow reliably without a political solution.

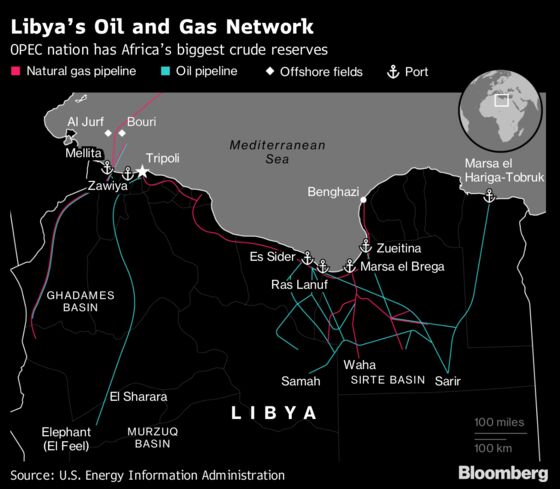

(Bloomberg) -- The latest blow to Libya’s oil exports offers proof that the country’s crude won’t flow reliably without a political solution to seven years of strife. Libya has struggled to revive its oil industry since a NATO-backed war in 2011, with militias clashing over energy facilities in the prized “oil crescent” along its central coast. Last month, forces loyal to Khalifa Haftar, a military leader with sway in eastern Libya, recaptured two key export terminals from rivals. He then transferred control of the ports and three others to an oil authority lacking international recognition. As a result, tanker loadings at the ports have ceased, depriving world markets of some 800,000 barrels a day. Libya’s instability complicates OPEC’s effort to pump more crude as well as United Nations-backed efforts to hold elections this year.

1. What caused oil exports to dwindle?

After reasserting control of the five ports in late June, Haftar put them under a self-declared National Oil Corp. based in the eastern city of Benghazi. That authority banned any loading of crude under contracts signed with its internationally recognized namesake in Tripoli in western Libya, deepening financial losses that the Tripoli NOC estimates at $920 million since fighting erupted in the coastal area earlier last month. (Libya continues to ship crude from ports run by the Tripoli-based NOC.) Haftar’s snubbing of the Tripoli NOC came as a surprise because, in 2016, his self-styled Libyan National Army seized the most important of the ports from another militia leader, Ibrahim Jadran, and handed control of them to the company. That transfer enabled Libya to restore oil output to 1 million barrels a day from lows of 250,000.

2. Why did Haftar turn away from the Tripoli government?

Haftar leads the main force opposing the UN-backed government of Fayez al-Sarraj in Tripoli. Backed by Russia, Egypt and the United Arab Emirates, he’s using control over oil ports to exert political pressure, according to officials and analysts including Claudia Gazzini, senior Libya analyst at the International Crisis Group. Haftar is surely aware that he can’t export oil independently, since international companies will only go through the NOC in Tripoli. Jadran, for instance, never succeeded in selling oil on his own, and in 2016, a tanker carrying crude from eastern Libya turned back after the UN blacklisted the shipment.

3. What does Haftar want?

Haftar’s forces say they never received any money or thanks from the Tripoli NOC for protecting oil facilities. The oil company’s chairman, Mustafa Sanalla, counters that crude revenue goes to the central bank and that he’s not responsible for how it gets distributed. Haftar, by keeping the eastern ports out of the Tripoli NOC’s control, maintains a grip on key arteries of Libya’s economy and can seek influence over the country’s few national institutions, including the central bank. The deterioration of the economy has stoked resentment in the east over a perceived misuse of funds and a view that too much wealth is concentrated in the west.

4. What impact do the port closures have on oil markets?

U.S. crude oil futures hit $75 a barrel on July 3 for the first time since 2014, capping two weeks of gains driven partly by the stoppages in Libya, holder of the largest crude reserves in Africa. Other factors included a U.S. push to curb Iranian sales and declining American inventories. The squeeze on Libya’s exports adds to pressure on Saudi Arabia, the biggest producer in the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, to boost output and curb prices that have drawn the ire of U.S. President Donald Trump. Libya currently pumps 527,000 barrels a day, and output will keep dropping day by day if the ports remain closed, Sanalla said in a July 9 statement on the Tripoli NOC’s Facebook page. A transfer of the terminals to his company’s control would be “an act of courage and nobility because no one wins in this battle, we all lose,” he said.

5. What does this mean for Libya’s economy?

The dinar, which is pegged at 1.34 per dollar, has tumbled since the latest port closures and was at 7 per dollar as of July 9. A frail currency spells higher prices in import-dependent Libya. A one-dinar bag of bread now contains three loaves instead of the usual four. The General Electricity Co. of Libya warns that if the halt in eastern oil exports persists, power outages in the east would extend to more than 12 hours a day. Motorists are stocking up on gasoline, with lines of vehicles snaking outside filling stations. Public anger is mounting.

6. How does this affect UN efforts to unify the country?

Rival political leaders, including Haftar, agreed at a May meeting in Paris to hold national elections and phase out parallel institutions under a UN-backed plan. The blueprint envisions a reunification of the country and its feuding administrations through votes for a new constitution, then for parliament and president. Mohammed El Dallas, spokesman for the Tripoli government, says that unless oil exports resume soon, elections can’t be held on time. Haftar has “damaged any image he tried to project as a potential unifier of Libya,” said Derek Brower, managing director of research at U.K.-based Petroleum Policy Intelligence. “All of this makes the idea of elections in Libya later this year look fanciful.”

7. Where does Libya go from here?

With its oil income curtailed, the country could hurtle toward more fighting and fragmentation. If a deal is reached soon and preparations for elections begin, however, the impact on oil markets and Libya’s economy could be mitigated. Two of the five crude-storage tanks at the port of Ras Lanuf were damaged in the latest fighting, reducing storage capacity there by 40 percent to 550,000 barrels, and this will hamper exports even after loadings can resume. More importantly, the ports dispute has eroded the trust Libya had rebuilt over the past two years with international oil partners. Any resumption in shipments will be dogged by “the underlying perception that the ‘oil crescent’ is again a highly contested area, subject to renewed attack,” Brower said.

The Reference Shelf

- QuickTake explainers on the Libyan conflict and the importance of two ports in Libya’s oil-export revival.

- An interview with Libya’s NOC chairman.

- Why Haftar makes fears of a divided Libya grow.

--With assistance from Saleh Sarrar and Samuel Dodge.

To contact the reporter on this story: Salma El Wardany in Cairo at selwardany@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Nayla Razzouk at nrazzouk2@bloomberg.net, Bruce Stanley

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.