Goldman Exit Shows Shortage of ETF Traders Who Make Market Tick

Goldman Exit Shows Shortage of ETF Traders Who Make Market Tick

(Bloomberg) -- A shortage of specialized traders who oversee ETF transactions on stock exchanges is threatening the boom in exchange-traded funds.

Issuers complain that it’s becoming increasingly difficult to hire lead market makers, or LMMs, who work to minimize the difference between the prices that buyers are willing to pay and sellers will accept. What’s the problem? With almost 2,000 funds in the U.S., the resources of these traders are wearing thin.

Goldman Sachs Group Inc. curbed its LMM business last year. And now even some of the high-frequency upstarts that took its place seem to be souring on the exchange-traded frenzy, data from the New York Stock Exchange show.

“Since the start of the year, no one wants to LMM,” said Mark Esposito, founder of Dallas-based Esposito Securities. “That weeds out some products from coming to market.” Esposito’s firm acts as an alternative source of startup money for new funds -- a role also traditionally played by these traders.

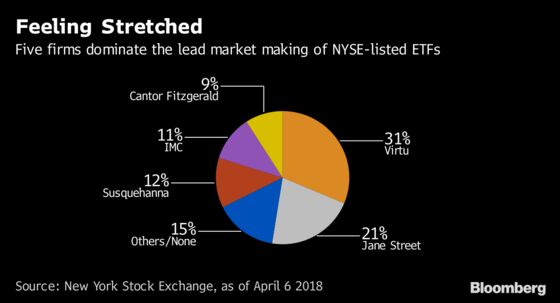

It’s a shift that’s been underway for a while. Goldman Sachs no longer supports any NYSE Arca-listed ETFs, down from more than 300 in 2016, exchange data shows. Instead, high frequency traders like Citadel Securities -- a new entrant -- Jane Street Group and the Dutch firm IMC BV have stepped up. But even they’re being more selective.

For example, Virtu Financial Inc., the largest lead market maker of ETFs, has trimmed the number of funds it works for following its acquisition of KCG Holdings Inc. last year.

“We reviewed and quantified the costs and benefits,” John DiBacco, who works on Virtu’s ETF block trading desk, wrote in an email. “In some cases, we determined that our resources were better focused elsewhere.” The firm added that it’s “wholly committed” to this business.

Glut Paradox

You wouldn’t know trouble’s afoot from the glut of ETFs coming to market. Issuers have started more than 75 this year -- 10 percent more than for the same period in 2017, data compiled by Bloomberg show. But the competition for services is fierce.

Michael Venuto of Toroso Investments witnessed it firsthand as he sought a lead trader for one of the first blockchain ETFs, which his firm sub-advises. Despite the hype about the theme “no one wanted to do it,” he said. “There’s very few left, and it’s a concern for our industry.”

But Venuto got lucky. Jane Street ultimately stepped up and the Amplify Transformational Data Sharing ETF, ticker BLOK, began trading in January.

Lacking Support

The problem is the newbies don’t always find a champion. The Breakwave Dry Bulk Shipping ETF, which started trading in March as BDRY, still doesn’t have a lead market maker, a person familiar with the matter said, asking not to be identified because the details are private. It trades freight futures, an asset class with which many ETF market makers are unfamiliar.

Without a lead market maker a fund’s bid-ask spread can balloon. In November, for example, the difference between offers to buy and sell an Eventshares tax-reform ETF -- which launched without a lead trader -- spiked to 116 basis points, Bloomberg closing-price data show. RBC Capital Markets was engaged to act as the LMM the following month, and the bid-ask spread of the recently rebranded fund has since averaged just six basis points.

“Only a handful of ETPs currently operate without a LMM, and in most cases the issuers of that ETP have developed a strong relationship with market making firms to provide consistent liquidity for their product,” said Doug Yones, NYSE’s head of exchange-traded products. “In the event an LMM no longer wants to be assigned to a particular ETP, we work with the issuer to find a new liquidity provider.”

Cry Tough

Even brand name issuers are having trouble lining up lead market makers. Three ETFs started by “Shark Tank” television personality Kevin O’Leary under the O’Shares brand operated without one for almost a year before Credit Suisse Group AG came on board last month, according to Kevin Beadles, director of capital markets and strategic development at the issuer. Cantor Fitzgerald had left the role in June 2017, according to the company.

Exchanges have used rebate programs to encourage lead market makers to stay, but some now want to pay these traders directly. The practice is the norm in Europe, but it’s banned in the U.S. The Financial Industry Regulatory Authority, however, sought comment on the prohibition, known as Rule 5250, late last year.

Issuers like Invesco Ltd., the fourth-largest issuer of ETFs, say paying market makers would enhance liquidity. But larger rivals Vanguard Group and State Street Corp. have expressed concern that this outlay will ultimately hit investors’ wallets. Others, instead, favor cutting the minimum amount of ETF shares needed to create or redeem a fund, a proposal that could ease market makers’ costs by reducing their inventory.

Regardless, most agree that something’s got to give.

“We need to address the problem, which is how do we maintain liquidity and incentivize market makers,” said Luke Oliver, head of U.S. ETF capital market at DWS, in which Deutsche Bank AG owns a majority stake. “The regulators are doing a great job by having these conversations.”

--With assistance from Annie Massa.

To contact the reporter on this story: Rachel Evans in New York at revans43@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Jeremy Herron at jherron8@bloomberg.net, Eric J. Weiner, Randall Jensen

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.