The No. 1 Lesson of the Lehman Collapse: QE Worked.

Doomsayers predicted that the Fed’s bond-buying spree would wreck the U.S. economy. Instead, it made the recovery possible.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Bloomberg Opinion marks the 10th anniversary of Lehman’s bankruptcy with a collection of columns from around the world. Read more.

Anyone attempting to understand the legacy of Lehman Brothers could start with two phrases that bookend the biggest bankruptcy in American history. The most famous is “too big to fail.” The most important is “quantitative easing.”

During the decade since Lehman collapsed, TBTF appeared in 2,241 articles on the Bloomberg terminal and became the title of a best-seller and a movie. QE shows up in more than twice that number of news articles. The lopsided difference helps explain lessons from Lehman’s demise.

Before Sept. 15, 2008, when the 158-year-old firm filed for Chapter 11 and thereby precipitated the deepest economic deterioration since the Second World War, few believed that the authorities would allow a behemoth like Lehman to trigger other insolvencies and shutter much of the global financial system. The stock market lost almost $10 trillion within a few months because too many people couldn’t imagine the contagion of toxic debt poisoning investors on several continents. When the fourth-largest investment bank after Goldman Sachs & Co., Morgan Stanley and Merrill Lynch & Co. did go under, credit evaporated and there was nothing preventing its larger peers from descending to a similar fate.

That’s when the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, acting as the agent for the U.S. Treasury, initiated its unprecedented and most controversial monetary policy during the final quarter of that year. Its quantitative easing program involving the monthly purchase of immense piles of bonds not only reversed the largest-ever plunge in U.S. gross domestic product, it also sowed the seeds of the ensuing 105-month expansion that has all the signs of becoming the longest in U.S. history. The immediate result was interest rates and inflation well below their combined level preceding every downturn since 1955. American companies, measured by their debt ratios, became the healthiest since such data was compiled by Bloomberg in 1995.

For the first time since it was founded in 1913, the Fed acquired all kinds of financial assets that were frozen after the Lehman default. It kept overnight borrowing costs at zero and allowed Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley to become commercial banks benefiting from such liquidity. This coincided with government interventions to prop up Bank of America and Citibank, insurer AIG, mortgage originators Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, General Motors, and Chrysler. And it finally discouraged Wall Street from taking ever-increasing risks with the money of shareholders and depositors.

QE was accompanied by “stress tests” for U.S. financial institutions in 2009 that were conceived by Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner, a former New York Fed president. They showed how much capital the 19 largest banks needed to survive another Lehman-style debacle.

The Fed ended QE in 2014, increased interest rates seven times since 2015 and last year began reducing its $4 trillion balance sheet as debt acquired during the bond-buying program matured. The Fed’s preferred measure of inflation, the Personal Consumption Expenditures Core Price Index, now sits at an annualized rate of 1.98 percent. At the same time, the big and small companies included in the Russell 3000 index saw their net debt to Ebitda ratio — or total debt minus cash divided by earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization — diminished to the lowest on record in 2015. It remains 2.2 percentage points below the Russell 3000 debt ratio of 2000.

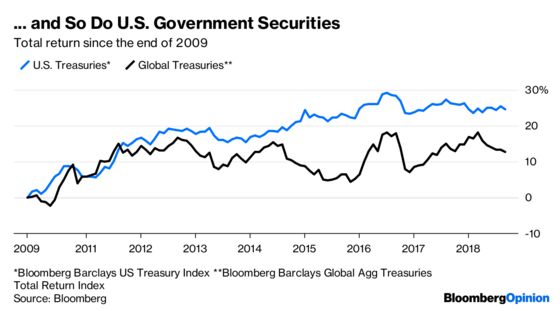

It’s doubtful that the economy’s robust health would have occurred without QE. But the academics, billionaires and politicians who denounced the policy as ruinous in a public letter with 23 signatures in 2010 still haven’t acknowledged QE’s role in the recovery and subsequent prosperity. The group, led by Stanford University Professor John Taylor, billionaire hedge fund manager Paul Singer and U.S. House Speaker John Boehner, predicted that the monetary stimulus would provoke runaway inflation, damage the dollar’s special role as the world’s reserve currency and send bond prices plummeting. They were wrong.

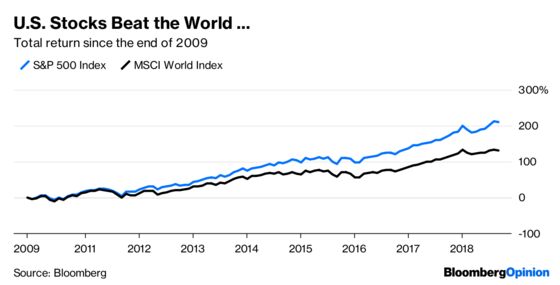

The recovery from the death of Lehman proved to be the most dynamic since 1980, with the rebound making the U.S. the only developed economy to attain record GDP by 2015, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. The dollar rallied 20 percent, the most of any developed economy’s currency during the past nine years.

After the crash of 1929, it took 25 years for the stock market to recover. The S&P 500, which lost 47 percent of its value in the bear market from September 2008 to March 2009, was at a record by 2013 and is up 327 percent from the recession low, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

Investors who anticipated a disaster for the bond market missed a total return (income plus appreciation) of more than $1.5 trillion from owning U.S. government securities during the period of quantitative easing. U.S. Treasuries produced a 24 percent total return, or 2.6 percent annually, since 2009. The rate of inflation, meanwhile, averaged 1.6 percent, which means that savers who kept their money in Pimco’s Total Return Fund easily beat inflation, with a total return of 37 percent, or 4 percent a year, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

Since the end of 2009, shares of U.S. financial firms gained 173 percent, 88 percentage points more than their global peers, as the second-best-performing industry among 10 groups led by consumer discretionary companies, including Amazon and Netflix. The value-at-risk of the portfolios of American banks, a measure of how speculative they had become by 2008, was significantly reduced by Fed-imposed regulations. JPMorgan’s VaR declined 90 percent while Bank of America’s was reduced 86 percent, Citigroup’s by 76 percent and Wells Fargo’s by 68 percent.

Ten years after its collapse, Lehman Brothers remains the world’s worst financial nightmare because it was too big and it failed. If it wasn’t for QE, we would still be living the bad dream.

(With assistance from Shin Pei)

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jonathan Landman at jlandman4@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Matthew A. Winkler is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He is the editor-in-chief emeritus of Bloomberg News.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.