Decade After Repos Hastened Lehman’s Fall, the Coast Isn’t Clear

The threat of cascading failures has now diminished after clearing banks stopped extending intraday credit to repo dealers.

(Bloomberg) -- Ten years after the collapse of Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. showed just how crucial short-term funding markets are to the financial system, no one is sounding the all-clear.

There’s no doubt that the Federal Reserve has slashed risk in the repurchase-agreement industry by prodding participants and working with global regulators to strengthen the banking sector. The events of 2008 showed why the efforts were needed: Panic in repos, which grease the wheels of debt trading and are a key tool for overnight financing, helped speed up the demise of Lehman and Bear Stearns Cos. in the span of six months.

The threat of cascading failures has now diminished after clearing banks stopped extending intraday credit to repo dealers, which at the height of the crisis left them exposed to as much as $1 trillion worth of funding. The market is also more transparent and smaller in scale.

Yet a key systemic risk still worries Fed and industry observers: The potential that a party may abruptly dump repo collateral in a so-called fire sale should another large firm go under. And there are new wrinkles to worry about -- the regulatory burdens on banks have reduced activity and left only one firm in the business of clearing deals.

“There have been a lot of things done that have added to the industry’s safety and soundness,” said Murray Pozmanter, head of clearing agency services at the Depository Trust & Clearing Corp., which settles the bulk of debt trading. “But there’s definitely still a lot to do and I’d say we are mid-journey.”

Repos’ Role

While most people are aware that the financial crisis stemmed from unbridled subprime-mortgage lending and the packaging of those loans into securities, fewer may recall the role played by secured funding -- meaning repos. When lenders perceived that Lehman might not repay repo loans or be able to post adequate collateral, they required more and higher-quality assets from the firm, crimping its ability to fund itself.

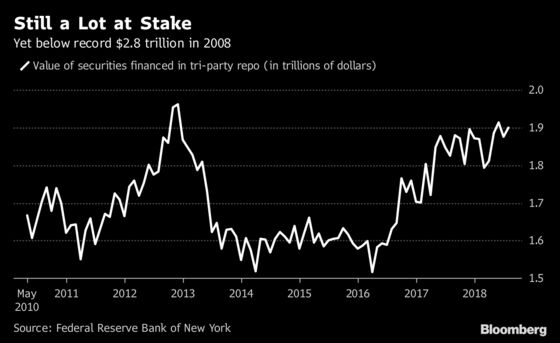

The landscape of the repo world has been transformed since the crisis. The sheer amount of collateral being financed in tri-party repo -- where a third party settles the deals and safeguards the debt -- has shrunk to $1.9 trillion from a record $2.8 trillion in 2008.

The contraction came as new global rules forced banks to hold more capital on their balance sheets and cut leverage, leaving them less room for repo transactions, and making the business more costly and less attractive.

Fire-Sale Threat

These changes haven’t extinguished the fire-sale risk. Efforts to move transactions onto central counterparty clearinghouses, which pool members’ capital to ensure losses at one firm don’t harm others, have proceeded at a glacial pace.

In 2008, the Fed had to step in -- by providing loan guarantees when Bear Stearns was absorbed by JPMorgan Chase & Co., and creating special facilities to prevent a cascade of repo collateral sales and to support its primary dealers.

“A lot has been resolved,” said Darrell Duffie, a finance professor at Stanford University who’s co-authored research on repos with Fed staffers. “That’s not to say that everything is perfect. There is still fire-sale risk that could be sparked if a dealer got into trouble. Those fire sales of collateral could bring down the prices of everything besides very safe securities, like Treasuries.”

Clearing Hurdle

The DTCC is spearheading central-clearing efforts and has brought some buy-side participants onto its platforms. Yet the biggest money funds in repo mostly don’t participate, in part due to regulatory mandates.

Pozmanter is still hopeful that more users will come aboard as the DTCC develops its clearing programs.

“There will definitely be more central clearing, that’s the track we are on,” he said. “We’ll have a broader swath of the market -- more participants -- accessing clearing.”

Regulators’ overhaul of the $3 trillion money-market fund industry -- a big source of demand for repo and other short-maturity debt instruments -- has helped bolster short-term markets, says Peter Yi at Northern Trust Asset Management, which manages $946 billion. That’s because in 2008 Lehman’s collapse -- which also brought down the $62.5 billion Reserve Primary Fund -- caused a run on money funds that only Treasury and the Fed programs stabilized.

“The industry better understands just how inter-connected these major broker-dealers are,” said Yi, head of short-term fixed income. “Investors and financial regulators now understand money markets were the proverbial canary in the coal mine during the crisis.”

Monopoly Power

Many claim the burden on major banks from mandates introduced after the financial crisis -- including Basel III and America’s Dodd-Frank regulations -- has reduced the appeal of dealing in repo as well as clearing and settlement in the industry.

Bank of New York Mellon Corp. is the only bank that remains active in settlement and clearing in the tri-party repo market after JPMorgan Chase & Co. left the business last year. This has unsettled some traders fretting that relying on a single clearing bank may mean trouble if something goes wrong.

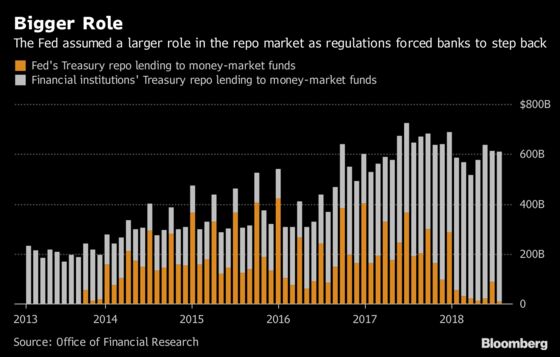

As banks have retrenched, the Fed has emerged as a major player in repo, which has given money funds other investment options to fill the void as dealers backed away.

The Fed got more involved in 2013 when it introduced an overnight reverse repo facility -- dubbed RRP. In this daily operation, the Fed offers counterparties such as money funds a fixed rate for parking cash with it overnight.

John Ryding, co-founder of RDQ Economics and the top U.S. economist at Bear Stearns when it was absorbed by JPMorgan, adds a new concern: the fact that Congressional measures have crimped the Fed’s ability to support individual firms in a future crisis.

In an extreme situation, “you need to have an unconstrained ability of the central bank to intervene,” said Ryding, who quickly brings to mind how on Friday, March 14, 2008, Bear’s repo desk told him access to funding was vanishing and set to be gone by Monday. On Sunday it was announced that JPMorgan had agreed to buy Bear with the Fed providing some financing.

“The financial system is a lot safer: There is more capital and it has a more forward-looking assessment of situations that could go on,” Ryding said. “But is the situation ideal now? No. And can we guarantee we won’t have another situation like that again? I don’t think we can.”

To contact the reporters on this story: Alexandra Harris in New York at aharris48@bloomberg.net;Liz Capo McCormick in New York at emccormick7@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Benjamin Purvis at bpurvis@bloomberg.net, Mark Tannenbaum, Jenny Paris

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.