Xi Has Lots at Stake as China Officials Point Fingers Over Virus

Xi Has Lots at Stake as China Officials Point Fingers Over Virus

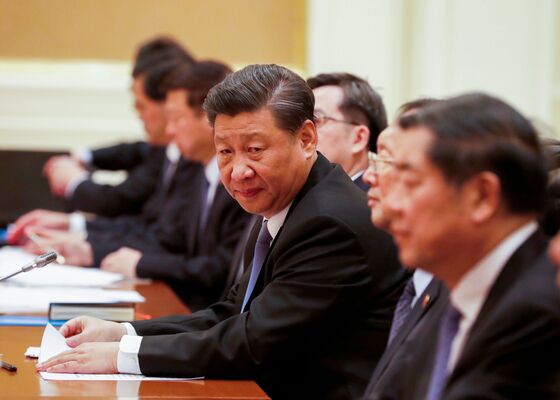

(Bloomberg) -- Since taking power Chinese President Xi Jinping has effectively made himself “chairman of everything.” The coronavirus scare is showing all the risks involved with that strategy.

Xi last week took direct control of the response to the outbreak, showing the high stakes in a crisis that has now killed 259 people in China and spurred panic across the globe. He’s overseen extreme measures, including quarantining more than 50 million people -- roughly equivalent to the population of Spain -- and rapidly building two new hospitals.

While lower-ranking Communist Party officials are starting to admit they were slow to contain the virus, senior leaders very quickly realized the enormous political stakes. Last Tuesday they issued a notice calling for cadres to think of the big picture, stay united and “resolutely uphold General Secretary Xi Jinping’s core position” in the party.

If all goes well, with a minimal hit to the world’s second-biggest economy, the benefits of Xi’s model of centralized control will be reinforced. But if the epidemic gets worse and the economic pain is deeper than expected, Xi “will deservedly take the blame,” said Scott Kennedy, an expert on China’s economy at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington.

“There’s no second lieutenant to blame this on,” he said. “And so as goes the virus, so goes Xi Jinping.”

Xi has become China’s most powerful leader since Mao Zedong in his eight years running the country, engineering constitutional changes to make himself the “core” of the Communist Party and scrapping presidential term limits. Along the way he’s also accumulated a number of enemies, particularly through a corruption purge that resulted in jail time for several senior party officials.

In China’s top-down system of government, much of the political intrigue takes place behind closed doors -- stability and control are cherished among top leaders. Worried that they may end up being scapegoats, local officials in the firing line are now publicly pointing fingers at each other.

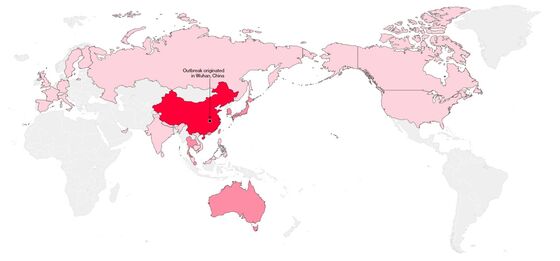

The mayor of Wuhan, the central Chinese city where the virus originated, said he had to wait for “authorization” before he could release information on the outbreak to the public. The chief epidemiologist of China’s Center for Disease Control and Prevention said the local government failed to recognize the problem from a scientific point of view, and probably had some “executive issues.”

“While no one person may be responsible for the fast spread of the coronavirus, it has resulted in a blame game within the bureaucratic system,” said Suisheng Zhao, executive director of the Center for China-U.S. Cooperation at the University of Denver’s Graduate School of International Studies. “The accelerated spread of the virus is also the result of political incompetence and a tightened control on ideology and information.”

In Xi’s China, lower-level officials must constantly weigh whether they are saying too much or too little. Since Jan. 24, some 33 local officials have been dismissed or scheduled for disciplinary review for allowing informal public gatherings, repeating misinformation via official channels, and failing to provide superiors with detailed updates, Eurasia Group, a New York-based consultancy, said in a note on Friday.

Xi himself has sought to get on top of the crisis, convening what state media dubbed an “unusual” meeting of the supreme Politburo Standing Committee to discuss the outbreak on Jan. 25, the first day of the Chinese New Year festivities. Similar emergency meetings occurred after the 2008 Sichuan earthquake, 2009 street violence in Xinjiang and a 2014 earthquake in the southern Yunnan province.

The worst may still be yet to come. Even before the outbreak, China’s economy was already slowing amid weak domestic demand, a crackdown on debt and the trade war with the Trump administration. The World Health Organization’s move to declare the coronavirus a “public health emergency of international concern” sparked fresh concern on Chinese social media about whether small and middle enterprises could survive as countries restricted travel to China.

In a containment scenario -- with a severe but short-lived impact -- the virus could take China’s first-quarter gross domestic product growth down to 4.5% year on year, according to Bloomberg Economics. That’s a drop from 6% in the final period of 2019 and the lowest since quarterly data that begins in 1992.

GLOBAL INSIGHT: Virus May Drag China GDP to 4.5%, Ripple Out

Chief economist Ren Zeping of China Evergrande Group, a Shenzhen-based developer, said Thursday that economic growth this year would slow to 5% due to a sharp drop in demand and production, a significant impact on investment, higher short-term unemployment and rising prices. The report by his team advised the government to provide subsidies for low-income people and “prevent social instability caused by the potential wave of unemployment.”

Disease outbreaks have a history of ending careers of party officials who dutifully sought to work their way up the ranks. In the wake of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome, which killed 800 people across Asia 17 years ago, China fired more than 100 officials, including the health minister and the mayor of Beijing, amid allegations that the health ministry suppressed information about the disease and local governments botched the response.

Heads have already started to roll this time around.

On Thursday, the health commission chief from Huanggang city in Hubei province -- which has seen more than 1,000 people confirmed with coronavirus, the most cases outside of Wuhan, -- was removed. Hours before the official announcement, local media circulated a video of her struggling to answer when grilled on figures related to the virus. Another 336 party officials were subsequently punished for incorrectly handling the outbreak, the city’s mayor told reporters on Saturday.

Earlier in the week, a health official in the coastal city of Tianjin was fired for being “derelict” in fighting the epidemic, the first dismissal over the virus.

Outrage on Chinese social media has shifted from focusing on Wuhan’s government to China’s CDC. Internet users said a paper by researchers from the agency issued Thursday revealed human-to-human transmission -- a significant escalation in the pandemic’s severity -- had been noticed in early January, earlier than reported.

“I’m out of anger, I don’t know what to say,” Wang Liming, a professor at Zhejiang University’s Life Sciences Institute, told his 480,000 followers on Weibo. “This is the first time I’ve seen clear evidence that human-to-human transmission of the new coronavirus has been deliberately withheld.”

His remarks were re-posted more than 60,000 times and liked more than 100,000 times before being taken down. The CDC said in a statement on Friday that the paper was based on “retrospective inference” of data from 425 cases, which had already been made public.

Other Communist Party members have acknowledged some mistakes. Ma Guoqiang, the Communist Party’s highest ranking member in Wuhan, where the outbreak originated, told state television that he was full of guilt and regret for not acting faster.

“Because we did not do our work well and failed to make a prompt decision, this resulted in the outbreak being exported domestically and internationally,” Ma said during a CCTV interview, noting that the government could have closed roads out of Wuhan on Jan. 12.

The crisis has also turned at least one previously little-known Communist Party member into a social media hero.

Zhang Wenhong, a director at the Shanghai Huashan Hospital’s infectious diseases department, received praise online after he pledged to send doctors who are party members to the front lines to relieve non-party members who had been working long shifts fighting the virus.

“I myself will make ward rounds at least one or two times every week,” Zhang told reporters at a briefing in Shanghai on Jan. 29. “I don’t care why you joined the party, or whether you agree to go to front line, you have to go now without bargaining.”

That kind of appeal to duty should help Xi as he seeks to rally the party into action. What he doesn’t need is people questioning the overall system, in which all roads lead directly to him at the top.

“Beijing wants to deflect as much of the criticism as they can to local authorities,” said Kennedy at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. “That helps strengthen the overall system’s legitimacy by saying the main challenge is in implementation. But the main real dominant structure of China’s political system really still emanates from Beijing.”

--With assistance from Karen Leigh.

To contact Bloomberg News staff for this story: Sharon Chen in Beijing at schen462@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Daniel Ten Kate at dtenkate@bloomberg.net, ;John Liu at jliu42@bloomberg.net, Andrew Davis

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.

With assistance from Bloomberg