Why Japan Is Dumping Water From Fukushima Into the Sea

Most nuclear power plants discharge small amounts of tritium and other radioactive material into rivers and oceans.

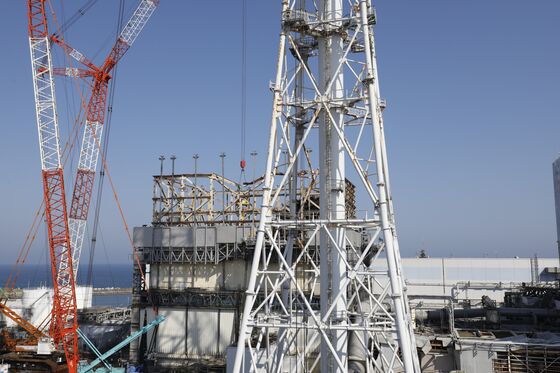

(Bloomberg) -- The Japanese utility giant Tepco is planning to release more than 1 million cubic meters of treated radioactive water -- enough to fill 500 Olympic-size swimming pools -- from the wrecked Fukushima Dai-Ichi nuclear power plant into the Pacific Ocean, part of its nearly $200 billion effort to clean up the worst atomic accident since Chernobyl. Storage tanks at the site are forecast to be full as early as mid-2022, and space for building more is scarce. Scary as it sounds, discharges are common practice in the industry and would likely meet global guidelines. That hasn’t assuaged angry locals or neighboring China and South Korea.

1. Where does the water come from?

A 2011 earthquake, the strongest ever recorded in Japan, and ensuing tsunami caused structural damage to Fukushima’s reactor buildings, about 220 kilometers (137 miles) north of Tokyo. While Tepco cycles in water to keep fuel and debris cool, roughly 140 cubic meters of water becomes contaminated daily, including groundwater and rain. The tainted water is pumped out and run through something called the Advanced Liquid Processing System, or ALPS, then stored in one of roughly 1,000 tanks at the site. The processing removes most of the radioactive elements except for tritium.

2. What is tritium?

A form of hydrogen that has two extra neutrons, making it weakly radioactive. It is naturally produced in the upper atmosphere and also is a common byproduct of nuclear power generation. It has various applications including in making nuclear weapons, in medicine as a biological tracer, and in producing such glow-in-the-dark items as exit signs and watch dials.

3. Is it dangerous?

It can be carcinogenic at high levels. While tritium’s beta particles (those emitted during radioactive decay) are too low-energy to penetrate the skin, they can build up in the body if inhaled or consumed (usually via tainted water). Yet according to the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission, a human would need to ingest billions of units of becquerels (a measure for radioactivity) before seeing any health effects. The Tepco tank with the highest concentration has 2.5 million becquerels per liter, according to data from Dec. 31. For comparison, a banana has 15 becquerels and 1 kilogram (2.2 pounds) of uranium has 25 million.

4. How is it handled?

Most nuclear power plants discharge small amounts of tritium and other radioactive material into rivers and oceans, according to David Hess, a policy analyst at the World Nuclear Association, an industry group. In the U.S., such “authorized releases” of so-called tritiated water are done “routinely and safely” and are fully disclosed, according to the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission. The International Commission on Radiological Protection’s recommendations, which form the basis for rules globally, limit liquid radioactive waste so that public radiation doses annually are less than 1 millisievert (a unit for measuring radiation exposure, abbreviated as mSv). For comparison, the World Nuclear Association says background radiation in the natural environment typically exposes people to an average 2.4 mSv a year, while a CT scan of the pelvis results in an effective dose of 10 mSv.

5. Why not build more tanks?

Tepco, or Tokyo Electric Power Company Holdings Inc., is essentially out of room on the facility grounds. It has already felled 500 square meters (5,400 square feet) of trees next to a bird sanctuary to make room for about 1,000 tanks. Japan could move toward more long-term storage on nearby land by investing in petroleum reserve tanks, the biggest of which can hold some 2.4 billion liters (20 million barrels) of liquid. It’s unlikely anyone will want to live in areas around the plant for a long time. But it would also require a political decision.

6. When will it be released, and how?

Tepco plans to begin releasing the water in early 2023 through a tunnel that will run about a kilometer offshore, company officials said during an August briefing. Before it’s released, the water will be diluted and reprocessed, the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry said earlier, and the government plans to strengthen its efforts to monitor radioactivity.

7. Who’s against a release? For it?

Fishing groups in Fukushima prefecture have been strongly opposed, fearing it could further taint the reputation of their catch and affect their livelihoods. Tepco in August pledged prompt compensation if anyone’s livelihood is damaged. (More than 20 countries still have import restrictions imposed after the disaster on some Japanese food products.) South Korea expressed “strong regret” over the planned release, saying it hadn’t been consulted. China has repeatedly urged Japan to revoke its “highly irresponsible unilateral decision,” while the U.S. has said the planned release was in line with global standards.

8. How’s the cleanup going otherwise?

The March 11, 2011, quake off Japan’s northeast coast and ensuing tsunami caused about 16,000 confirmed deaths and extensive damage, including the meltdowns at Fukushima. Since then, there’s been steady progress in the cleanup at the plant, which Tepco estimates will take 30 to 40 years more. In 2019 the utility sent a robot to touch melted fuel at the bottom of one of the reactors for the first time -- a necessary step toward developing a device to remove and dispose of it. An underground ice wall and drainage system was installed to reduce the amount of groundwater flowing into the wrecked reactors by more than half. The life of cleanup workers has improved as well. A thin surgical-style mask is all that’s needed to walk around most of the grounds, as opposed to a full body suit with a hard plastic mask covering the entire face. Radiation levels on the grounds have dropped, allowing for more work around the plant.

The Reference Shelf

- A parking lot for cleanup crews became a World Cup rugby training field.

- Japan’s environment ministry’s booklet on the health effects of radiation, and METI’s slide show on the cleanup effort and its website for treated water.

- The BBC looks at whether people are returning home.

- Fact sheets on tritium from the Health Physics Society from the U.S. nuclear regulator and from Canada’s.

- The World Health Organization answers FAQ on Fukushima.

- An inventory of radioactive waste disposals at sea from the International Atomic Energy Agency.

- Nobel laureate Henri Becquerel, the French physicist who discovered radioactivity.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.