Who Has the Most to Lose If China’s Trade Ambition Succeeds?

The exposed countries have a high dependence on exports and a substantial presence in the electronics, auto, and shipping sectors.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Ten months after President Donald Trump launched the first volley in a tariff war, the path to a future of free and fair trade looks increasingly narrow. On one side, rising protectionism in the U.S. threatens to undo decades of progress in dismantling barriers to commerce. On the other, China’s increasingly muscular industrial policy raises concerns that Beijing will spare no effort or expense to give national champions the edge over international rivals.

The origins of the current impasse go back to Nov. 10, 2001. On that date, at a meeting of the World Trade Organization in Doha, the club welcomed China as its 143rd member. Hailing the decision, then-President Jiang Zemin promised China would “strike a carefully thought-out balance between honoring its commitments and enjoying its rights.”

Behind the decision to admit China into the WTO was a U.S. high on post-Cold War hubris. The red menace had been consigned to the dustbin of history. Intellectual agreement on the benefits of free trade appeared unchallenged. China seemed committed, if not to a democratic transition, at least to a pro-market transition. WTO entry, it was hoped, would lock in Beijing’s reforms and bind China into the U.S.-dominated global system.

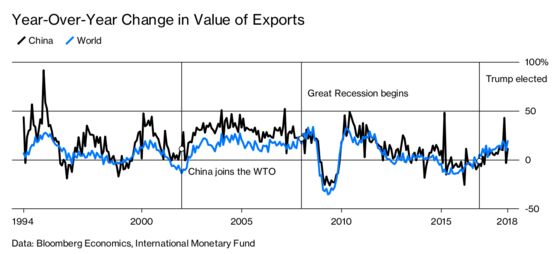

Early results were positive. In China soaring exports drove years of double-digit economic expansion, lifting hundreds of millions of people out of poverty. International companies tapped the country’s low-cost workforce to cut production costs and raise profitability. Global growth accelerated, rising to an average of 4.5 percent from 2002 to 2008, up from 3.5 percent from 1995 to 2001. Global trade growth picked up from an annual average of 6 percent in the seven years before China’s WTO entry to 14.7 percent from 2002 to the outbreak of the financial crisis in 2008.

But problems were brewing. (FIG. 1) China’s overseas sales boomed, yet its assembly lines remained dependent on components imported from Taiwan, South Korea, and Japan. Beijing policymakers worried that the country risked becoming stuck in the low-value-added end of the supply chain.

In the U.S. and Europe, blue-collar workers found themselves displaced by low-cost imports. One study estimated that from 1999 to 2011, as many as 2.4 million U.S. jobs were lost to China. With automation and a declining role for unions compounding the effect, wages for low- and middle-income earners stagnated.

Stateside, a populist backlash gathered force, fed by the wave of home foreclosures and layoffs unleashed by the financial crisis. The dynamics that propelled Trump into the White House were complex. But blue-collar anger about free trade and the impact of Chinese competition on U.S. jobs, as well as fear about China’s rise as a world power, were persistent themes in the campaign.

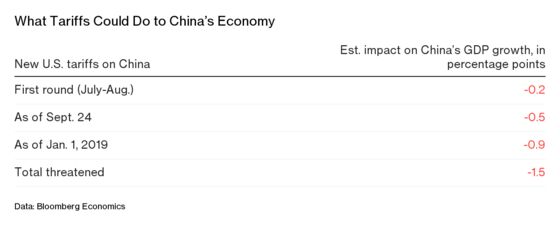

American presidential candidates bashing China was nothing new: Clinton, Bush, and Obama had done the same. With Trump, rhetoric became reality. As of late October 2018, the U.S. had imposed 25 percent tariffs on $50 billion in Chinese imports and 10 percent tariffs on an additional $200 billion. Duties on the $200 billion are set to rise to 25 percent at the start of 2019, and Trump has threatened to hike tariffs on the entirety of China’s $505 billion in sales to the U.S.

In China, the combination of weak global demand and local companies’ slow progress in bringing productivity to the levels in the U.S., Japan, and Europe dragged export growth to a standstill in the aftermath of the financial crisis. The country’s share of the global market for high-tech exports, which had been rising consistently from 2001 to 2010, plateaued.

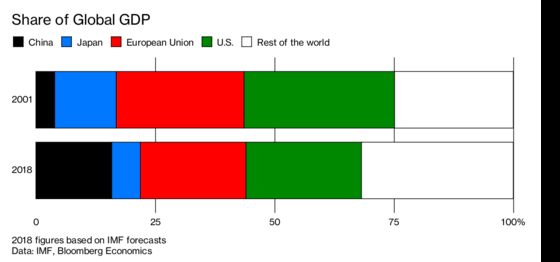

Not content with a role as the world’s factory, officials in Beijing began a series of initiatives aimed at making China the world’s robotics workshop, semiconductor foundry, and new-energy-vehicle production line. Those plans, culminating in the 2015 publication of the “Made in China 2025” program, fit squarely within an East Asian tradition of leveraging industrial policy to accelerate the manufacturing sector’s advance. Even so, they rang alarm bells for the U.S., Germany, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan—economies that dominate the sectors China targeted. Chinese competition had already displaced foreign companies in low-margin operations such as the manufacture of clothing, shoes, and toys. If the 2025 plan succeeded, remaining bastions of comparative advantage would face a fresh challenge. (FIG. 2)

Heading toward the 20-year mark, then, the factors that drove China’s WTO accession have swung into reverse. The U.S. accounts for a shrinking share of the global economy, while questions have arisen about the intellectual framework that underpinned support for free trade, with a new focus on the costs for the losers. Meanwhile, China’s 1990s commitment to pro-market reforms has segued into an activist industrial policy, testing the limits of WTO rules.

China 2025 and the Return of Industrial Policy

“Since the beginning of industrial civilization, it has been proven repeatedly by the rise and fall of world powers, that without strong manufacturing, there is no national prosperity.” Those words are drawn from the preamble of Made in China 2025. Back in 2015, when China’s State Council released the policy blueprint, it didn’t get a lot of attention outside of specialist circles. Three years later, with fears about China’s sudden rise spurring a protectionist backlash in the U.S., it has started to get a lot.

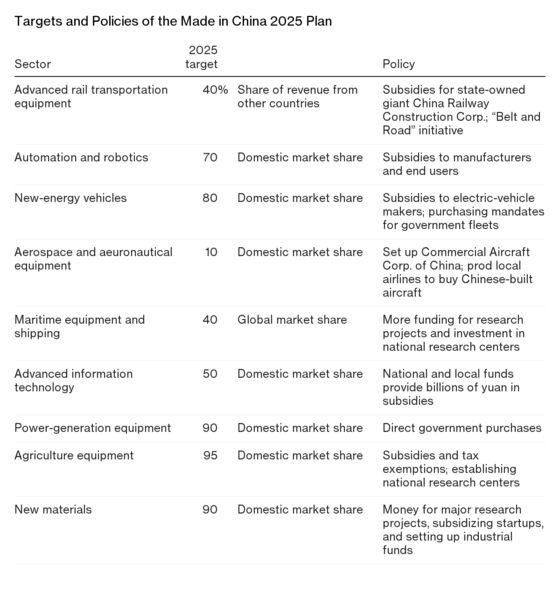

Implicit in the plan is the idea that the world is in the middle of a Fourth Industrial Revolution—a confluence of industrial robots, artificial intelligence, big data, and cloud computing remaking manufacturing. In the view of China’s industrial planners, domestic factories are “large but not yet strong.” By attempting to gain an edge in new technologies and integrating them into the manufacturing supply chain, China 2025 aims to solve that problem. (FIG. 3)

The plan identifies 10 key sectors: advanced information technology, digital control machine tools and robotics, airplanes, ocean equipment and shipping, rail-transportation equipment, new-energy automobiles, electric-power equipment, agricultural equipment, new materials, and biopharmaceuticals and medical equipment. The aim is to boost research and development and production capacity to displace foreign with domestic components. Add it up, and it’s the most ambitious attempted market grab the world has seen, with everyone from German automakers to Taiwan’s semiconductor fabs standing to lose out.

China’s industrial planning isn’t out of line with the development strategy of other manufacturing powerhouses. Japan’s rise to dominance in industries from automobiles to home electronics wouldn’t have happened without the strategic vision of the industrial planners at the Ministry of International Trade and Industry. And while governments in the U.S. and Europe have tended to be more hands-off, there’s public funding for science and technology, along with a vision—albeit often vague—for advancing competitiveness.

What stands out in the case of China’s 2025 plan are three factors:

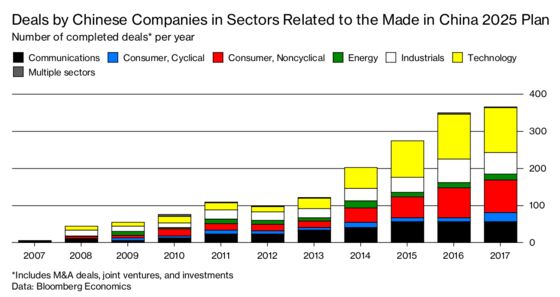

● Scale of government support. With investments from central and local government, state banks, and state enterprises, funding for China 2025 is considerable. The value of China’s mergers and acquisitions in the technology sector involving non-Chinese companies from 2015-17 was $35 billion, almost four times higher than in the previous three-year period. The Ministry of Industry and Information Technology has allocated $1.5 billion to support target industries. In comparison, Germany has allocated $230 million to its “Industry 4.0” program. (FIG. 4)

● Testing the limits of fair competition. A report released in March by the U.S. Trade Representative ran through a litany of charges, adding up to the accusation that China isn’t playing fair. The 215-page document concludes that China is deploying a well-financed strategy to “displace” foreign companies and “undermine the global trading system.”

● China’s size and politics. Taiwan, South Korea, and even Japan could transform themselves into industrial powerhouses without testing the global balance of power. China, with its population of 1.4 billion, has to climb only a little further up the development ladder to overtake the U.S. as the world’s biggest economy. As a single-party state and a geopolitical rival to the U.S., China will challenge the global order as it becomes the economic leader.

Winners and Losers From China 2025

As the rapid growth of China and its East Asian neighbors demonstrates, industrial policy can be brutally effective. But there’s no shortage of failed projects and wasted investment to demonstrate that it can also go awry. Subsidies for infant industries can kick-start development. They also can lead to overcapacity, low profits, and limited resources for needed investments. That’s what happened in China’s solar industry and may be happening again in robotics.

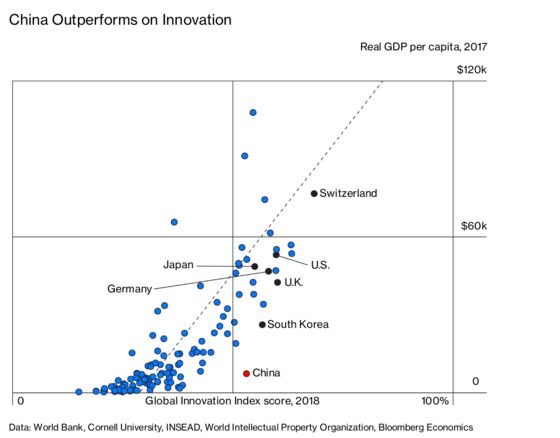

At a macro level, China’s attempt to catch up with global technology leaders continues to show steady progress. Spending on research and development rose to 2.1 percent of gross domestic product in 2016, up from 0.9 percent in 2000. In dollar terms, only the U.S. spends more. The country is climbing in global rankings. In 2010, China ranked 43rd in the Global Innovation Index, a joint effort of Cornell University, INSEAD, and the World Intellectual Property Organization. In 2018 it had risen to 17th, making it the highest-ranked middle-income country. (FIG. 5)

At a sector level, prospects sharply differ across the 10 areas targeted as part of the 2025 plan. In some, such as rail-transportation equipment, China already dominates at home and is making inroads in the global market. In robotics and others, the gap between domestic and global companies remains wide, and progress toward closing it has been halting—China’s unit purchases of industrial robots hit a record in 2017, but domestic suppliers saw their share fall.

Three data-driven approaches provide a guide to where Chinese companies are catching up with global leaders and where they’re not:

● Patent applications. In most of the sectors targeted in China 2025, the country has increased its share of patent applications over the past decade, with progress in next-generation information technology especially rapid.

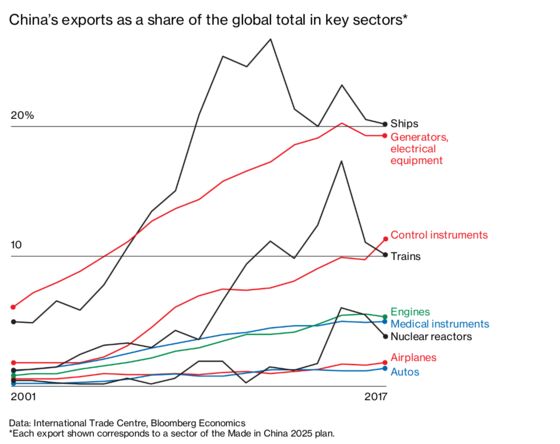

● Trade. In shipping, power equipment, and rail equipment, China has picked up significant global market share. In engines, medical equipment, and nuclear reactors, it’s gained a little. Elsewhere, progress is more limited. (FIG. 6)

● Revenue. In sales of rail equipment and new-energy vehicles, Chinese manufacturers have already overtaken global leaders; they’re catching up in maritime equipment, power generation, information technology, and biopharma and medical products; for the remaining sectors, the gap is wide and not being closed.

Viewed together, these three gauges suggest concerns about China’s activist industrial policy may be overblown. Even so, it’s worth asking who has the most to lose if the country succeeds in its ambitions. Based on an analysis of data compiled by the International Trade Center—an agency of the WTO—Germany, South Korea, and Taiwan stand out as the most exposed. All have a combination of high dependence on exports and a substantial presence in the sectors Made in China 2025 is targeting. German autos, South Korean electronics, autos, and shipping, and Taiwanese electronics all face a competitive threat from China’s push.

Japan, the U.K., France, Italy, and Spain are somewhat less exposed. They have a lower dependence on exports and a smaller presence in the sectors China has set its sights on. Automobiles in Spain and Japan, engines in the U.K., airplanes in France, and electronics in Japan are among the most vulnerable industries.

The U.S. has the least to fear, because of its low dependence on exports and relatively limited presence in vulnerable sectors. One exception is airplanes, but so far China’s plans to incubate domestic rivals haven’t gotten off the ground. Ironically, Trump’s America-first trade policy may end up being a bigger help to China’s other competitors than to the U.S.

Assessing the Costs of a Trade War

Relations between Trump and President Xi Jinping started nicely enough. At an April 2017 summit meeting the two leaders enjoyed chocolate cake, promised a 100-day plan to tackle trade imbalances, and made positive noises about a joint approach to North Korea.

The bonhomie lasted longer than the dessert, but not much. Underscoring the change in the mood, in May 2017 Trump appointed Robert Lighthizer as chief trade negotiator. In the 1990s, Lighthizer—then a lawyer in private practice—opposed China’s entry into the WTO.

China’s attempts at conciliation, including opening the door to foreign ownership in banking and autos, promising greater protections for intellectual property, and even pledging extra purchases of U.S. beef, poultry, and liquefied natural gas to reduce the trade deficit, proved ineffective. In July 2018 the Trump administration imposed 25 percent tariffs on $34 billion in Chinese exports, swiftly following that with an additional $16 billion. As of late October, the U.S. had imposed tariffs on $250 billion in Chinese imports—almost half of the total. And Trump has threatened higher tariffs, applied to an even wider range of goods.

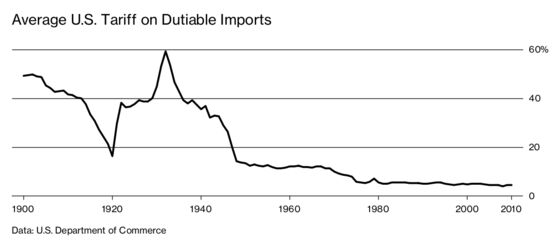

It would take much more to bring tariffs back to levels triggered by the infamous Smoot-Hawley tariff act, which deepened the Great Depression. (FIG. 7) Yet the tariffs are already high enough to dent China’s growth and blunt the impact of Trump’s tax cuts in the U.S.

What happens to the global economy if the trade war escalates? There are two main channels through which it could hamper growth.

● Real economy. Higher import costs drive up inflation, squeezing the purchasing power of households and dragging consumption down. Businesses respond to weaker demand by lowering investment spending, exacerbating the downturn. In the medium term, productivity growth slows as fewer of the benefits of trade openness are captured.

● Financial markets. The trade war threatens to be a significant drag on corporate earnings. A sustained slump in equity prices would deal a blow to household wealth and confidence—curbing consumer spending. It would also raise the cost of capital and dent business confidence, damping investment.

Based on this thinking, we map out four possible scenarios:

SCENARIO 1

$250 billion and done

The current U.S. tariffs on $250 billion in Chinese imports are expected to slow China’s GDP growth by 0.5 percentage point in the year ahead. The impact will be greater if the U.S. follows through on its threat to raise tariffs on the latest $200 billion tranche to 25 percent from 10 percent, effective Jan. 1.

Because of the substantial role imported components play in China’s exports—accounting for about a third of the total—the pain of tariffs will be spread around, with South Korea, Taiwan, and Japan also taking a hit.

Chinese tariffs cover $110 billion in U.S. goods, and on average are set at a lower rate than U.S. tariffs on Chinese goods. The impact on GDP will likely be masked by the effects of the Trump administration’s $1.5 trillion tax cut. (FIG. 8)

SCENARIO 2

$250 billion plus market slump

To gauge the effects of a drop in U.S. equity prices on the world economy, we applied a global vector autoregression model that captures the historical economic relationships among 33 countries.

The negative impact of a 10 percent decline in equity prices on U.S. GDP growth could be as much as 0.4 percentage point in 2019, with world output growth slowing by 0.2 percentage point.

China would probably emerge relatively unscathed from a U.S. equity slump. The correlation between U.S. and Chinese stock prices is low, reflecting the limited openness of Chinese financial markets to global investors. Equity markets also play a limited role in China’s financial system.

SCENARIO 3

10% on everything

What if the trade war really escalates? NiGEM, a model of the global economy developed by the London-based National Institute of Economic and Social Research, provides a means to estimate the impact on growth.

Assume the Trump administration puts a 10 percent tariff on all imports to the U.S. and the rest of the world responds in kind. By 2020, U.S. GDP would be 0.7 percent lower than if there were no change in tariffs. Output for China and for the world as a whole would be lower by 0.3 percent.

The smaller impact on China and the world relative to the U.S. reflects the fact that, in this scenario, trade between China and non-U.S. nations is not affected.

SCENARIO 4

10% on everything plus market slump

Combining the impact of a slump in equity prices and a drag on the real economy, by 2020 U.S. output would be 1.5 percent lower than if no tariffs were imposed. Global output would be lower by 0.7 percent.

For China, the equity impact would again be negligible, reflecting the limited role of stocks as a source of capital or store of wealth in its economy and the low correlation between U.S. and Chinese stock prices.

To be sure, the U.S. is not currently threatening 10 percent tariffs on all imports, but rather directing its energies at China. A trade war could unfold in myriad ways not captured here; financial market reactions are tough to predict, and a stimulus response from Beijing or Washington could offset any drag in growth.

Even so, the costs of an escalating confrontation could run high, and not just for China and the U.S. In an ideal world, such an awareness should motivate nations to work together to dial down tensions and find new rules of the road for the global trading system, where commitments and rights for all participants are better in balance. —With Justin Jimenez, Qian Wan, Jamie Murray, and Yuki Masujima

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Cristina Lindblad at mlindblad1@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.