Wall Street Now Hawks Research Like a Budget Airline Sells Seats

Some of the biggest banks have priced written research cheaply in order to lure clients to pricier premium services.

(Bloomberg) -- If you’ve ever flown on a discount airline—paying extra for everything from seat selection to a bottle of water—you have a pretty good idea how financial firms sell research these days.

You want to talk to the analyst? Hear from an economist? Attend an industry conference? Meet a corporate executive? Order up a customized report? There’s likely to be a fee for each—unless you’ve opted for the premium all-in-one fare.

That’s because under European rules introduced last year to promote transparency and investor protection, banks are required to attach a price to a service that for decades had been a fringe benefit for trading clients. But after 18 months, pricing remains something of a mystery for both buyers and sellers.

“It’s difficult to try and work out what the right value is,” said Nick Burchett, head of U.K. equities at London-based Cavendish Asset Management, which oversees 1.8 billion pounds ($2.2 billion). “It’s not like going to buy a book.”

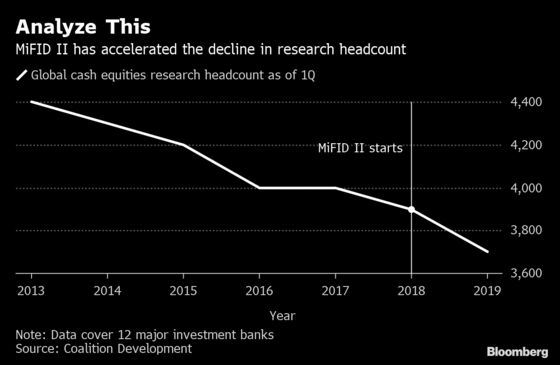

Few sectors have been as damaged in the finance industry’s recent history as research: from the regulators’ crackdown to being made increasingly obsolete by passive investing and artificial intelligence, analysts are fighting ever harder for a smaller piece of a shrinking pie. The 12 top investment banks employed about 3,700 people in cash equities research globally as of the first quarter, down 14 percent from 4,300 five years ago, according to Coalition Development Ltd. data.

And now that clients have to earmark cash, research spending has tumbled further, with the biggest firms gaining an even greater edge and boutiques sharpening their niche. For the vast middle, it’s a struggle to hang on. The latest illustration came this month when BNP Paribas SA decided to outsource most of its Asian equity research to Morningstar Inc.

“You’re starting to see the buy side consolidate their research providers,” Benjamin Quinlan, chief executive officer of financial-services consultancy Quinlan & Associates in Hong Kong. “If you’re having to shell out and cough up money for research out of your own pocket, you’re not going to go to a ninth or 10th-ranked analyst that BNP has to offer you. You want to go with the top one, two or three.”

A survey of 27 banks, brokers, fund managers and specialized research shops by Bloomberg shows that the ante is generally $10,000—about how much JPMorgan Chase & Co., Deutsche Bank AG and Citigroup Inc. charge for their written research.

Some critics, like the European Association of Independent Research Providers, have called that predatory pricing. The organization says one report alone from an independent shop costs $2,000 on average.

Pricing models span from all-you-can-eat packages to tiered subscriptions that can be customized to a client’s needs and size—a sign that even research remains largely a relationship business. The average revenue per client ranges from $1,600 to $1 million annually, according to a survey of research providers by U.S. consulting firm Integrity Research Associates LLC.

Some of the biggest banks have priced written research cheaply in order to lure clients to pricier premium services—a “perfectly legitimate” business model, says Sanford Bragg, principal at Integrity Research, which helps the buy side find research.

For written analysis, Morgan Stanley charges $25,000 for 10 users, while Goldman Sachs Group Inc. has offered the same price for four logins. At Bank of America Corp., it’s $30,000 for five users with an additional point system for querying analysts and attending events. Buying 50 points costs $20,000. A one-on-one meeting with corporate executives is $150 per attendee to arrange. These prices are according to fund managers who asked not to be identified because the agreements are confidential.

JPMorgan, Citi, Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley and Bank of America declined to comment. Deutsche Bank and the European Securities and Markets Authority didn’t respond to emails seeking comment.

The new rules mandated by the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive, or MiFID II, have generated complaints about fairness from every corner. Detractors say MiFID II favors big banks over smaller brokerages and independent research analysts; bigger asset managers over smaller ones; U.S. firms over European ones, and large-cap stocks over smaller ones. In short, Goliath over David.

Read more: French Regulator Calls for Study on MiFID II Impact

Big banks have a few advantages. One, their coverage is more comprehensive. Two, because of their diverse revenue streams, they can afford to make less money off research. Among top-tier clients, 60 percent of their external research and advisory budget in Europe goes to global investment banks, according to data provider Greenwich Associates.

“Some of our competitors as a result have increased the cross-subsidization of their research departments from their banking,” said Colin McGranahan, head of research at Sanford C. Bernstein in New York. “What it’s causing in some instances is sort of a return to a situation we try to correct two decades ago where banking is now paying for a much larger portion of the research department and is exerting more influence over how the research department acts.”

In the second year under Mifid II, the market is starting to stabilize. After slashing equity research budgets by 19 percent last year, large European institutions are planning just another 6 percent cut in 2019, with the average budget at $8.3 million, Greenwich data show.

Meantime, the U.K. Financial Conduct Authority has said that it’s examining whether prices that are too cheap still constitute inducement; it’s due to issue a report on the topic in the third quarter. The agency declined to comment.

Amid the complaints, there’s a bright side for some fund managers.

“We actually discovered it’s quite nice to have fewer phone calls, fewer emails,” says Thomas Brown, a London-based fund manager at Miton Group, which oversees 4.6 billion pounds. “We get more time to actually do our own work.”

--With assistance from Nishant Kumar, Suzy Waite and Cathy Chan.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Blaise Robinson at brobinson58@bloomberg.net, James Hertling

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.