Volcker Recalls Another Time the Fed Was in the President’s Crosshairs

Trump’s repeated criticism of Fed’s monetary policy seems extraordinary, but he’s not the first president to oppose raising rates.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Donald Trump’s repeated public criticism of the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy seems extraordinary, but he isn’t the first president to oppose raising rates. Paul Volcker, 91, has had firsthand experience with this, both in Lyndon Johnson’s Treasury Department and as Fed chairman during the Reagan administration, as he recalls in Keeping at It: The Quest for Sound Money and Good Government (Oct. 30, PublicAffairs), written with Bloomberg Markets Editor Christine Harper. Volcker, who was Fed chairman from 1979 to 1987, is credited with ending an era of double-digit inflation by pushing short-term rates as high as 20 percent.

Later in the fall of 1965, Treasury Secretary Henry Fowler became deeply concerned about a warning he had received from Fed Chairman William McChesney Martin. The Fed planned to raise its discount rate, the rate the Fed charges banks for short-term loans, with the presumed effect of raising all market rates. Martin’s clear aim was to forestall inflationary pressures as Vietnam War spending rose in an already fully employed economy. A spirited internal debate developed. The Council of Economic Advisers and the Bureau of the Budget lined up with Fowler in pleading for delay. Privately, I was sympathetic to Martin’s argument and hoped to persuade the secretary into a compromise: perhaps a quarter-percentage-point increase instead of the planned half-point.

The unfortunate result for me was the creation of a four-man ad hoc committee to examine the issue. The composition was odd. Although I was the Treasury’s representative, I was eager to compromise. Dan Brill, the Fed’s research chief, was strongly opposed to any rate hike despite his boss’s view. So were, in varying degrees, representatives from the CEA and the Bureau of the Budget (now the Office of Management and Budget). Predictably, we concluded that the decision could wait until January so it could be coordinated with the new budget.

Martin persisted. A Quadriad (1) meeting of “principals only” with President Lyndon Johnson was scheduled for Oct. 6. Secretary Fowler brought me along. He laid out the issue. The president recoiled at the idea of raising interest rates. It would, he said with an arm outstretched and fingers clenched, “amount to squeezing blood from the American working man in the interest of Wall Street.”

Chairman Martin was unyielding. As he saw it, the restraint was needed and it was his responsibility. “Bill,” the president finally said, “I have to have my gall bladder taken out tomorrow. You won’t do this while I’m in the hospital, will you?”

“No, Mr. President, we’ll wait until you get out.”

And so it was done. In early December 1965, soon after I left the Treasury, the Fed did act, voting to raise the discount rate to 4.5 percent from 4 percent. Johnson, down in Texas, released a disappointed statement. Martin was called down to the “Ranch” to be given a mental, and by some reports a physical, trip to the proverbial woodshed. (2)

I don’t know the full story, but it was a lesson for me. Over time two things did become clear. The Fed was slow to take further restrictive actions as Vietnam expenditures and the economy heated up. The president overruled his economic advisers’ private pleas for a tax increase. My guess is that he understood that a tax vote in Congress would simply become a referendum on the unpopular Vietnam War—a referendum he would be bound to lose.

An Awkward Meeting

As this memoir makes clear, the Federal Reserve must have and always will have contacts with the administration in power. Some coordination in international affairs is imperative given the overlapping responsibilities with respect to exchange rates and regulation. Sweeping use of “emergency” and “implied” authority requires consultation if for no other reason than to reinforce the effectiveness of the action. But that needs to take place in the context of the Federal Reserve’s independence to set monetary policy.

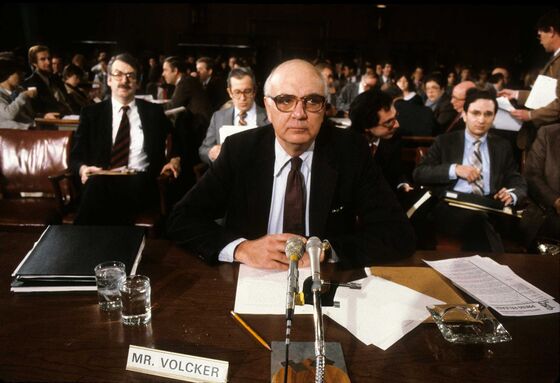

That was challenged only once in my direct experience, in the summer of 1984. I was summoned to a meeting with President Reagan at the White House. Strangely, it didn’t take place in the Oval Office, but in the more informal library. As I arrived, the president, sitting there with Chief of Staff Jim Baker, seemed a bit uncomfortable. He didn’t say a word. Instead, Baker delivered a message: “The president is ordering you not to raise interest rates before the election.”

I was stunned. Not only was the president clearly overstepping his authority by giving an order to the Fed, but also it was disconcerting because I wasn’t planning tighter monetary policy at the time. In the aftermath of Continental Illinois’s collapse (3), market interest rates had risen and I thought the Federal Open Market Committee might need to calm the market by easing a bit.

What to say? What to do?

I walked out without saying a word.

I later surmised that the library location had been chosen because, unlike the Oval Office, it probably lacked a taping system. The meeting would go unrecorded. If I repeated the incident to the other members of the Federal Reserve Board or to the FOMC—or to [Wisconsin] Senator William Proxmire, as I had promised to do if such a situation arose—the story would have inevitably leaked, to nobody’s benefit. How could I explain that I was ordered not to do something that at the time I had no intention of doing?

As I considered the incident later, I thought that it was not precisely the right time for a short lecture on the constitutional authority of the Congress to oversee the Federal Reserve and the deliberate insulation of the Fed from direction by the executive branch.

The president’s silence, his apparent discomfort, and the meeting locale made me quite sure the White House would keep quiet. It was a matter to be kept between me and Catherine Mallardi, the longtime faithful assistant to Federal Reserve chairmen. But it was a striking reminder about the pressure that politics can exert on the Fed as elections approach.

1. The Quadriad had been established in the Kennedy years as an informal but influential grouping of the four top economics agency heads: Treasury, Budget, the CEA, and the Fed.

2. By some accounts the encounter got physical, with the 6-foot-4 president backing up the shorter Fed chief against a wall.

3. The failure of Continental Illinois National Bank & Trust Co. in 1984, the largest in U.S. history at the time, gave birth to the term “too big to fail.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Cristina Lindblad at mlindblad1@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.