Visa Headaches Discourage Foreign Applicants to U.S. B-Schools

Anti-immigrant rhetoric in the U.S. is prompting prospective students to think twice about applying to U.S. business schools.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Last year Surbhi Verma quit her investment banking job in Mumbai, moved to Silicon Valley, and started a master’s in finance program at Santa Clara University’s Leavey School of Business. She thought the degree would help her land a prestigious job with a good salary in the U.S.

That isn’t proving to be the case. “The first question recruiters ask you, without asking for your credentials, is, ‘Do you need visa sponsorship?’ ” says Verma. “And the moment you say ‘yes,’ you can immediately see that they’re not interested. It’s demoralizing.”

It’s long been hard for foreign talent like Verma to get work visas in the U.S. But since Donald Trump took office last year, his administration has made it even harder, and the anti-immigrant rhetoric coming from the president and his supporters is prompting prospective students to think twice about applying to U.S. business schools. That’s put B-schools across the country, from MIT Sloan School of Management, No. 4 on Bloomberg Businessweek’s 2018 ranking, to SCU-Leavey, not ranked, in a tough spot.

Edwin Koc, research director at the National Association of Colleges and Employers (NACE), says that beyond communicating openly with international students, “there really isn’t much schools can do. The administration’s tone has made students fearful.”

Many B-schools are warning prospective students about the difficulty of landing a job in the U.S. and suggesting employment alternatives when they arrive on campus. Columbia Business School, ranked No. 7, brings an immigration attorney to campus each semester to address what Michael De Lucia, director of the school’s International & MS Career Management Office, calls “rumors and uncertainty.” In addition to the career workshops the school has long organized for international students, Columbia this spring started bringing Canadian officials to its New York City campus to explain the country’s express entry program for skilled workers.

Susan Brennan, an assistant dean who oversees the career development office at Sloan, says work visas have become “a burning issue at the most senior level” of many schools. She’s been meeting with dozens of executives and recruiters to learn whether the government’s policies are dissuading them from hiring foreign Sloan graduates. “There’s a sense it may take longer, but they’re staying the course,” she says of employers. Only 47 percent of U.S. companies plan or are willing to hire international graduates of B-schools this year, down from 55 percent last year, according to a survey of nearly 1,100 employers released in June by the Graduate Management Admission Council, which administers business school entrance exams.

Nicole Hu, a master of finance student at Sloan, expected to return to Hong Kong after graduation because of stricter immigration policies. Then, in August, a major bank in New York offered her a job, which she plans to start in February. Hu is making backup plans, because once her student visa runs out, her employer will need to apply for a temporary work visa in the government’s lottery system. “It’s whether your stars align,” says Hu.

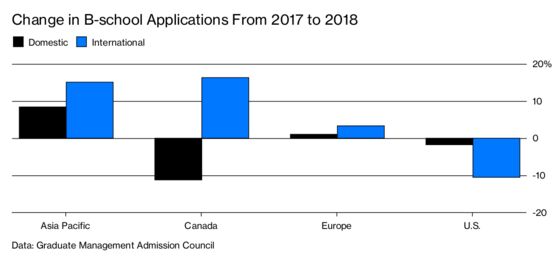

International applications dropped about 11 percent in 2018 at 400 U.S. graduate business programs, according to a GMAC survey released in October. Among prospective students who prefer full-time MBA programs and plan to apply internationally, 47 percent prefer the U.S. as a study destination, down from 56 percent in 2016, according to a separate GMAC survey of almost 9,500 students.

Impeding international talent is bad for B-schools’ economics because many depend on foreign students, who often pay full tuition. Schools that lack the global brand of a Harvard Business School, No. 3, for example, are “somewhat more exposed,” says Sangeet Chowfla, president and CEO of the GMAC. “They’re having more difficulty getting quality applications, forcing them to make some uncomfortable choices about not filling the classroom or lowering their admission standards.” B-school deans also worry the perception that the U.S. doesn’t want foreign students will reduce classroom diversity, Chowfla says, making the schools less appealing to some students and recruiters.

Some B-schools, particularly those outside urban areas, are experiencing significant declines in foreign enrollment, says Caryn Beck-Dudley, Leavey’s dean and board chair of the accrediting group AACSB International. One reason: Prospective students are concerned about their personal safety, says Chowfla, a troubling trend reflected in GMAC surveys. Leavey is considering sending staffers overseas to reassure foreign students.

Safety concerns aren’t misplaced, says Dana Bucin, an immigration lawyer who’s spoken to hundreds of students at Columbia and other schools. “The environment for all immigrants, including and especially foreign students, has gotten much tougher,” she says. Not because the laws have changed, but because the Trump administration is enforcing old laws more harshly and creating new policies, Bucin says. The government is increasing processing times and adding requests for more documentation, she adds.

In an email, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services spokesman Michael Bars said: “USCIS will continue adjudicating all petitions, applications and requests fairly, efficiently, and effectively on a case-by-case basis to determine if they meet all standards required under applicable law, policies, and regulations.”

In August, more than 50 executives from such U.S. companies as Apple, Johnson & Johnson, and JPMorgan Chase signed a letter to the Department of Homeland Security from the advocacy group Business Roundtable, arguing recent USCIS policies are “unfair and discourage talented and highly skilled individuals from pursuing career opportunities in the United States.” This harms American competitiveness, it said.

Making it harder for foreigners to work in the U.S. doesn’t help American workers, says Koc, NACE’s research director. “If the best talent is international, employers are going to find a way to access that talent,” he says. If new hires end up working out of a company’s office in Toronto instead of Pittsburgh, for example, the U.S. economy “loses all the multiplier effects,” from support positions to taxes paid.

Verma is considering relocating from Silicon Valley to another country that’s more welcoming or returning to India. To work temporarily in the U.S., she would need a job offer within three months after she graduates in December. Her employer would then need to apply for one of a limited number of temporary work visas, among other steps. Verma doesn’t like the uncertainty. “The whole environment is draining,” she says. She’s telling Indian friends who are considering U.S. B-schools to rethink their plans. “It’s a huge financial investment to come and study in the U.S.,” she says. “If you don’t find a good return on investment and have to go back jobless, it doesn’t seem like a good option.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Dimitra Kessenides at dkessenides1@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.