Bond Market Lessons From Australia’s Test of Yield Curve Control

Bond Returns Have Vanished in Australia With Yield Curve Control

(Bloomberg) -- As the coronavirus pandemic brought economic growth to an abrupt halt this year, the central banks of Australia and New Zealand responded quickly and decisively with aggressive bond-buying programs.

But there have been very different outcomes for bond holders after policy makers in Sydney chose to focus on yield curve control while their counterparts in Wellington stuck with more familiar quantitative easing.

In Australia, which geared its purchases to pinning down the three-year yield, bonds lost 0.2% in the quarter just ended, making them the third-worst in developed markets, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. New Zealand’s bonds returned 2.2% over the same period, putting them among the better performers, after the central bank set a target for the amount of debt it would buy.

“The bond returns reflect clearly the difference in approaches by central banks,” said Hamish Pepper, a fixed-income and currency strategist at Harbour Asset Management Ltd. in Wellington. “People believe there should be a premium for New Zealand bonds relative to Australia’s because of the RBNZ’s outright purchases compared with the RBA’s YCC.”

While the economies of Australia and New Zealand aren’t identical, they have much in common, providing a unique insight for investors trying to gauge the potential impact on bond returns as policy makers from the U.S. to Europe consider the merits of going from quantitative easing to yield curve control.

Both countries have cut benchmark interest rates to 0.25% and their currencies tend to move in tandem. They each depend on commodity exports while also leaning heavily on the tourism and education sectors. And relative to the rest of the world, the two nations have largely succeeded in containing the coronavirus.

Yet as investors have found in Japan, home to the biggest experiment in yield curve control since World War II, eking out returns under this kind of monetary regime gets very tough.

Left Behind

Ayako Sera, a market strategist at Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Bank Ltd. in Tokyo, points to the obvious challenge for bold holders: Yield curve control pins yields.

“When other markets rally, bonds under YCC can be left underperforming,” she said.

The rally in kiwi bonds over the past quarter has seen notable gains in five-, seven- and 15-year maturities, as investors take comfort from the Reserve Bank of New Zealand purchasing across the yield curve.

Aussie bonds have slumped, with a large drag coming from a selloff in 12-year tenors, as the central bank concentrated its buying in shorter maturities to fix three-year bond yields near its 0.25% target.

Cost Effective

For the Reserve Bank of Australia though, yield curve control has been a cost-effective way to stimulate the economy by capping interest rates for borrowing terms up to several years.

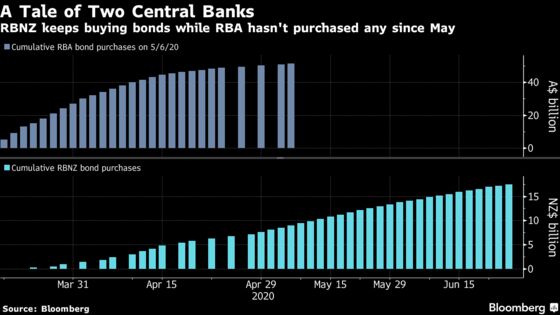

Since setting its target in late March and launching into a flurry of purchases, the RBA hasn’t had to buy bonds for eight weeks. This benefit won’t have gone unnoticed by other central banks.

By contrast, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand pledged to scoop up NZ$60 billion ($38.7 billion) of bonds over 12 months and it hasn’t stopped buying since.

While the pace of purchases has eased from a peak in April, the RBNZ has indicated it may increase the size of the program. Some economists predict it could go as high as NZ$120 billion.

Just over half of the economists surveyed by Bloomberg from May 29-June 3 expect that the Federal Reserve will eventually turn to yield curve control.

While the next meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee is at the end of July, economists see September as the most likely time for any announcement on YCC, and two- or five-year maturities the probable target.

Investors appear to agree. The five-year Treasury yield dropped to a record low this week as money continued to pour into trades that assume short- to medium-term yields will stay low while yields on longer-dated bonds rise more.

Experience Down Under supports this approach.

Australia’s three- to 10-year yield curve has steepened about 40 basis points from a low in early March. New Zealand’s two- to 10-year yield curve has gone up about 30 basis points over the same period.

To be sure, the picture for bond holders may change in unexpected ways as the coronavirus crisis drags on and the two central banks contend with a rising tide of debt issuance from their governments.

The next opportunity for investors to hear an update from the RBA on yield curve control comes on July 7, when the policy board meets.

Their counterparts at the RBNZ gather a month later on Aug. 12 and are expected to provide an outlook for bond purchases.

“Yield curve control is going to get more airplay globally,” said Prashant Newnaha, a senior strategist at TD Securities in Singapore. “The Fed has been canvassed as the next central bank to entertain it.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.