U.S. Pain Can Be Emerging Markets’ Gain

Emerging markets are reliving their 2015 nightmare. A U.S. stock correction may be just the thing to rouse them.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Emerging markets are reliving their 2015 nightmare. A U.S. stock correction may be just the thing to rouse them.

Three years ago, developing countries’ stocks lost almost a quarter of their market value in the months from October to January. China’s foreign reserves slid as Beijing scrambled to stem a flood of capital outflows. Meanwhile, a hurriedly implemented circuit breaker, intended to halt mainland A-shares’ decline, turned out to be futile.

Now we are seeing a similar slump, albeit at a slower place. U.S. stocks, by comparison, have hardly seen a correction.

The S&P 500 Index has benefited from an “America First” mentality. The Federal Reserve is on track to hike rates four times this year, followed by two more in 2019. The $3.5 trillion of easy money unleashed by the U.S. central bank’s quantitative-easing program, a good chunk of which went toward higher yields in emerging markets, are now poised to come home. With all signs pointing higher, stocks seemed like an obvious place to put your money.

So this pause in the S&P’s record bull run — even if it’s brief — could be just the thing to slow developing nations’ outflows.

Some pockets of the emerging-market sell-off are looking increasingly irrational, anyway.

After Bloomberg Businessweek reported last week that China used a tiny chip to infiltrate U.S. servers, a new twist to the escalating trade war, investors dumped Chinese hardware makers — so much so that it seems they no longer expect China Inc. to generate any overseas sales at all. PC maker Lenovo Group Ltd., which gets 17 percent of its profit from the U.S., has lost almost a quarter of its value. Similarly, surveillance-camera maker Hangzhou Hikvision Digital Technology Co. tumbled 17 percent over the same period, despite negligible sales in the U.S.

In the event of a “total trade war” — in which the U.S. would stop buying all Chinese-branded electronics, and Beijing would reciprocate — American brands stand to lose $43 billion a year, 2.7 times China’s loss, according to CLSA. If the sell-off deepens, it should really be on U.S. soil.

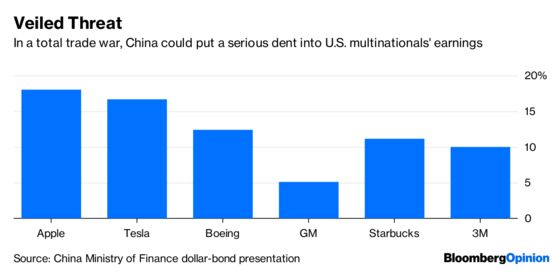

During this week’s roadshow for its dollar-bond sale, China’s Ministry of Finance painstakingly pointed out that many U.S. multinationals — including Apple Inc., Tesla Inc., Starbucks Corp. and Boeing Co. — get a sizable chunk of their sales from the mainland. That amounts to a thinly veiled threat: Beijing has the leverage to cause a serious correction in U.S. stocks.

As I argued recently, valuation premium between the U.S. and emerging markets has reached a historical peak. Developing economies may not be playing catch-up now — because liquidity there is still tight — but it’s high time for U.S. stocks to come back down to earth.

And that’s not necessarily a bad thing. Stubbornly persistent outperformance of one market could spell trouble as the world’s most prominent central bank continues to mop easy money off the floor. We are now in a zero-sum game.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Rachel Rosenthal at rrosenthal21@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Shuli Ren is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Asian markets. She previously wrote on markets for Barron's, following a career as an investment banker, and is a CFA charterholder.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.