The U.S. Failed in Venezuela Last Time. It’s a Different World Now

Venezuela’s economy is in a tailspin, prompting millions to flee to neighboring states.

(Bloomberg) -- When the U.S. rushed to endorse a military coup against Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez in 2002, it ended up with egg on its face. The self-styled leader of a “Bolivarian” revolution was back in office within three days -- and more anti-American than ever.

The decision by Washington to recognize National Assembly leader Juan Guaido as the nation’s legitimate president could see a repeat, if Chavez-heir Nicolas Maduro should cling onto power. But it takes place in a very different geopolitical climate, one where failure risks global repercussions.

Venezuela’s economy is in a tailspin, prompting millions to flee to neighboring states that have backed the U.S. in refusing to recognize Maduro’s 2018 re-election, widely seen as fraudulent. The coup against Chavez was condemned by many Latin American governments as anti-democratic. Now it’s the military that’s keeping an authoritarian Maduro in power, in the face of much stronger domestic and regional opposition.

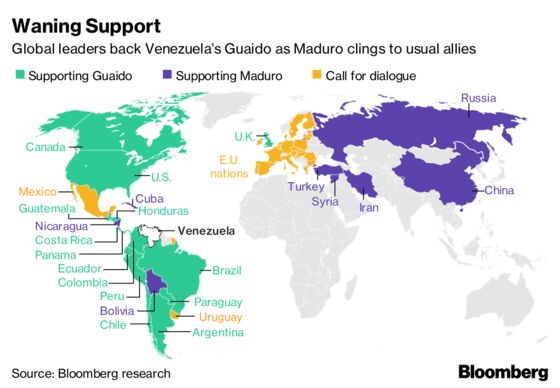

Yet the current stand-off is also freighted with great-power rivalry -- between China, Russia and the U.S. -- that barely existed in Venezuela 16 years ago. That’s providing Maduro with a reservoir of international support in standing up to Washington that Chavez didn’t enjoy. It also creates risks for the country’s long-term stability, should these powerful external players dig in to protect their loans, investments and political interests.

A wider ideological split on whether to prioritize democracy or sovereignty has also been added to traditional left-right divisions over what to do about Venezuela. That has joined Turkey to Maduro’s camp of authoritarian backers, determined to avoid new precedents for pro-democracy uprisings that could one day threaten their own positions.

“We’re worried this is turning into a geopolitical contest,” said Alejandro Martínez Ubieda, an opposition figure who was secretary of the Venezuelan delegation to an inter-parliamentary congress in St. Petersburg in 2017.

On Thursday, National Security Adviser John Bolton tapped those concerns when he explained to reporters why the U.S. abruptly decided to intervene in a country that was previously seen as posing a limited threat to American interests. “The fact is Venezuela is in our hemisphere,” Bolton said.

U.S. Senator Marco Rubio -- who lobbied the White House for action -- listed four reasons for why President Donald Trump cares about Venezuela in a Tweet on Friday, including an alleged offer by Maduro to host a Russian naval and air base “in our hemisphere.”

It isn’t clear how far the U.S. administration is willing to go to remove Maduro. A Latin American official at the United Nations in New York said his government has been in contact with Washington over the issue and understands the plan is to exert gradual pressure to trigger the Venezuelan leader’s resignation rather than instant regime change.

Russia and China combined to block any formal statement on Venezuela at a UN Security Council meeting Saturday. U.S. Secretary of State Michael Pompeo told the UN that Guaido should be recognized as rightful leader, rapping Beijing and Moscow for "propping up a failed regime in the hopes of recovering billions of dollars in ill-considered investments and assistance made over the years.” Russia’s UN ambassador accused the U.S. of trying to engineer a coup in Caracas, while China said it was not a matter for the UN at all.

Russia and China have made significant geopolitical bets on Venezuela over the last decade, filling the investment and security vacuum left by Washington’s estrangement from the government in Caracas.

Pompeo was gone on Saturday by the time Venezuelan Foreign Minister Jorge Arreaza spoke at the UN and outlined U.S. interventions in the region dating back to the Monroe Doctrine of 1823. Arreaza accused the U.S. of trying to "trigger a civil war in Venezuela."

Payback for what both China and Russia see as U.S. interference in their own spheres of influence has also been a factor in the decision to meddle in Washington’s backyard. Beijing resents U.S. activities in the Asia-Pacific region.

Involvement is driven by high levels of money borrowed by Venezuela and, with it, a geopolitical quid pro quo, according to a Latin American diplomat who asked not to be identified, citing political sensitivities. “The China-Russia presence, which is contributing to an unstable situation in South America, is totally unacceptable,” the diplomat said.

China has invested more than $62 billion in Venezuela, mostly through loans, since 2007. Last year, it imported 3.6 percent of its oil supply from the country, down from just over 5 percent in 2017. On Friday, the foreign ministry again warned against any external “threats of force or interference” in the country’s in the internal affairs.

Still, a change of leadership that incurred losses for China would be affordable for its $12 trillion economy -- and unlikely, according to Xue Li, director of international strategy at the state-run Chinese Academy of Social Sciences Institute of World Economics and Politics.

“Venezuela is still in flux and if Guaido comes to power he would still need Chinese investment, which is an irreplaceable source,” Li said. “In the long run, the current situation won’t impact China’s interest in this country.”

Russia, with far fewer resources to spare, may be more at risk. It is also involved in developing oil fields that account for just under half of Venezuela’s reserves, based on data from official news agency TASS.

State-run oil major Rosneft PJSC has stakes as high as 40 percent in five Venezuelan fields with collective reserves estimated at 20.5 billion metric tons. Rosneft is also owed about $3 billion worth of payments in oil. In a December visit to Moscow, Maduro signed up for further $5.5 billion worth of Russian investments.

Asked about potential losses on Govorit Moskva radio on Friday, Rosneft spokesman Mikhail Leontyev said: “What losses? Nothing has happened there. Everything that’s going on there has been happening for the last five years, every day. There’s a pretty big mess in Venezuela.”

Since 2006, Russia has also been Venezuela’s top military supplier, providing helicopters, combat aircraft and anti-aircraft missile systems. In a possible signal of Moscow’s strategic intent in the region, Deputy Prime Minister Yury Borisov said on Friday that Russia may reopen a former aircraft servicing center in Cuba.

Russia believes Maduro will be safe so long as he has the support of the military, which he appears to have, according to a foreign policy official in Moscow who asked not to be named because he isn’t authorized to speak to media.

But the official also said much would depend on how far the U.S. is willing to go to remove Maduro. Some have expressed concern that in such a scenario, Russia would be unable to respond effectively.

“Venezuela has probably the ugliest model of economy you can find,” said Alexander Chichin, Latin America specialist at the Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration in Moscow. “Russia won’t be able to help Maduro, more than just by showing moral and diplomatic support. It is too far from Russia.”

Building Ties

In a lengthy Facebook post, State Duma legislator Yevgeny Primakov went further. In its hurry to secure energy contracts and wine and dine Venezuela’s questionable elite, he said, Russia failed to invest in the “soft power” projects that could have built bonds with an obviously suffering population. That would have ensured that Russian interests would survive any change of power, he said.

As for Turkey, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan began to build a relationship with Maduro only in 2016, after a failed coup attempt in which Turkish officials have routinely alleged U.S. complicity. Investment and contracts followed.

Tons of Venezuelan gold -- strip-mined under grim conditions in Maduro’s dash to raise cash -- are being shipped to Turkey for refinement and processing. U.S. officials say some of the gold may be making its way to Iran, in violation of U.S. sanctions on the Islamic Republic. That would echo a previous Turkish gold-for-Iran scheme that has been successfully prosecuted in U.S. courts. Tehran has also backed Maduro against Washington’s recent move.

Last year, trade between Turkey and Venezuela reached $1.1 billion compared with just over $800 million in the previous five years combined, according to data from the official Turkish Statistical Institute. Maduro has warned the U.S. not to interfere with this growing bilateral trade.

“Venezuela’s history is very similar to ours, there were many coups in that country too,” said Serkan Bayram, a lawmaker from Turkey’s ruling Justice and Development party and chairman of the Turkey-Venezuela Inter-Parliamentary Friendship Group. He attacked Trump’s decision to recognize Guaido. “He’s saying I’ve appointed this person. Are you appointing a governor or an ambassador? No one can accept this.”

--With assistance from Dandan Li, Iain Marlow, Henry Meyer, Stepan Kravchenko, David Wainer and Peter Martin.

To contact the reporters on this story: Marc Champion in London at mchampion7@bloomberg.net;Ilya Arkhipov in Moscow at iarkhipov@bloomberg.net;David Tweed in Hong Kong at dtweed@bloomberg.net;Firat Kozok in Ankara at fkozok@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Rosalind Mathieson at rmathieson3@bloomberg.net, Rodney Jefferson

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.