Erdogan’s War on Interest Rates Is Making Turkey’s Rich Richer

Erdogan’s War on Interest Rates Is Making Turkey’s Rich Richer

(Bloomberg) -- President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s battle for lower interest rates risks sharpening inequalities in Turkey’s booming economy and hurting his working-class supporters.

While governments elsewhere look to curb surging prices as the global economy recovers from the pandemic, Erdogan’s betting that lower rates will turbo-boost growth and revive his flagging popularity ahead of 2023 elections.

From exporters to property tycoons, those already doing well are cashing in as borrowing costs drop and the lira weakens, but runaway food inflation and skyrocketing rents are squeezing those at the bottom -- Erdogan’s traditional base.

Driving credit-fueled growth the year before an election has worked for Erdogan in the past but the accumulating impact of that policy over the years, plus the damage wrought by Covid, means the potential social costs are much bigger this time.

Nowhere is the divergence clearer than in Istanbul’s property market, where investors are taking advantage of cheap lending to snap up real estate as a hedge against lira volatility.

In Istanbul’s once-sleepy suburb of Gokturk, gated compounds where expansive villas sell for over $1 million, are closing in on clusters of makeshift homes built decades ago by poor families on unclaimed land. New developments are sprouting up all the way to the nearby lake and forest as property prices in Turkey’s commercial capital soar.

The leafy neighborhood is now filled with trendy restaurants serving an increasingly affluent demographic while the original residents struggle to heat tiny homes as the cost of wood has nearly doubled in the past year. Some have been forced to abandon their houses and move further out after developers bought the land on which they’d been squatting.

Housing insecurity is emerging as a major social issue, with home prices in Turkey rising 13.2% as of the third quarter, the most in Europe, according to a KPMG report released last month.

Overall poverty reached its highest level in nearly a decade last year, with the Covid-19 pandemic pushing 1.6 million people below the World Bank’s threshold of $5.5 per person, per day, as wages failed to keep up with rising prices.

Hacer Foggo, founder of the Deep Poverty Network, an organization that helps low-income people, said poverty had worsened at an alarming rate, with a growing number of households failing to meet basic needs such as food and housing.

“I’ve been working in the field for the last 20 years,” said Foggo, “and for the first time I am seeing poverty turning into hunger and people asking for food.”

Yet it’s Erdogan’s push to boost growth and revive his appeal among voters ahead of the 2023 election that’s exacerbating the very imbalances that threaten to undo him at the ballot box, say economists.

The lira, which depreciated 20% against the dollar in 2020, is set for its ninth consecutive annual decline this year. It regained its title as the worst-performing emerging-market currency of 2021 after the central bank began a cycle of steep rate cuts in September. Consumer inflation accelerated for a fifth straight month in October, nearing 20%, due to a surge in energy costs and a weaker lira.

Even as markets brace for the U.S. Federal Reserve to begin tapering pandemic stimulus and most monetary authorities prepare to tighten policy, Governor Sahap Kavcioglu has signaled more interest-rate cuts to come, driven by Erdogan’s unorthodox assertion that it is high rates that are stoking inflation.

By some counts, the policy is a roaring success.

Manufacturers and exporters are thriving as the currency’s slide has sharply reduced labor costs at home and made Turkish products more competitive abroad, while cheaper borrowing has allowed companies to rapidly ramp up output since the pandemic. With growth in gross domestic product seen averaging 8.9% for 2021, the economy is growing faster than most peers. Exports are projected to exceed $200 billion for the first time in nation’s history this year.

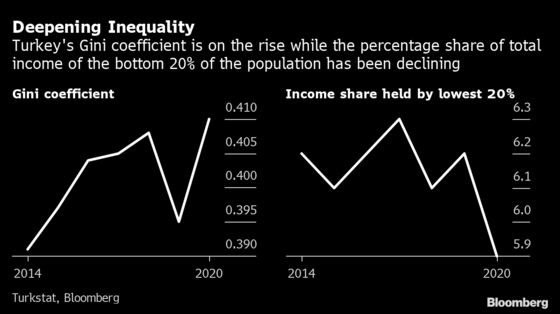

All that has come at the expense of of workers, however, as income distribution becomes more unequal. The lowest earners saw their share of GDP fall by 0.3 points to 5.9% last year, while the highest income segment increased its share by 1.2% to 47.5%, according to official data.

Rising inequality is especially hitting younger people, with youth unemployment trending at above 20%, nearly double the headline figure.

“Credit-boom driven growth is problematic. It’s overheating the economy, fueling inflation and pressuring the currency and it fails to attract high-quality resources that are required to improve welfare,” said Guldem Atabay, an economist at Istanbul-based Global Source Partners. “Deterioration in income distribution and bad governance will have a political cost.”

It’s a risk Erdogan knows too well. He began his career in the 1990s as mayor of Istanbul, building his base among working-class city-dwellers by developing infrastructure and extending social support. For two decades, the AK Party presided over a Turkey on the rise. The economy entered a decade of near-uninterrupted expansion in 2009 that transformed Turkey into a major emerging market and manufacturing powerhouse.

The past few years have been more turbulent. The pandemic struck on the heels of the 2019 recession, which partly cost the AKP control of the major cities. Pollsters say support for both Erdogan and his party are at historic lows though no strong rival has emerged.

As he tries to recreate the boom years, however, Erdogan’s pulling Turks in different directions.

In Sultanbeyli, a landlocked district on the more conservative Asian side of Istanbul where some 70% voted for the AKP’s alliance in the last general election, the appeal hasn’t ebbed.

“I’m aware of the problems in the economy but trust me, I’m old enough to remember the times when Leftists were in power,” said a shopkeeper who gave his name as Yusuf. “There’s still no better candidate than Erdogan.”

His nephew, a 23-year-old with a vocational qualification, is helping out at the shop while he looks for a job in his field.

“My uncle’s generation was lucky enough to amass a fortune during the good years of Erdogan,” he said, ignoring his uncle’s angry hand gestures. “But my generation’s becoming a lost generation because of his recent bad policies.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.