Trump’s Trade War Is Making Russia and China Comrades Again

Facing U.S. sanctions and tariffs, Moscow and Beijing are finding lots of common ground.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Fu Ying recalls vividly how, as a young woman, she’d get woken by sirens in the middle of the night for drills to practice for a Soviet invasion. It was the time of China’s traumatic Cultural Revolution and, although the farm she’d been sent to was more than 200 miles from the border, the threat seemed imminent—strong enough, it turned out, to throw Maoist China into the arms of its capitalist nemesis, the U.S.

Today’s world could hardly look more different. The U.S.-China realignment that began with President Richard Nixon’s 1972 visit to Beijing has been reversed in the most consequential geopolitical shift since the fall of the Berlin Wall. China and Russia are now as close as at any time in their 400 years of shared history. The U.S., meanwhile, has targeted both countries with sanctions and China with a trade war.

“There is no sense of threat from Russia. We feel comfortable back-to-back,” says Fu, now chairwoman of the Foreign Affairs Committee of China’s National People’s Congress, over drinks in a hotel bar near the Black Sea resort of Sochi, where she’s attending a conference. The two countries have settled the border dispute that produced a brief war in 1969.

She’s less sure about the U.S. In a speech last month, Vice President Mike Pence said the U.S. was responding to “Chinese aggression” with military spending and trade tariffs. Beijing, he said, was expanding at the expense of others and trying to drive the U.S. from the western Pacific. That kind of talk won’t be easy to forget, even if Trump and Xi agree to a trade truce at a scheduled meeting at the end of November. “I just hope that if some people in the U.S. insist on dragging us down the hill into Thucydides’ trap, China will be smart enough not to follow,” Fu says, referring to the ancient historian’s observation that rising and established powers tend to end up at war.

Even without bloodshed, this reconfiguration of the nuclear and economic superpowers is significant. Chinese investment and energy purchases make it easier for Russia to resist economic pressure over Ukraine; Russian sales of oil, missile defense systems, and jets are changing U.S. calculations in the Pacific by raising the potential cost of any future showdown with China.

Coordination in the United Nations Security Council allows the two Eurasian powers to frustrate U.S. goals and support each other’s. Nor is the U.S. the only one affected. India, which for decades relied on Russia to help balance China and Pakistan, is deeply concerned that Moscow is falling under Beijing’s sway. Russia already supplies the engines for Chinese-Pakistani fighter jets. “India needs a reconciliation between the West and Russia” to squeeze China’s strategic space, says C. Raja Mohan, director of the Institute of South Asian Studies at the National University of Singapore.

Western analysts and leaders for a long time dismissed the Sino-Russian rapprochement and its trappings—such as the NATO-lite Shanghai Cooperation Organization—as a “marriage of convenience,” doomed to fail by geography, history, and a growing disparity in strength. And the economic relationship still lags far behind the political rhetoric.

But complacency has given way to alarm. A recent study by the National Bureau of Asian Research, a Seattle-based think tank, debated whether U.S. policy was at fault for driving Russia and China together and asked if the U.S. should correct course by accommodating one Eurasian giant to isolate the other. Some among the 100-plus participants called for Washington to prepare for the worst-case scenario the realignment implies: a two-front war.

Robert Sutter, the study’s principal investigator, said at an October panel to discuss the findings that he’s had a big change of heart since he wrote in a U.S. government National Intelligence Estimate that the Russia-China relationship was an axis of convenience. “The situation is pretty bleak for the United States,” Sutter said. “And there is no easy way to fix it.”

“We are bound to step on each other’s toes around the world,” former U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger said of the U.S. and China at Bloomberg’s New Economy Forum in Singapore, on Nov. 6. He warned that a world order “defined by continuous conflict” between the two risked getting out of control, but he also said he was optimistic that could be avoided.

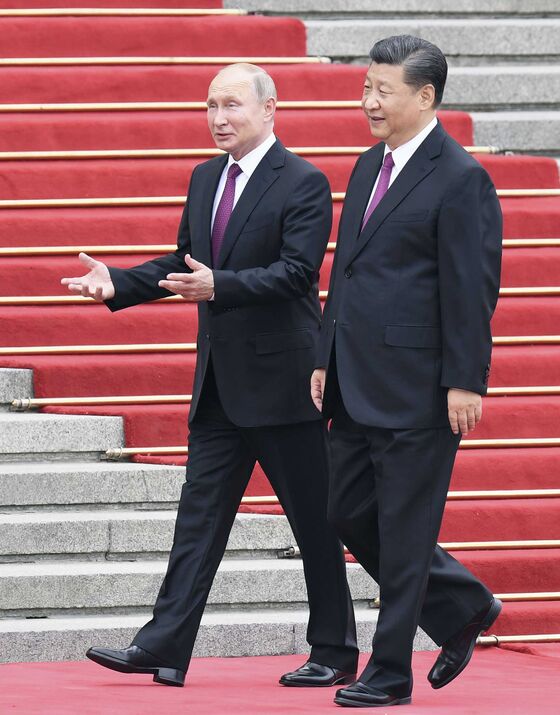

The bromance between Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping is certainly hard to miss. They meet with each other more than with any other world leaders, have awarded each other medals, and even cooked blinis and noodles together for their respective state TV channels. Joint military exercises are routine. This year, China took delivery of Russia’s most advanced S-400 air-defense system and Sukhoi SU-35 fighter aircraft, a level of trust that’s likely to thwart U.S. national security adviser John Bolton’s recent attempt to convince Moscow it faces a security threat from the East.

China has become Russia’s biggest single trade partner, even if it remains far behind the European Union as a bloc. Russia displaced Saudi Arabia as China’s top supplier of crude oil in 2015. A new pipeline, Power of Siberia, is due to start delivering as much as 38 billion cubic meters (1.3 trillion cubic feet) of natural gas per year to northern China in December 2019. Chinese entities own 30 percent of Russia’s new Yamal liquefied natural gas project in the Arctic. Russia and China have nonconflicting security concerns—in the Pacific for China and in the former Soviet bloc and Middle East for Russia. At the same time they perceive a common threat (the U.S.) and a shared goal of changing what both see as an American-dominated global order.

Their economies also are complementary: China is the world’s biggest manufacturer, and Russia is among the largest exporters of energy and raw materials. China has a shortage of arable land, and Russia a surfeit. Even their demography offers opportunities. China has a majority of men, whereas Russia has the opposite. “I could see that there are many more men in China, and people started to ask me if I could help them to find women,” says Pavel Stepanets, who started a Beijing-based matchmaking service, Meilishka, six months ago. The company website claims to have 244 “Slav girls looking for a Chinese husband.”

Russian analysts and officials say they aren’t pivoting east as much as they’re diversifying their economic and security relationships. Europe and China “are two independent destinations and two independent routes” for gas and oil, Russian Energy Minister Alexander Novak said in an October interview. “We do not see any need to redirect volumes.”

What the new eastbound pipelines will do, according to Vasily Kashin, a senior research fellow at Moscow’s Higher School of Economics, is to make Russia about 60 percent—down from 90 percent—dependent on European markets. They’ll also make China less vulnerable to a potential U.S. sea blockade should there be conflict over Taiwan. “Every pipeline project is negotiated for a decade and then built for a decade,” Kashin says. “But once it’s completed, you have an irreversible geopolitical change.”

The new geopolitical infrastructure is slowly falling into place. In January, Russia doubled its capacity to pipe crude oil to China, to about 600,000 barrels per day. In addition to the Power of Siberia project, negotiations to build two other natural gas pipelines connecting China to Siberian fields are advancing well, Novak says.

The reconciliation began with the last Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev. Even so, U.S. and Western policies since 2014 have done a lot to accelerate the Russian-Chinese rapprochement, according to Angela Stent, director of Georgetown University’s Center for Eurasian, Russian & East European Studies. Take natural gas. South Stream, a pipeline project to carry 63 billion cubic meters per year from Russia to Austria, was under construction when the European Parliament voted to block it in April 2014, a month after Russia annexed Crimea. One month after that, Russia broke the deadlock in its decade-long negotiation with China to build Power of Siberia, part of a gas purchase deal valued at about $400 billion. “It would behoove the U.S. to consider how much further to go with sanctions on Russia and how far with a China trade war,” Stent says at the same conference near Sochi as Fu.

The courtship hasn’t been easy. There was deep disappointment within Russia when China didn’t immediately flood the country with investment after 2014. Instead, it appeared to take advantage of Moscow’s weak position to get cheaper gas. Nor have the reasons for skepticism about the strength and durability of the partnership disappeared. Chinese nationalists still talk about the 230,000 square miles Russia took in the 19th century under what Beijing considers unequal treaties. And Russia was at first wary of China’s “Belt and Road” initiative, which seemed to compete with its plans for a Eurasian Economic Union. Putin and Xi have parked both issues (they agreed in 2015 to coordinate their Central Asian strategies), but competition could reemerge.

Even when the two countries were allies, in the 1950s, it was an unhappy—because unequal—partnership. When Mao Zedong came to Moscow in December 1949, Stalin kept the leader of newly communist China waiting 17 days for a second meeting, to make clear who was boss. “I came here to do more than eat and shit,” Mao complained bitterly.

Today the imbalance between the two powers has been reversed. China’s economy is six to eight times the size of Russia’s, depending on how it’s measured. “I don’t think a lot is happening” in terms of Chinese business investment, says Bruno Maçães, a senior fellow at Beijing’s Renmin University, who last year spent six months crisscrossing the region’s borders for a new book, The Dawn of Eurasia. In Southeast Asia, small Chinese businesses are highly visible as well as the big state companies, but not in Russia, Maçães says. More Chinese tourists are coming to Moscow, but it’s nothing like the throngs in Paris or New York. Visiting an island in the Amur River, which the governments have touted as a tourism zone, he found “a world from 40 years ago. To visit, I had to go through eight hours of security interviews.”

Russia’s Foreign Investment Advisory Council—chief executive officers from the 50 biggest foreign companies invested in Russia, who meet annually with Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev—still has no member from China, says Alexander Ivlev, Ernst & Young LLP’s managing partner for Russia, who coordinates the event. Still, he rattles off a list of projects Putin and Xi have signed and sees his business’s future increasingly tied to China.

Measuring the true scope of Chinese investment in Russia isn’t easy. According to Russia’s central bank, the total as of December 2017 was only $4.5 billion, a misleading figure. (Cyprus, an offshore conduit for investment from around the world, had invested $175 billion.) In a February search of an Interfax database, Kashin found 5,868 companies with Chinese equity operating in Russia, registered everywhere from Moscow to Vladivostok. That’s a higher number than for German companies (although those tend to be bigger and better established).

It may be that the Chinese are coming but are held back by the same adverse conditions deterring other investors: a sluggish economy, a weak currency, sanctions risk, and tight monetary policies that have dried up credit. That was the experience of Yema Group Co., a trading company in Xinjiang province. It set up operations in Russia in 2012 to break into the market for heavy construction machinery, dominated by more expensive European suppliers. Initially, Yema sold about 500 excavators, trucks, and other pieces a year, says Du Xuemei, a spokeswoman. “We withdrew most of our operations team in 2016, because of an economic downturn and the depreciation of the ruble,” says Du, adding that the company wants to return.

Back in Sochi, Fu draws a series of triangles on a piece of paper to show how the relationship between Russia, China, and the U.S. has changed. “This one is going to be shorter and shorter,” she says, running her pen over the line connecting Russia to China. It’s a friendship that wasn’t caused by the U.S., isn’t aimed at it, and won’t end if the U.S. alters its policies, she says. Then the Chinese legislator marks the ever more distant locations for the triangle’s American apex. “The U.S. can be here, here, or here,” she says. “It’s your choice.” —With Peter Martin, Dandan Li, and Annmarie Hordern

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Howard Chua-Eoan at hchuaeoan@bloomberg.net, Eric Gelman

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.